This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cohabitation and Conflicting Politics in French Policymaking

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This study departs from traditional interpretations of cohabitation in French politics, which suggest French institutions are capable of coping when the President and Prime Minister originate from different political parties. Instead, it offers the opposite view that cohabitation leads to partisan conflict and inertia in the policy-making process.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Cohabitation and Conflicting Politics in French Policymaking by S. Lazardeux in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Cohabitation and Policymaking in Semi-Presidential Systems

1.1 Political systems and policymaking efficiency

The capacity of political systems to promote policymaking efficiency is an essential question in democratic polities. By policymaking efficiency, I mean the ability of a legitimately elected government to enact important and needed reforms without undue obstructions from the minority. Obviously, the role and impact of the opposition on policymaking remains a matter for discussion, especially regarding what “undue obstructions” are. Should the minority be shunned from the policy process completely? Should it be able to block legislation engaged by the government, even if it is supported by an extreme majority of the citizenry? The perception of policymaking efficiency developed here stands equally apart from both propositions. It considers that the minority has a role to play in policymaking; but it also recognizes that the government should be able to take minority inputs into consideration while being able to govern following the electoral mandate it received.

1.1.1 Presidentialism versus parliamentarism

When discussing this topic, countries with radically different systems come to mind. On the one hand, the British Westminster model is efficient in translating electoral support for a program into legislation; on the other hand, it gives little opportunities to the minority in parliament to participate in the crafting of policies (King, 1976, pp. 17–18). Conversely, the American presidential system gives the opposition (notably through a strict separation of power and the senatorial filibuster) institutional means to impact the policymaking process. At the same time, these institutional dispositions are said to promote legislative gridlock (Binder, 2003).

What system, parliamentary or presidential, is best in providing policymaking efficiency? This question has been a matter of debate for decades. Disagreements among political scientists date back to the Price– Laski debate (Price, 1943; Laski, 1944; Price, 1944). At the core of the disagreement between the two authors was the question of what system was best to meet “the needs of the hour” (Price, 1943, p. 317), meaning the pursuit of the World War II and the building of a postwar society. Yet, despite their divergence, the two arguments are surprisingly concordant regarding parliamentary efficiency. Price described the British system as a system that disregards legislators in the policy process:

Once the Prime minister is in office, with the cabinet that he selects, the House remains in session to enact the bills proposed by the Cabinet, to vote the funds requested by the Cabinet, and to serve as the place where Cabinet ministers make speeches for the newspaper to report to the public (1943, p. 319)

Harold Laski, for his part, made this unequivocal statement in line with Price: “The function of a parliamentary system is not to legislate” (1944, p. 347). Hence for both authors, the British system, marked by executive dominance, proved extremely efficient.

Interestingly, more than 40 years later, Linz’ famous alert about “The Perils of Presidentialism” (1990) took up the debate where it was left off. Even though Linz primarily aimed at pointing out the danger of presidential institutions for democratic survival, he highlighted issues relevant for policymaking efficiency. Most notably, the author pointed to the presidential peril of rash implementation of policy initiatives during the president’s last term in office. On this issue, Linz declared:

A president who is desperate to build his Brasilia or implement his program of nationalization or land reform before he becomes ineligible for reelection is likely to spend money unwisely or risk polarizing the country for the sake of seeing his agenda become reality. A prime minister who can expect his party or governing coalition to win the next round of elections is relatively free from such pressures. (p. 66)

This presumed impact of presidential and parliamentary institutions on legislative productivity stands opposite to what Laski and Price argued. Price and Laski pointed to forceful executive policymaking under parliamentary institutions; Linz saw presidential executives as nothing short of dictatorial policymakers. Despite these differences, in each account, the two systems are gauged head-to-head, without much attention to within-system variations. This is the point made by Don Horowitz who, in response to Linz, argued that Linz constructed “an unfounded dichotomy between two systems, divorced from the electoral and other governmental institutions in which they operate” (Horowitz, 1990, p. 79).

This attention to the effect of within-system differences on policy-making efficiency has been pursued by some authors. This is notably the approach developed by Weaver and Rockman in their edited volume Do Institutions Matter? Government Capabilities in the United States and Abroad (Weaver & Rockman, 1993). The goal of the authors was to discern, using descriptive case studies, what factors promoted efficient governance. Among these factors were not only the political system (presidential or parliamentary) but also “regime types” (party system and type of government) and other variables such as the cohesion of elites, past policies, or socioeconomic conditions. The desire to move beyond the study of the effect of pure parliamentarism and pure presidentialism on governance was also the goal of Cheibub and Limongi (2002). The authors rightfully warned that “the operation of the political system cannot be entirely derived from the mode of government formation. Other provisions, constitutional or otherwise, also affect the way parliamentary and presidential democracies operate” (p. 153) and showed that essential variations within political systems impact how these systems function and how they impact governance, including legislative efficiency. Cheibub et al. (2004) also used this general approach, but treated this question statistically by looking at how political variables within presidential and parliamentary cases (such as minority or coalition governments) impacted legislative efficiency (measured as the proportion of legislative initiatives of the executive approved by the legislature).

Others have abandoned any attempt at gauging policymaking efficiency between political systems, but have rather looked at differences in efficiency within broad system types. For example, Lijphart looked at differences in government effectiveness between majoritarian and consensus democracies (Lijphart, 2012); Aleman and Calvo analyzed the legislative effectiveness of the Argentinian presidential system under several political configurations, most notably a situation of divided government (Alemán & Calvo, 2010); Martinez-Gallardo (2012) examines the effect of different political and institutional features (such as the institutional powers of the president) on cabinet stability in 12 Latin American presidential systems, noting that cabinet dissolutions have negative effects on the “effectiveness of policymaking” (p. 63). This is also the approach chosen by an impressive volume of studies on gridlock in the American presidential system. If most of the scholarly works on this subject matter in the 1980s were mostly qualitative and had a strong normative tone (Sundquist, 1988; Cutler, 1988), the literature has since expanded both empirically and theoretically. Mayhew’s Divided We Govern (1991) remains the major work on divided government and legislative stalemate not only for its counterintuitive finding (divided government has no independent effect on the production of landmark reforms) but also because it was the first to use quantitative evidence to tackle this question. At the same time, his analysis raised as many questions as it answered, especially concerning the operationalization of “important laws”: how to measure the amount of important laws enacted at a certain time? And what exactly makes a statute “important?” These questions have fed an impressive number of studies that use different models and different measurements of legislative productivity to reexamine Mayhew’s findings (Binder, 1999; Coleman, 1999; Edwards, et al., 1997; Fiorina, 1996; Heitshusen & Young, 2006; Jones, 2001; Kelly, 1993; Thorson, 1998). Hence, there has indisputably been an evolution toward more and more sophistication in the quantitative treatment of this issue. Moreover, while most of these works have adopted more of an inductive approach, the American scholarship has also produced noticeable deductive works that use formal modelling to derive testable hypotheses about the effect of divided government on policy gridlock (Cameron, 2000; Chiou & Rothenberg, 2003; Krehbiel, 1998; 1996).

As is made clear by this overview, the question of the impact of institutions on policymaking efficiency has expanded in two directions over the years. First, we went from a general reflection on the respective functioning of presidential and parliamentary institutions to more focused analyses of the impact of political systems on the specific issue of legislative efficiency. Second, studies have progressively abandoned inquiries about what political system is best to concentrate on how political and contextual variations within-system types can account for variations in policy efficiency.

1.1.2 Where are semi-presidential institutions?

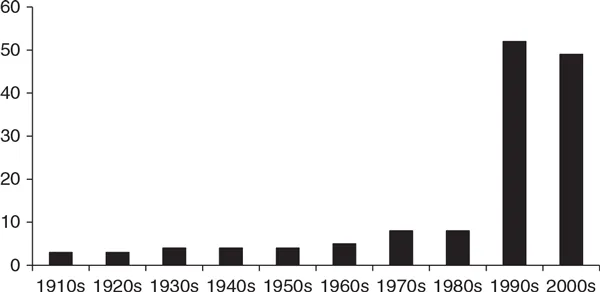

Almost a third of today’s world constitutions (see Figure 1.1) are neither presidential nor parliamentary, but are hybrids that share with presidential systems the election of the head of state by popular suffrage and with parliamentary systems the responsibility of the head of government to the legislature.

Figure 1.1 Number of semi-presidential countries by decades, 1910s to 2000s

Sources: Siaroff (2003, pp. 299–300), Elgie (1999, p. 14), and Kirschke (2007, p. 1387).

The adoption of these hybrid institutions, coined semi-presidential by Maurice Duverger (Duverger, 1978; 1980), by many former French colonies (Senegal, Burkina Faso, Algeria, or Mali, for example) and several nascent new Eastern European countries (Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine) in the early 1990s led to the integration of semi-presidential institutions into scholarly discussions on the effect of political systems on governance.

Academic attention to semi-presidentialism has since then boomed. The issue of democratic survival, the focus of Linz’s original article, was taken up by several authors who assessed the effect of semi-presidential institutions on democratic collapse (Kirschke, 2007; Linz & Arturo, 1994; Pasquino, 1997; Sartori, 1994; Skach, 2005; Protsyk, 2003). Others have looked at how semi-presidential dual executives have affected voting behavior (Gschwend & Leuffen, 2005; Lewis-Beck, 1997; Lewis-Beck & Nadeau, 2000; Magalhaes & Gomez Fortes, 2005), cabinet formation (Grossman, 2009; Amorim Neto & Strom, 2006; Protsyk, 2005; Cheibub & Chernykh, 2008; Schleiter & Morgan-Jones, 2010), or more generally intra-executive relations (Ardant & Duhamel, 1999; Cohendet, 1993; Protsyk, 2005; 2006; Zarka, 1992).

Despite the variety of substantive foci, all these studies have in common to isolate cohabitation as the dominant factor of interest in the analysis. Cohabitation simply refers to an institutional and political split executive. The institutional split is a defining characteristic of semi-presidentialism: The executive branch is represented by a popularly elected president and a prime minister, appointed by the president, but responsible to the majority in the legislature. The political split happens when the president faces a legislative majority (and consequently a prime minister) politically at odds. Based on this simple fact (a popularly elected president ideologically opposed to a popularly elected legislative chamber), it is hard not to draw a parallel between cohabitation and US-style divided government. And in fact, many scholars have made the connection between split-party governments in presidential and semi-presidential systems.1 For example, Robert Elgie noted in the introduction to the edited volume Divided Government in Comparative Perspective: “divided government does have its logical equivalent in non-presidential regimes. [ . . . ] In the case of semi-presidential regimes it corresponds to periods of ‘cohabitation’, or split-executive government” (Elgie, 2001, p. 5). This is also the point made by Shugart and Carey who argued that “where the president and the cabinet are of opposing parties or blocs, premier-presidential government faces a challenge somewhat similar to that of presidentialism under divided government” (Shugart & Carey, 1992, p. 55). 2

However, despite the clear similarities between divided government and cohabitation, and despite the scholarly interest for the issue of divided government and legislative gridlock, comparatively little attention has been paid to the effect of cohabitation on policymaking efficiency. Elgie and Moestrup noted back in 2007:

we need to assess the impact of semi-presidentialism in ways other than its effect on democratic performance. For example, it may be the case that cohabitation is not as fatal for semi-presidential regimes as has sometimes been assumed. However, it is entirely possible that cohabitation leads to less efficient decision-making, even if it does not necessarily lead to democratic collapse. At the moment, we simply do not know whether or not this is the case.

(Elgie & Moestrup, 2007, p. 248)

Two years later, Schleiter and Morgan-Jones (2009) noted the advances made in the study of semi-presidentialism, but could only find one analysis testing the effect of semi-presidential institutions on the policy process. This study, by Cheibub and Chernykh, analyzed the “batting average” of governments (in essence, the proportion of governmentsponsored bills enacted into law) in parliamentary and semi-presidential systems under different governmental configurations (minority government, coalition governments, single-party government, etc.). The authors found no systematic difference between systems, but warned that the results must be interpreted with caution, notably because they did not control for other potential determinants of legislative success (Cheibub & Chernykh, 2008). Moreover, the authors did not directly test if cohabitation had an effect on legislative stalemate.

To find elements of answer to this question, we have to dig deep into the sparse and sometimes vague literature on this topic. For example, constitutional expert Guy Carcassonne argued that French experiences of cohabitation, far from being a source of paralysis, rather served as an engine for change. He particularly noted: “qualitatively as well as quantitatively, s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Cohabitation and Policymaking in Semi-Presidential Systems

- 2. Policymaking under Cohabitation

- 3. Institutional Dynamics and Policymaking Efficiency

- 4. Cohabitation and Policymaking Efficiency: An Empirical Test

- 5. Cohabitation and Prime Ministerial Policymaking Strategies

- 6. Conclusion: Cohabitation and Policymaking in Comparative Context

- Annex: List of Major Laws Enacted per Year, 1967–2007

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index