This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

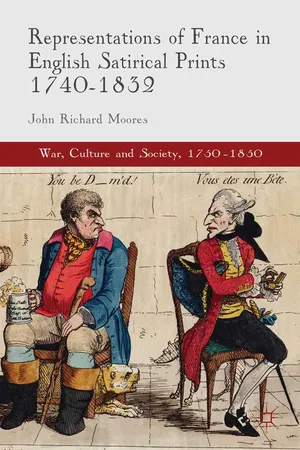

Representations of France in English Satirical Prints 1740-1832

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Between 1740 and 1832, England witnessed what has been called its 'golden age of caricature', coinciding with intense rivalry and with war with France. This book shows how Georgian satirical prints reveal attitudes towards the French 'Other' that were far more complex, ambivalent, empathetic and multifaceted than has previously been recognised.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Representations of France in English Satirical Prints 1740-1832 by J. Moores in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Studying Satirical Prints

With little consensus or consistency, historians and art historians have applied a variety of terms to the eclectic genre that is labelled ‘cartoons’, ‘caricatures’, ‘political prints’, ‘satirical prints’ and more. Sometimes these labels are arbitrarily interchanged, while single terms such as ‘caricature’ are employed to refer to widely disparate visual forms. E.E.C. Nicholson has argued that both habits impede the establishment of a ‘sensitive and viable methodology’ for handling such sources, obscuring their ‘historical specificity’.1

Recently, the application of the word ‘cartoon’ in reference to images created earlier than the mid-nineteenth century has come under fire. For Nicholson, that term is wholly inappropriate for seventeenth- and eighteenth-century prints. She sees no excuse for its utilisation at the scholarly level, even when acknowledged as an anachronism, and insists that its appearance in works ‘with any pretensions to seriousness’ be contested.2 The term was coined by Punch in June 1843 in satirical reference to the fresco designs for the new Houses of Parliament exhibited in Westminster Hall. John Leech’s ‘Cartoon no. 1’ followed on 15 July. Thereafter, ‘cartoon’ referred ‘to a genre that was blander, more speedily produced, and less ambitious’ than its Georgian predecessors. The first appearance of ‘cartoonist’ was not until 1880 and, for Vic Gatrell, connotes ‘an artist whose work was evanescent’. Eighteenth-century prints were expensive with buyers valuing them much more than modern newspaper cartoons. They were not ‘disposable fripperies’.3

Thomas Kemnitz favoured ‘cartoon’ in spite of its imprecision. Before acquiring its new meaning at the hands of Punch, ‘cartoon’ meant a preparatory sketch for a painting. Gatrell’s preferred term ‘caricature’ refers to the technique of distorting the physical features of its subject, a method often used by print artists and political cartoonists but by no means ubiquitously.4 Some critics trace the roots of caricature back to the ancient Olympians.5 The tradition of the grotesque and the mocking was maintained by, among other forms, effigies and medieval gargoyles. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) experimented with grotesque sketches, followed by Annibale Carracci (1557–1602), often hailed as the pioneer of modern caricature. Carracci developed an exaggerated form of portraiture which created a more striking image than a normal portrait by ‘loading’ the features (caricare being Italian for ‘to load’). From Carracci and his circle the technique spread across Europe, becoming popular within the aristocracies of Rome and Paris.6 In the early eighteenth century, though he personally denounced ‘caricature’, William Hogarth was producing something akin to it in his satirical moral pieces, while Italian versions were being imported to England by gentlemen returning from the Grand Tour. With progress in printing technology and growing literacy and political awareness, the form prospered in Britain, and started to be used for more political and humorous purposes.7

Unlike ‘cartoon’, the word ‘caricature’ was spoken and written by eighteenth-century contemporaries. Its usage then was also broad and arbitrary. Accompanying older terms like ‘emblematic picture’, ‘hieroglyphic prints’, ‘curious engravings’, ‘effigies’ and ‘prints’, by the 1790s ‘caricature’ could be used to describe all manner of comic, satirical or grotesque imagery.8 Yet ‘caricature’ implies physiognomic distortion, usually of an individual, given its emergence from the technique of portrait caricature. Before the 1770s and 1780s, in fact, political print artists did not tend to employ the technique of caricaturing their subjects in the sense of distorting their physiognomic features.9 Even after the 1770s, when the technique became more widespread, it was not employed unanimously. Art does not have to resort to caricature in order to be satirical.10 As well as referring to both a print medium and the artistic technique of physiognomic distortion, ‘caricature’ sometimes means ‘generic stereotype’. Its threefold definition is clearly problematic.11 ‘Satirical print’ might seem an appropriate label, but were all such prints strictly satirical? Some appear softer, less opinionated and antagonistic, than the implications of that word, and can be read as observations rather than satires as such. The term ‘satire’, writes Nicholson, should be saved for prints whose satirical objective can be persuasively verified.12 She sees ‘political prints’ as the ‘most basic and unexceptionable’ of terms, though would prefer it to apply exclusively to non-satirical prints, which she feels have been neglected by prior modes of categorisation. She also finds ‘graphic political satires’ acceptable and (only for those prints in which caricature can be said have been employed) ‘political caricatures’.13 Evidently some prints were more directly political than others and Nicholson is vaguer on those which Dorothy George deemed ‘social satires’. Brushing over the differences between the political and the social, Nicholson would like to see the term ‘social caricature’ ascribed to designs in which ‘specific individuals are known to have been intended, as well as where the treatment of the subject represents merely the application of caricature to stock comic genre scenes’. The term ‘social satires’, meanwhile, should be restricted to those ‘which register more bite, and in which humorous observation is subordinate to implicit criticism’.14 Nicholson does not specify how we might define or measure this ‘bite’ or the differences between implicit and explicit criticism. The consensus of terminology envisaged by Nicholson has yet to materialise. She has not entirely solved the problems of print terminology, with her proposed alternatives offering their own difficulties. Still, Nicholson has shown that scholars could be more careful, specific and consistent than they have been regarding the labels they apply, when they apply them and why. It is not the purpose of this volume to make bold new strides in the terminological methodology of print studies. As the material studied here is principally that which focuses on and satirises France and Anglo–French relations, terms such as ‘political prints’, ‘satirical prints’ and ‘graphic satires’ have been deemed suitable. Care has been taken not to label something a ‘caricature’ where no technical caricaturing is apparent.

Contentious terminology aside, why study this material? One answer, and one that few historians who work on visual prints fail to mention, is simply that they have been understudied and underused.15 Their neglect does not automatically justify their study. Have they been disregarded because they are of little use? Although they refer regularly to newspapers, surviving eighteenth-century texts rarely mention prints, which might suggest prints’ cultural irrelevance.16 This misleading scarcity of primary commentary makes the study of prints difficult. Prints were neglected by some contemporary writers because of their status in society. People who enjoyed prints might not have wished to write or talk about them because of the negative connotations of crude imagery and laughter which were pertinent in mannered society. Not all prints were humorous, but many were, and laughter could be considered unseemly, impolite, uncivil and characteristic of the lower orders.17 Because of their appearance, their sketch-like quality, their vividness, their frequent rudeness and crudity, they were considered ‘low-art’ and would have suffered from all the implications of this, including the wish of the respectable to enjoy prints privately. Yet people did enjoy them, as proven by the vast numbers produced, sold, and surviving, the crowds that were said to congregate outside printshops, and the large collections that individuals accumulated. As Gatrell maintains, ‘scarcity of comment is no index of a commodity’s cultural consequence’.18 Mark Hallett, meanwhile, argues that the quantity of their detailed advertisements tells us that satire was ‘highly visible’ and ‘highly marketed’.19

There is debate over who exactly saw the prints. Costs varied, but in the earlier years of the century the standard price was 6d for a plain print and 1s for coloured. By 1800 this had doubled to 1s plain, 2s coloured, with many of James Gillray’s larger coloured prints over 3s.20 The print-buying audience expanded over the course of the eighteenth century to include portions of the middle classes, so caricature did not remain an exclusively elite, aristocratic genre.21 Still, they were too expensive for most people’s means.

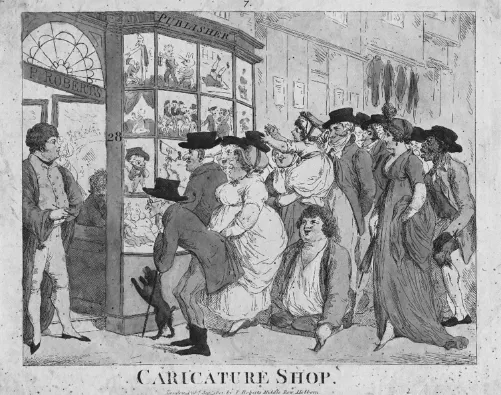

There were other ways for poorer people to access the designs, although scholars cannot agree on the extent to which the popular classes might have been exposed to them. Bound volumes of prints were available to rent. This, too, was expensive. In the 1790s the printseller Samuel Fores was charging a half-crown rental fee per night, with a one pound deposit.22 Towards the end of the century, sellers like Fores and William Holland hosted print exhibitions charging an entrance fee of one shilling, but this too was beyond most people’s reach.23 Cindy McCreery speculates that London apprentices, sailors or tavern customers clubbed together to purchase prints for display in communal areas (their workshop, communal residence or tavern) in the same way that groups shared ownership of periodicals and books.24 Gratis exhibitions could be enjoyed by gazing into the windows of the printshops where the latest designs were displayed. One French visitor complained that the crowds grew so large that ‘You have to fight your way in with your fists’ and in 1819 the authorities were forced to clear the street outside William Hone’s shop after George Cruikshank’s Bank Restriction Note attracted such an excessive crowd.25 A small number of prints themselves depict the phenomenon of crowding outside windows, highlighting not only the size but the diversity of the crowd. These include the anonymous Caricature Shop [LW 801.09.00.01] of 1801, showing the exterior of Piercy Roberts’s shop. Roberts’s crowd includes well-dressed ladies and gentlemen as well as a hunched old man, a young child, a black man, a beggar with no legs and even a small dog (Fig. 1.1). Gillray’s Very Slippy-weather [BMC 11100] (1808), featuring the exterior of Hannah Humphrey’s shop, also shows the printshop window’s function as ‘a free gallery for the poor’.26

Figure 1.1 Caricature Shop (1801). Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

The images were not available in one format exclusively. Designs could appear on early forms of the postcard, medals, coins, ladies’ fans, handkerchiefs, playing cards and decorative screens, as illustrations in books, on penny ballads, in broadsides or other publications, and on ceramics.27 Cheaper, bootleg copies of designs by the likes of Gillray (the era’s most pirated print-maker) were available to wider audiences.28 Pubs and similar establishments sometimes had prints decorating their walls.29 These formats extended the audience beyond those with access to printshops.

For Nicholson, windows and reproductions do not equal popularity.30 The image may be more universal than the printed word, but Nicholson believes that even if the poorer classes were able to access such works they would not be able to understand them because the pictures were intended explicitly for consumption by wealthy, educated buyers and thus had no incentive to make concessions to a popular audience. Many included lots of text, often employing French and Latin phrases, and most featured what Nicholson considers ‘allusive iconography’.31 H.T. Dickinson resolved that most prints were not perused by the lower orders because many included writing and ‘most political prints assumed a high level of political intelligence and knowledge’.32

Accepting that we have no precise literacy figures for the era, T.L. Hunt disputes the attitude of Nicholson and Dickinson by quoting a foreign visitor to England in the mid-eighteenth century (‘Workmen habitually begin the day by going to coffee-rooms in order to read the daily news. I have often seen shoeblacks and other persons of that class club together to purchase a farthing paper’). Hunt references varying estimates of rudimentary literacy, none of which, she asserts, dismisses the working class as totally illiterate, and cites the political deb...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Series Preface

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on the Images

- 1 Studying Satirical Prints

- 2 Food, Fashion and the French

- 3 Kings and Leaders

- 4 War (and Peace)

- 5 Revolution

- 6 Women and Other ‘Others’

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index