eBook - ePub

The Charismatic City and the Public Resurgence of Religion

A Pentecostal Social Ethics of Cosmopolitan Urban Life

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Charismatic City and the Public Resurgence of Religion

A Pentecostal Social Ethics of Cosmopolitan Urban Life

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Two powerful and interrelated transnational cultural expressions mark our epoch, Charismatic spirituality and global city. This book demonstrates how these two forces can be used to inform ethical design of cities and their common social lives to best support human flourishing, spirituality, and social and ecological wellbeing of their residents.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Charismatic City and the Public Resurgence of Religion by N. Wariboko in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Ethics & Moral Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Ethics & Moral Philosophy1

THE CHARISMATIC CITY

RELIGIOUS SENSE AND SENSIBILITY FOR FUTURE URBAN DESIGN

INTRODUCTION

There is now a global articulation of cities or segments of cities in a worldwide network society or agglomeration. This new creation does not refer to any one metropolis or place, but to interactive networks of places and connectivities in communications, transportation, and their relationships. Some have called these transterritorial networks the “global city,” the “world city,” the “New Creation,” or the “urban cosmopolitan civilization.” We will call it the “Charismatic City.” This name is selected to mark a fresh conception of the future city in five distinct, but related, ways.

First, we conceive the global city as an emerging New Jerusalem, a site of a more intense participation in God’s presence. It is a space for the work of the Spirit, a site of transimmanence. The Spirit is involved in the gritty materiality of human sociality, animating and reanimating it to exhibit charis (gifts) and charisma, and to manifest and actualize maximum goodness. The idea of the world city as the New Jerusalem calls for a different starting point for inquiry into the sociohistorical analysis of the formation of the cosmopolitan urban reality.

Second, we situate the global city as imbricated with the contemporary explosion of energy flows, a phenomenon of our epoch. We are in an era governed by the worship of bold, rapid, abundant energies. From gushing oil wells to chain reactions of atomic explosions, from race cars to space shuttles, from action movies to bungee jumping, from supersonic chats of cell-phone text messaging to the profoundly instantaneous and infinite speed of the Internet, everything is in a mode of explosion and detonation. As Peter Sloterdijk puts it, we are all “fanatical adherents of explosions, worshippers of that rapid release of a large quantity of energy.”1 The formation of the world city is affected and permeated by supranational or global spiritual (religious, emotional) energies. Pentecostalism (in its fury, exuberant energy, and rapid growth) is the religious archetype of the impetus of our age. Pentecostal-charismatic movements, with their intense, exploding spiritual energies that are not only transterritorial, but also work and prosper through the same transport and communications technologies, condition the ethos of the world city. But scholars have often ignored these movements in the analysis of the future city. This chapter gives prominence to Pentecostal sensibilities in our thinking about the ethics of the emerging global civil society.

Third, we have named the future city the “Charismatic City” in order to highlight the need for a design of cities that will better promote or maximize (good) emotional energy in the interaction ritual chains that structure and destructure cities as the “space of flows and the space of places.”2 What I am suggesting here is the need for urban designers to pay attention to the kinds of interactional situations among a city’s populace that enable the city to acquire emotional significance. Or even to become “charismatic” in the Durkheimian sense—a symbolic repository of a people’s emotional energies. What mechanisms can be built into a city’s life to produce and promote awe or moral solidarity, to hold it together? Following Emile Durkheim and sociologist Randall Collins, we argue that we do so by focusing, intensifying, and transforming emotions.3 A city is a multiplicity of emotional patterns of social interactions. We maximize the feeling of psychological well-being and solidarity of a city’s interactional situations if there are sites or opportunities for mutual focus of attention to occur and emotional entrainment to build up among its dwellers and visitors. “Where mutual focus and entrainment becomes intense, self-reinforcing feedback processes generate moments of compelling emotional experience. These in turn become motivational magnets and moments of cultural significance.”4

A well-designed city is like a successful social ritual that enables its participants to feel strong, secure, hopeful, and either motivated to initiate something new or, at least, to take the initiative to do so. The secret of a successful social ritual, according to Durkheim, is the generation of high emotional energy and being an emotional transformer.5 We have often designed cities for economic efficiency (cost/time reduction and maximization of economic gains). But this type of cost-benefit analysis ignores the benefits of the emotional payoff of participation and interaction in the city. Collins argues that “humans are not very good at calculating costs and benefits, but they feel their way toward goals because they can judge everything subconsciously by its contribution to a fundamental motive: seeking maximal emotional energy in interaction rituals.”6

Fourth, by conceptualizing the city as chains of interaction rituals and a place traversed by strong flows of energy, we open a path to interpret it as a real virtuality (Gilles Deleuze’s term) and as a plastic organ (in Catherine Malabou’s sense).7 Building on Deleuze’s insights in Difference and Repetition, we argue that the city is not a mere container or inert receptacle in which people live and act, but it is a kind of noumenal machinery behind the millions of interactional situations or phenomena. The city is real virtuality that conditions the genesis of the forms of the interactional situations. Following Malabou, we state that the city as a world of material and energetic flows engendered by millions of micro interaction rituals is characterized by plasticity. This refers to three of its properties. It possesses “at once the capacity to receive form . . . and the capacity to give form . . . But it must be remarked that plasticity is also the capacity to annihilate the very form it is able to receive or create.”8

Finally, this chapter simultaneously revises and updates the argument of the Secular City as put forward in the 1960s by scholars such as Harvey Cox. Since God has refused to die and the divine presence has failed to deteriorate in its dispersal from sacred centers or temples as the secularists expected, how should we theologically thematize the (future) city given the upsurge of religion and spirituality in the twenty-first century? The thesis of the Charismatic City does not totally refute the key arguments of the Secular City, but takes it up and develops it in a different way based on the resurgent spirituality of today. The Charismatic City is constituted as a palimpsest—it is precipitated out of the sacred and secular cities. It is superimposed on these two forms of the city and may, therefore, in particular times, assume qualities reflective of them. The notion of the Charismatic City shifts the focus of the intent of the Secular City from Webberian rationalization and routinization to the improvisation of charisma, numinous, and awe. We want the intent of the city to be awephilic (love of awe).

THE LOGICS OF THE CHARISMATIC CITY

We will now combine these five ways of looking at the future city into a philosophical-theological framework for creating or designing a more psychologically satisfying urban experience. The inner logic of this framework is a theological interpretation of the morphology of the city. This interpretation is driven by the tension and articulation between the voluntary principle of association and the dynamic of divine presence. The voluntary principle on which the Church, ecclesia, is based calls persons out of the gene-pool identities, blood and soil, castes, races, tribes, nations, classes, and state into interactive networks that link practices, events, and people into a distinct network society. The Church is a community of voluntary persons set in between the family and the state. The idea of blood and soil, which limits identity or association to genes and land, is contrary to the logic of voluntarism. The Sacred City with its invocation of ultimacy of a place of worship or divine encounter, and its exclusivist-hierarchical claim on divine presence as a basis of identity of people or their land, is inconsistent with the principles of Christianity.

The logic of divine presence organizes the experience of human encounter with the divine along nodes or a continuum of concentration and dispersal. So, for instance, the key fundamental argument of Harvey Cox in his 1965 bestseller, The Secular City, is not so much the death of God as the movement of divine presence out of the sacred places, institutional churches, or temples, and into all places and interstices of social existence. The “Secular City” as a metaphor for the divine–human relationship emphasizes the radical immanence of God in this world such that there is no longer a religious (transcendental) determination of symbols of cultural integration. Cox uses the phrase also to refer to the process of industrialization, urbanization, and technological expansion that has disenchanted nature, deconsecrated values, and desacralized politics. Secularists also interpret the dispersal of divine presence into the world or the removal of the distinction between regular priests (in monastic orders) and secular priests (serving the world) as one of the developments that delivered men and women from the fear of freedom to assume responsibility for their world.9

The Secular City as a thematization of the secularization process in Christianity—and not secularism—is both a critique and a rejection of ecclesiastical totalitarianism and the remains of old Christendom. The notion of the Secular City as a paradigmatic form of city in the urbanization process is also a rejection of the notion of the Sacred City, as we shall demonstrate later. On the continuum or spectrum of the concentration-dispersal of divine presence, the Sacred City is at the extreme end of concentration. But in the Secular City, no one place is of ultimate power and worth. In fact, secularists maintain that God or the gods have fled the established sacred places. God may be dead in the authorized places of worship such as the temple, but is alive in the profane (world), in the decentralized nodes of religious power. Just as Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s Empire has no controlling center, the Secular City as against the Sacred City does not recognize any controlling or absolute center of God’s presence.10 For our limited purposes, this is the salvageable argument of the secular-city thesis.

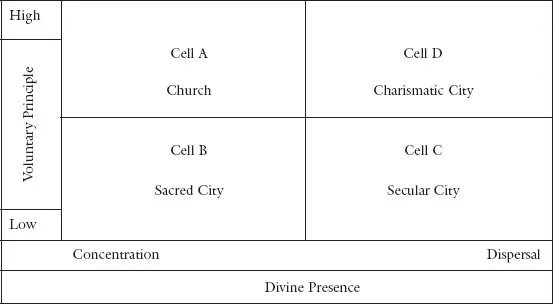

Thus our analysis of the sociohistorical evolution of the global city, New Jerusalem, or the Charismatic City is structured by the competing logics of the voluntary principle and the dynamic of divine presence. Based on these two logics, we will identify three paradigmatic cities in Christian theological–ethical thought: Sacred City, Secular City, and Charismatic City. Figure 1.1 presents this idea in a diagrammatic manner.

Figure 1.1 Sociohistorical evolution of the future city.

It is important to note that our interpretation of the sociohistorical evolution of the city does not consider the city as merely a space of residence, work, and entertainment. The city, according to Harvey Cox, is “the pattern of our life together and the symbol of our view of the world.”11 As he puts it, the Greek polis is different from the medieval city and they are both different from the Secular City because each represent different ways of living together and a different worldview. The worldview gives meaning to their people’s life together and is in turn affected by the common life they live together. Using Cox’s logic, in the era of globalization, Empire, and Internet connectivities, which is marked by profound changes in the way we visualize God and gods and the problematization of the sacred–secular divide, we are inevitably in a new type of city that has come (is coming) into being. It is this emerging new city that I have named the Charismatic City.

Let us explain what the cells in figure 1.1 mean for understanding the sociohistorical evolution of the city. We start with Cell A, the Church, as our point of departure for the dialectics of the two logics: voluntary principle and divine presence. The Church has a high voluntary principle but tilts more to the side of the concentration of divine presence. It broke with primal communitarianism as defined by fixed gene-pool identities of families, tribes, ethnic groups, race, castes, or territorial-linguistic defined identities. Ideally the Church is a symbol of transition from tribe, blood, soil, and caste to the universal community of humankind. It is a detribalizing movement marked by universality and radical openness.12 It is a new center of brotherhood and sisterhood that allows for voluntary construction of identity and personhood. The Church, ecclesia, a civil society located between the family (tribe or ethnic group) and the state, is ideally not conceived to accumulate powers to “establish a governing institution that comprehends all other institutions internal to a society in a given territory.”13

But the Church in history has not always behaved in ways that show it is not the domestic religion of any class, race, or ethnicity. So medieval Christendom, with its sacred city of Rome and the concentration of religious and political authorities at one church in one city, subjugates the ideal of the Church to tribal chauvinism and belief in the concentration of divine pr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 The Charismatic City: Religious Sense and Sensibility for Future Urban Design

- 2 The Church: Beginnings and Sources of the Charismatic City

- 3 The King’s Five Bodies: Pentecostals in the Sacred City and the Logic of Interreligious Dialogue

- 4 Fire from Heaven: Pentecostals in the Secular City

- 5 Forward Space: Architects of the Charismatic City

- 6 Pentecostals in the Inner City: Religion and the Politics of Friendship

- 7 The Communion Quotient of Cities

- 8 Religious Peacebuilding and Economic Justice in the Charismatic City

- 9 The Charismatic City as the Body of Christ

- 10 Summary and Concluding Thoughts

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index