eBook - ePub

Deepening Neoliberalism, Austerity, and Crisis

Europe's Treasure Ireland

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

From bank bailouts to austerity, Europe's and Ireland's response to the economic crisis has been engineered specifically to shift the burden of paying for the crisis onto ordinary citizens while investors, financiers, bankers and the privileged are protected. The authors expose the class-based nature of Ireland's crisis resolution.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Deepening Neoliberalism, Austerity, and Crisis by Julien Mercille,Enda Murphy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Trade & Tariffs. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

The title of this book was chosen because ‘Treasure Ireland’ is the phrase that large pharmaceutical corporations use when referring to Ireland, given the size of profits to be made in the country (Sunday Business Post, 2014). The Irish state has long adopted a subservient attitude towards corporate interests, a trend that has been intensified since 2008 when the economic crisis began. Thus, this book argues that Ireland’s political economy is best conceived as neoliberal. It presents a theoretical framework that explains our interpretation of neoliberalisation and how it has been deployed in Ireland. We focus on the current period of austerity and crisis, but trace the roots of Ireland’s neoliberal development path over the last several decades. We identify and explain the sources of neoliberalisation and maintain that they originate both in domestic socio-economic structures and from abroad, in particular, from the European Union (EU), of which Ireland has been a part since the 1970s (it joined what was then the European Economic Community in 1973). Our overarching point is that the public policy response to the ongoing economic crisis has been squarely in line with the interests of Irish and global economic and political elites. In other words, the last few years have witnessed a deepening of neoliberalism, in Ireland and Europe. Our explanation improves on Irish-centric accounts that neglect the influence of developments outside the country on domestic political economy.

By providing a systematic and historical interpretation of neoliberalism in Ireland, this book contributes to filling an important gap in the literature. There have not been many studies of the European economic crisis framing it within a critical political economy perspective, let alone interpreting it through the lens of neoliberalisation. Moreover, although Ireland has become increasingly relevant to an understanding of the crisis as a case study shedding light on Europe’s condition, a number of aspects of its political economy have yet to be fully documented. We build on the work of others who have started laying the foundations for such a project, whose writings we discuss in the following pages. We surely do not contend to have produced the definitive volume on the subject, but rather hope that the book will stimulate more research, both contemporary and historical. Indeed, there are other sectors that have also fallen victim to the processes of neoliberalisation that could have been included in this volume but are absent. These include the housing sector which has witnessed the ever more gradual removal of the state from the public provision of shelter for poorer citizens, large-scale mortgage arrears, and extensive homelessness, among other issues. Similarly, the natural resource sector is one which has been the target of private interests under neoliberalisation. Also, the education system has been subjected to cuts and universities have been aligned to a greater extent with the needs and interests of the corporate sector. In this sense then, we have aspirations that the book will act not only as as a template but also as a springboard for the pursuit of similar research in these areas.

Describing Ireland as a state that has developed in parallel with global neoliberalism since the 1970s highlights the fact that the country is, in this respect, not all that different from other Western nations. This interpretation improves on claims of Irish exceptionalism that imply that the country can hardly be compared with others. Such assertions often have the effect of upholding the status quo and rejecting criticism of enacted policies. The latter are defended under the pretext that they constitute ‘an Irish solution to an Irish problem’, and that therefore, pointing to their known negative consequences elsewhere is irrelevant. On the contrary, by placing Ireland within larger developments in the world economy and the EU, and in particular as an actor in the shift towards neoliberalism over the last several decades, it can be seen that policies that have redistributed income and power upwards to the detriment of the majority of the population in many other countries will have, and indeed have had, similar effects in Ireland.

The book also maintains that a firm grasp of politics and economics, especially during the years of crisis from which we may only slowly be emerging, comes through an understanding of power. We define power in a societal context as the ability of one individual or group of individuals (i.e., the corporate or wealthy classes) to affect public policy in a manner that disproportionately serves their own interests at the expense of the general population. The fact that a relatively small number of corporate and political elites hold a disproportionate amount of power over the majority of the population is a simple yet significant fact that is often obfuscated or neglected in scholarship and commentary. We believe that accounts that fail to recognise this reality are bound to be incomplete at best. We discuss the multiple ways in which power has operated in Ireland during the crisis and the consequences that have followed. For this task, we draw on the broad field of critical political economy; our account is solidly grounded in theoretical scholarly debates, but we have tried to minimise the use of technical jargon. For this reason, we use terms such as ‘political and economic elites’, ‘corporate elites’ and ‘ruling class’ more or less synonymously. We take this political and economic elite to mean a range of individuals and institutions including financial interests, exporters and traders, leading industrialists, large landowners, media owners, the top echelons of the military and civil service, and their political and intellectual proxies. Finally, we refer to the so-called ‘PIGS’ countries (Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain) as countries of the EU ‘periphery’ and to countries such as Germany, France, Belgium and the Netherlands as ‘core’ countries. This refers to their relative power within the EU and borrows from the literature on uneven development at a systemic scale. Core countries may be seen as the EU’s leaders and have significantly more influence on its political economy and policy-making than weaker peripheral countries (Lapavitsas et al., 2012).

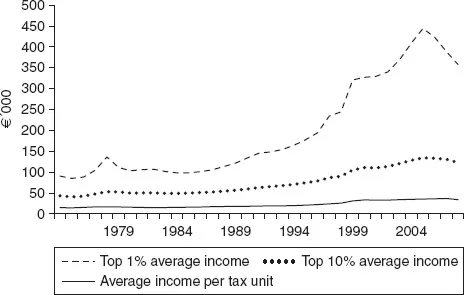

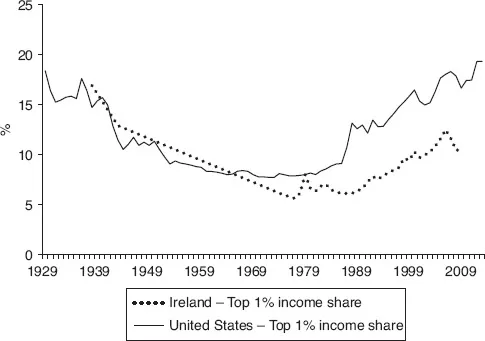

Subsequent chapters explain in detail how neoliberalism has been deepened in recent years and how elites have sought to strengthen their position relative to ordinary people in response to the economic turbulence in Europe and Ireland. The broad picture can readily be appreciated through the following three figures. Figure 1.1 shows that the top 1 per cent and top 10 per cent of incomes in Ireland have grown much more than average incomes since the 1980s. For example, between 1975 and 2007, the annual average income of those in the top 1 per cent surged from approximately €90,000 to nearly €450,000 whereas average incomes only increased from €15,000 to €35,000. Figure 1.2 shows how the trends in the share of total income captured by Ireland’s top 1 per cent income group mimics the situation in the United States, itself a very unequal country, and how it has become more unequal since the 1970s when neoliberalism began to be articulated in public policy. Moreover, between 1975 and 2009, the share of total income going to the top 10 per cent increased from 29 per cent to 36 per cent and the share going to the bottom 90 per cent dropped from 71 per cent to 64 per cent.

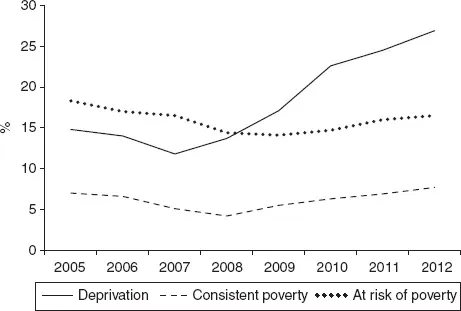

Finally, Figure 1.3 illustrates how the neoliberal response to the crisis has led to increased levels of deprivation and poverty. Indeed, at the time of writing, nearly 27 per cent of the Irish population suffers from deprivation, up from approximately 12 per cent in 2007, while poverty levels have also risen. Yet at the same time, it was recently reported that 14 of Ireland’s top companies are sitting on a €12.3 billion cash pile built up during the recession years, up from €6.4 billion in 2006 (O’Connor, 2014). Moreover, the 17 top Irish bankers are now paid on average €1.2 million each per year, a situation that reflects European trends, where 3,529 bankers are paid more than €1 million each per year (Newenham, 2013). Clearly, the crisis and austerity have had strikingly different effects on the rich and ordinary people.

Figure 1.1 The rise of the top 1 per cent and 10 per cent in Ireland, 1975–2009 (real 2010 euros ’000)

Source: The World Top Incomes Database, http://topincomes.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/#Database:

Figure 1.2 Top 1 per cent income share in Ireland and the United States, 1929–2012

Source: The World Top Incomes Database, http://topincomes.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/#Database:

Figure 1.3 Deprivation and poverty in Ireland, 2005–2012

Source: CSO (2014).

The next chapter is theoretical in nature and explains our conceptualisation of neoliberalism, which we interpret as a set of principles aiming to restore and increase the power of the corporate sector and societal elite over the majority of the population. We review our usage of the term in relation to the existing scholarly literature and discuss how our approach differs from that of others. In particular, we maintain that equating neoliberalism with the alleged prominence of the ‘free market’ and marketisation since the 1970s is incorrect or misleading. It is more accurate to define it in terms of a range of mechanisms (some market-based, others anti-market) that have resulted in increased corporate power and freedoms relative to ordinary people. Through such mechanisms, we argue that neoliberalism has been gradually deepened in Ireland since the 1970s, influenced by both national and international forces, institutions and actors. We present a theoretical framework that clarifies such factors chronologically and orientates the discussion throughout the book.

Chapter 3 provides an interpretation of the evolution of Ireland’s neoliberalisation over time. It highlights, in particular, the role of international rule regimes (such as the International Monetary Fund [IMF], World Bank, and others) in shaping and, at times, forcing neoliberal policy change through the state and its institutions. Chapter 4 discusses how the EU has become neoliberal since the 1980s, a development shaped by (transnational) industrial and financial interests and lobby groups. In particular, it maintains that post-Maastricht Europe and the single currency regime are quintessential neoliberal constructions. During the crisis, the EU has aggressively sought to deepen neoliberalism over the continent and impose it on peripheral countries facing financial difficulties and bailouts, Ireland’s having been foremost in this development.

Chapter 5 argues that neoliberalism contains an important ideological dimension that articulates a specific ‘common sense’ making neoliberal policies more acceptable to the public, even if they redistribute income and power upwards. One of the main ways in which consent is constructed is through the mass media, which we argue convey messages that reflect the viewpoints of economic and political elites promoting the interests of the holders of power and marginalising those that favour the majority of the population. The favourable ways in which news outlets have presented the government’s policy response to the crisis are investigated in order to illustrate those claims empirically. Chapter 6 discusses privatisation, a key element of neoliberalism. It shows that the response to the crisis has emphasised the transfer of public assets and service delivery to the private sector with renewed intensity, which has been supported by the EU, the IMF, and the Irish government. The discussion is framed theoretically by the concept of accumulation by dispossession.

Chapter 7 discusses the health care system and austerity’s effect on it. It shows that more of the costs of care have been shifted onto patients, and that the Irish government’s proposed reforms benefit health insurance companies rather than the users of health care. A broader point is made about the social determinants of health, namely, that poorer segments of the population have worse health than the better off. Therefore, a strategy of austerity that negatively affects the poor and vulnerable undermines any pretence of progressive health care reform. Chapter 8 focuses on labour. It outlines the extent to which neoliberal logic has played out under labour market reform. Labour has been attacked and subdued under government-led post-crash resolution policies where pay and working conditions have been eroded in an attempt to discipline workers. At the same time, the chapter also argues that unemployed labour has also been targeted through the welfare system where increasingly hostile ‘workfare’ arrangements have been introduced under labour market ‘activation’ policies. Chapter 9 discusses the Irish taxation system. It argues that under neoliberalisation, the system has been gradually reconfigured to favour capital over ordinary citizens. We contend that Ireland is a tax haven that functions as an important element in the global system of corporate tax avoidance. This, together with low headline rates, has resulted in capital being taxed at a very low effective rate. At the same time, the general taxation system has placed an increasing burden on ordinary people, exacerbating income inequality.

2

Neoliberalism, a Class Project

Capitalism with the gloves off

Neoliberalism has become a relatively popular concept in critical scholarship, having been used in a variety of contexts while taking on a range of meanings (Boas and Gans-Morse, 2009; for surveys, see Saad-Filho and Johnston, 2005b; Roy et al., 2006; Steger and Roy, 2010). In this book, the word is used to refer to a set of ideas and practices whose objective is to restore, increase and maintain the power of economic elites relative to ordinary people. It is a class project that has developed as a response to the erosion of the corporate sector’s economic power during capitalism’s ‘golden age’ that lasted from the end of World War II until the late 1960s (Harvey, 2005a; Duménil and Lévy, 2004, 2011).

Neoliberalism has spread in advanced and emerging economies to varying degrees since the 1970s and is characterised by market deregulation, monetarism, privatisation, the weakening of labour’s bargaining position and working conditions and attacks on the welfare state. It has also been marked by the financialisation of Western economies and the relocation of manufacturing to Asia and elsewhere to capture cheaper labour pools and cut production costs. Consequently, economic growth has come to depend to a larger extent on credit and debt accumulation (corporate, personal, governmental), given the deindustrialisation of the West and the stagnation of real wages during the last several decades (Lapavitsas, 2013b; Magdoff and Foster, 2009). Neoliberalism has imposed itself gradually by shifting ideological discourses and common sense towards a greater popular acceptance of values of competition and marketisation but also violently and through ‘shock therapy’, affecting negatively the lives of countless individuals worldwide (Klein, 2008; Mirowski and Plehwe, 2009).

Moreover, neoliberalism implies a ‘democratic deficit’ in political and economic governance (Gill, 1998a; Chomsky, 1999). This goes hand in hand with the increased power and freedoms of business and the retrenchment of government from various areas of economic and political life, most directly through privatisation. In principle, this means a reduction of democratic input into policy-making as decisions are relegated to private institutions that are unaccountable to the public. This makes sense for elites as neoliberalism’s objective is to strengthen and solidify their privileges. It is a project of a minority against the majority, but nevertheless gathers a range of individuals and institutions in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Neoliberalism, a Class Project

- 3 Encountering Neoliberalism

- 4 European Rule Regimes and Deepening Neoliberalism

- 5 Ideological Power and the Response to the Crash

- 6 Privatisation

- 7 Health and Health Care

- 8 ‘Austere’ Labour

- 9 Taxation: Redistribution Upwards

- 10 Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index