This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Neuroscience and the Future of Chemical-Biological Weapons

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

During the last century, advances in the life sciences were used in the development of biological and chemical weapons in large-scale state offensive programmes, many of which targeted the nervous system. This study questions whether the development of novel biological and chemical neuroweapons can be prevented as neuroscience progresses.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Neuroscience and the Future of Chemical-Biological Weapons by Malcolm Dando in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Military Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Past

1

Neuroscience and CBW

Introduction

States are unlikely to spend the time and effort required to negotiate and implement international multilateral arms control and disarmament agreements unless there are serious problems that require the use of such complex methods. Multilateral negotiations can take years to conclude, resulting in the need for extensive national implementation and ongoing multilateral engagement in order to assess the operation of the agreement and how it might need further elaboration.

Therefore, the fact that over the last century three such international multilateral agreements were negotiated and implemented in relation to the control of chemical and biological weapons leaves little doubt that many states perceived that such weapons were a significant threat. During the terrible war-torn twentieth century1 the 1925 Geneva Protocol, the 1975 Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) and the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) progressively brought tighter and tighter control over the proliferation of these weapons.

The 1925 Geneva Protocol was negotiated following the large-scale use of chemical weapons, and the initial crude attempts to use (anti-animal) biological weapons,2 during the First World War. Now that most of the many reservations that were lodged at the time have been removed, the Protocol bans the use of chemical and biological weapons.3 In 2012 the United Nations General Assembly once again reaffirmed the ‘vital necessity’ that states uphold the provisions of the Protocol and called upon States still holding reservations to withdraw them.4

The Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention was opened for signature in 1972 and entered into force in 1975. Its first article adds a series of further prohibitions to the ban on use stating, in part, that:5

Each State Party to this Convention undertakes never in any circumstances to develop, produce, stockpile or otherwise acquire or retain:

1. Microbial or other biological agents, or toxins whatever their origin or method of production, of types and in quantities that have no justification for prophylactic, protective or other peaceful purposes.

Thus, under what has become known as the General Purpose Criterion any peaceful uses of biological and toxin agents are allowed but non-peaceful purposes are banned. Like the 1925 Geneva Protocol, the BTWC continues to be developed through its five-yearly Review Conferences, the latest of which took place in 2011.6

Whilst Article IX7 of the BTWC recognised the ‘objective of effective prohibition of chemical weapons’ and states party to it undertook ‘to continue negotiations in good faith with a view to reaching early agreement’, it was not until the end of the East-West Cold War that the Chemical Weapons Convention was agreed. It opened for signature in 1993 and entered into force in 1997.

Article I of the CWC states, in part, that8

1. Each State Party to this Convention undertakes never under any circumstances:

(a) To develop, produce, otherwise acquire, stockpile or retain chemical weapons, or transfer, directly or indirectly chemical weapons to anyone;

The CWC clearly also has a General Purpose Criterion applying to all chemicals as Article II defines a chemical weapon, in part, as:

(a) Toxic chemicals and their precursors, except where intended for purposes not prohibited under this Convention, as long as the types and quantities are consistent with such purposes.

The CWC is also subject to a review every five years and the latest such review took place in 2013.9

The responsible conduct of research

Why should a practising neuroscientist carrying out benignly intended civil research be interested in such international arms control issues? Surely, it might well be argued, there is enough to do keeping up with this rapidly advancing field and making a reasonable research contribution in his or her own area of cutting-edge research. That, however, would be to ignore the evolution of the scientific community’s conception of responsible conduct of research (RCR). As Rebecca Carlson and Mark Frankel of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) explained recently, the scientific community is getting better at teaching and observing the necessities of responsible conduct in regard to the internal operations of science, such as dealing with human and animal subjects, data acquisition and its management, and publication practices and responsibilities.10 However, they also argue that there is a long way to go before the scientific community can be said to have dealt adequately with its external research responsibilities. These cover aspects of the societal impacts of research, such as communication, advocacy and emerging technologies.

Two questions that really need to be asked are these. What evidence is there that, as the growing sciences of chemistry and biology have been applied to the development and use of chemical and biological weapons over the last one hundred years, advances in neuroscience have contributed to these hostile purposes? And what are the possibilities that such distortions of civil science might continue in the future? One way to approach those questions is to look at the weapon systems that have been produced by states and the extent to which they affect the nervous system.

The nervous system is made up of individual cellular units, including the numerous neurons that are specialised for the transmission of information to, from and within the central nervous system. Information transmission within a neuron is by electrical means, but transmission between neurons is predominantly by chemical means. Specialised neurotransmitter molecules are released from one neuron into the synaptic cleft and latch onto specific receptor molecules on the next cell in order to affect the operation of that following neuron or effector system (such as muscle). This, of course, opens up the possibility of manipulation of the nervous system by the introduction of other chemicals, like drugs for benign purposes or chemical agents for hostile purposes. It should be understood, however, that the nervous system does not act in isolation and is intimately linked to the endocrine (hormonal) system and the immune (defence) system.11 Thus, stress registered in the brain can lead to hormones being released that then cause the release of glycogen and glucose, readily available substrates for energy metabolism, whilst amazingly small amounts of some bacterial toxins can induce elevation of body temperature in the fever response to infection. Given that there are many different neurotransmitters, hormones and cytokines (of the immune system) and numerous cellular receptors for bioregulatory chemicals in the nervous system, it follows that as our knowledge becomes more detailed, more and more specific targets for manipulation – for benign or malign purposes – are likely to be revealed.

Chemical weapons

Michael Faraday is, of course, best known for his groundbreaking work on electricity in the first half of the nineteenth century. It is less well known that Faraday was also a significant chemist. He was, for example, the discoverer of benzene, which was to be of fundamental importance in the growth of organic chemistry later in the century.12 In later life Faraday was frequently consulted by officialdom for his views on scientific issues and during the Crimean War he was asked for his opinion on a proposed scheme to attack and capture Cronstadt through the use of a chemical weapon. As his biographer13 noted, ‘Faraday was sceptical of the plan and his report could not be interpreted as a favourable one’. Indeed, it was not until the First World War, after the growth of industrial chemistry in the latter part of the nineteenth century, that large-scale chemical warfare became possible.

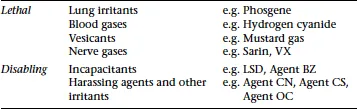

Chemical weapons can reasonably be divided into lethal and disabling agents14 (Table 1.1). Lethal agents such as phosgene and mustard gas were used in large quantities in the First World War, but it was not until the 1930s that nerve agents were first discovered, in Germany. Disabling incapacitating agents like BZ that affect the central nervous system, were developed after the Second World War as drugs began to be discovered that could help people suffering from some mental illnesses.

Acetylcholine (ACh), the first neurotransmitter molecule to be discovered, resulted from research by Loewi early in the twentieth century.15 ACh is manufactured in some neurons and stored in vesicles on the presynaptic side of the synaptic cleft between an ACh neuron and a postsynaptic neuron. When a nerve impulse (an electrical signal) in the presynaptic neuron reaches the synapse the ACh is released into the cleft, attaches to receptors on the postsynaptic neuron, and affects the electrical activity of that cell. However, precision in the information transfer is ensured because an enzyme called acetylcholinesterase quickly breaks down the ACh in the synaptic cleft. The constituent parts of the ACh molecule are then taken up for reuse in the presynaptic neuron.16

Table 1.1 Chemical weapons agents

Nerve agents are deadly because their main action is to inhibit the action of acetylcholinesterase and thus excessive amounts of ACh accumulate in the synaptic cleft and continue to affect postsynaptic cells. As there are ACh synapses in the skeletal muscles, the autonomic nervous system and the brain, it is no surprise that agents such as GA (tabun), GB (sarin), GD (soman) and the even more toxic V agents cause extensive disruption of bodily functions and can lead to death.17 The original G series of nerve agents were discovered by civil scientists working on pesticides in Germany before the Second World War18 and then,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I The Past

- Part II The Present

- Part III The Future

- Index