A proud ancestral record told of property, public service and fast tracks into prestigious social circles. But when the Honourable Wynne Alexander Hugh Godley arrived on the London scene, in 1926, there was little to pass down except the honorific title. High-flying ancestors had always dropped back down to earth.

In 1734, Mary, the daughter of County Armagh vicar Dr. William Godley, had married the Dublin-based trader Richard Morgan, an owner of land at Killegar near the village of Carrigallen in County Leitrim. Entrepreneurial skill ran no further in the immediate family, but their grandson John Godley reinforced the family fortune and estates through marriage to Katharine, a granddaughter of the Earl of Farnham. Ancestral land running scarce on the English mainland, the British Empire’s more recently ennobled often had to settle for tracts of Irish land without little assurance of its quality. But John was to turn his patch of ‘wet land in a very uninteresting boggy part of Ireland’ into ‘a handsome mansion house and a demesne of unsurpassed loveliness’, according to the notes of his great-great-grandson to come. Killegar House was completed in 1813 in the Georgian style, surrounded by gardens, lakes and forests that proceeded to withstand the tests of time rather more successfully than the stately home itself.

Wynne’s great-grandfather John Robert Godley (1814–1861) became the High Sheriff of Leitrim and in 1850 arrived in New Zealand to found the Canterbury colony—naming its capital Christchurch after the Oxford college from which he had graduated in Classics. Noblesse must oblige even in the grimmest of times, so it was a matter of family pride that, during the potato famines of 1845–1849, no one ever went hungry living on or near the now-extensive Godley estates. Indeed, John Robert was able to pronounce himself ‘exceedingly popular, from having done a good deal to procure employment and relief for the people’, in a letter to his fiancee Charlotte in 1845.

The Canterbury settlement scheme was partly a response to the dire poverty that has left many local families on the edge of starvation after the potato blight—the Godleys ’ largesse not stretching indefinitely beyond their boundary walls. It was also an experiment in a new self-sufficient, self-governing form of colonisation. John Robert campaigned to establish this throughout the British Empire on returning to the UK in 1852, having declined a nomination to govern the new province. He urged, in the first of three letters to Sir Colman O’Loghlen, ‘the necessity of Emigration on a very large scale from Ireland to Canada, in order to preserve vast numbers of our fellow-countrymen from perishing of want’ (Godley 2018: 3). He also remarked that such resettlement requires that emigrants be given state assistance to make the journey and find work, along with religious instruction ‘and other elements of civilization’. An almost casual mention that he had already outlined the plans to Lord John Russell, who served his first term as Whig prime minister in 1846–1852, highlights how vaunted the Godley political connections had become by this time.

Wynne’s grandfather John Arthur Godley (1847–1932) became the private secretary to William Gladstone (Whig prime minister 1868–1874 and 1880–1885) and was rewarded with a hereditary peerage (as Baron Kilbracken) for his supporting Home Rule for Ireland, without losing his attachment to the stately home there. He also served as Under-Secretary of State for India. It was in this capacity that, in 1909, he received the resignation letter of a junior employee called John Maynard Keynes , who was leaving the India Office to take up a post in the recently formed Cambridge Economics Faculty (Economist 2010). Finding diplomatic channels effective enough to remove any need for travel to the territories he administered, John Arthur lived mainly in the south-east of England where, in retirement, he would later entertain his infant grandson. The five-year-old Wynne noted on his grandfather’s desk ‘a pair of brass scales with rates of postage graven into it for all time… such a number of pence for “India and the Colonies” and so on’—affirmation that colonial governance was deliverable by post. John Arthur’s cousin, General Sir Alexander Godley (1867–1957), also performed distinguished colonial service, rising through the army to command the New Zealand Expeditionary Force during World War I, and surviving the traumatic engagements at Gallipoli and Ypres.

John Arthur’s ascent to Lord Kilbracken was a return to the glory of previous centuries, if a family tree traced by his descendants is ever proven correct. This names the bride of John Godley of Killegar as Charlotte, granddaughter of Charles Finch and Jane Wynne, whose son Charles took Wynne as the family name. The line then goes back to the Earl of Aylesford, son of Charles, the 6th Duke of Somerset. Four intervening generations connect him to Lord Hertford, son of the Lord Protector Somerset, with lines then going back to Queen Elizabeth I and King Henry VII. To outdo those English families that can ‘only’ trace their ancestry back to the Conqueror, this tree then connects via William I to Ferdinand the Great and Philip the Bold.

But deep roots were no shield against the out-of-character crosswinds. From these heights of administrative and military achievement, family fortunes began inexorably to slide. The second Lord Kilbracken, Wynne’s father Hugh John Godley (1877–1950), became a distinguished barrister and advisor to the Lord Chairman of the House of Lords Committees. He regained the Killegar estate, halting its decline if not beginning its refurbishment, and cultivated musical interests as an amateur viola player and frequent Bayreuth Festival visitor. But his offspring saw few of the benefits. ‘My father had all his fun well away from his family’ was the best of Wynne’s adult reflections.

Hugh’s behaviour and decision-making deteriorated under the influence of alcohol, with a similar effect on the family finances. So while viewed by the outside world as children of privilege, Wynne and his siblings had to fight their early way through looming aristocratic decay. The eldest, John Raymond Godley (1920–2006), inherited a Killegar House that steadily overwhelmed its occupants’ powers to renovate, or even heat the reception rooms in winter. John Raymond’s restoration efforts were set back by a serious fire in 1970, the damage from which was not fully reversed by the time of his death. His younger brother was destined to be passed around other childhood homes, which lacked the charm of Killegar’s surroundings and usually provided more heat than light.

Truncated Childhood

By the time Wynne, Hugh’s youngest son, was born in Paddington in 1926, his parents were already drifting apart. He remembered their occasional reunions as invariably stormy. The domestic disharmony was made worse by his older half-sister Ann’s bouts of mental illness. His grandfather, living a short walk away ‘in a large, ugly, overheated house called Hartfield’ where ‘every wall was dense with books’, became the inspirational figure for his first five years, providing much of the entertainment and education that was absent at home.

At John Arthur Godley’s imposing ex-colonial desk, Wynne learnt to draw and rub brass, was read stories ranging from Struwwelpeter (Hoffmann 1845) to Fanfan la Tulipe (Bilhaud 1895), and tested the permissible limits of picture book learning, ‘an illustrated book of Chinese tortures’ sticking especially in the memory. The two also enjoyed rural escapes with the help of his grandfather’s chauffeur Leany, who often drove them to one station in the Wolseley limousine and met them outside another, at the end of their steam-train ride. When he died in 1932, triggering a life insurance payout of ‘some hundreds of pounds’, Wynne was the only family member to whom ‘Grampapa’ left a small legacy. But the more enduring gift was a small wooden model of Redwing, a yacht, which was to accompany him on all subsequent travels.

Less satisfactory escape was provided by long spells in the care of other nearby relatives and friends, in whose luxurious houses Wynne experienced strict discipline and long spells of isolation. A serious infection, which largely destroyed the hearing in one ear, also delayed the start of formal education. This finally began at age 7, when he was entrusted to the respectable but often brutal regime of southern English preparatory schools. A year at nearby Ashdown House was followed by four years at Sandroyd, then occupying a stately home in Cobham, 40 miles south-east of London.

Here, Wynne’s Latin exercises—delivered by the brother of the novelist Robert Graves—included educational verses penned by his grandfather’s cousin Alfred Denis Godley (1856–1925). ‘ADG’ is perhaps best known for The Motor Bus, a modernised mnemonic for the five declensions, beginning:

What is it that roareth thus?

Can it be a Motor Bus?

Yes, the smell and hideous hum

Indicat Motorem Bum!

Implet in the corn and high

Terror me Motoris Bi […]

Despite his lighter verse sealing his fame, Wynne recognised Alfred as a serious classicist and poet, unfairly overshadowed by his more prominent uncle. As Oxford University’s Public Orator, ADG’s other unsung achievements included the eulogies composed in Latin for honorary degree ceremonies. Recipients of these bespoke benedictions included French Foreign Minister Clemenceau, composer Richard Strauss and pianist turned Polish President Paderewski. Wynne carried with him into later life a copy of ADG’s Ad Lectionem Suam, a reflection in English on the perennial challenge of delivering familiar lessons with the necessary semblance of novelty:

When Autumn’s winds denude the grove, I seek my Lecture, where it lurks

‘Mid the unpublished portion of my works,

[…]

Though Truth enlarge her widening range, and Knowledge be with time increased,

While thou, my lecture! Dost not change the least.

While the prep schools’ teaching permitted such jest and was of generally high standard, their regime was also brutal, with ‘an awful lot of beating’ to instil respect in their young charges (Godley 2008). Outside the school term, home life grew slightly calmer. The affair that wrecked his father’s first marriage led quickly to a new partnership, and Wynne got on well with his new stepmother, Nora. He managed to juggle this with rediscovered attachment to his artistic mother Elizabeth during her infrequent visits, while sharing teenage discoveries (including rum) with his older sister Kathleen. They and older brother John were ‘cocooned, during the school holidays, in total complaisance by a full complement of servants, gardeners, handymen and farm hands, of whose irony I was never conscious’ (Godley 2001: 4). Despite exposure to the other side of the property division, when visiting the labourers on his grandfather’s estate, the expectation of receiving domestic service would prove hard to shake off. Ten years later his close musical friend Richard Adeney observed that however sincere his wish to renounce aristocratic connections and make his own way, he still ‘treated waiters and servants as if he owned them’ (Adeney 2009: 114).

Although elder brother John was called up for service on an aircraft carrier, Wynne was too young for conscription and remained largely insulated from World War II. When Nora despaired of her husband’s reversion to alcohol, she began an affair with William Glock . A multiple instrumentalist and cultural journalist who later transformed the post-war broadcasting of classical music at the BBC, Glock (1908–2000) gave Wynne his first serious musical exposure and awakened his interest in orchestral instruments, particularly the oboe.

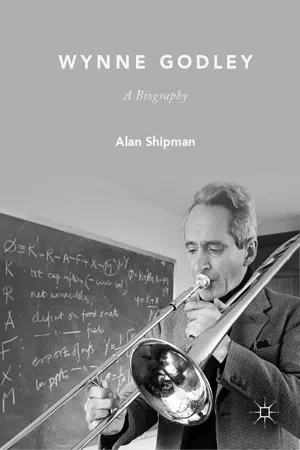

Wynne’s private school experience finally improved when, at age 13, he gained a place at Rugby in Warwickshire. It was here that he refined musical interest into genuine talent, willingly trying any instrument but gaining special proficiency at piano and oboe. Devotion to these, which drove a rapid ascent towards orchestral standard, limited the time spent on academic subjects. English, Classics and chess were the only ones to arouse real interest. The first two, fortunately, ranked high on the curriculum required for admission to top universities, while the skills of the third would prove useful for survival in the life beyond them.

Oxford, Berlin and Paris

Despite his variable motivations towards study, Wynne negotiated the school-leaving exams successfully and gained a place at Oxford. New College, so-called because it was founded over half a century after the university’s first (in 1379), was the creation of William of Wykeham, King Edward III’s chief minister and Bishop of Winchester, whose eponymous school he also created a few years later. It was the first Oxford college to admit undergraduates and, when Wynne arrived in October 1943, offered a congenial mix of serious tuition, music and the company of students who have been similarly spared the call-up to World War. Wynne had been admitted to read for the degree that began as Modern Greats, but evolved into the now famous philosophy, politics and economics (PPE). In contrast to the time that preceded them, the four years in Oxford proved to be ‘supremely happy’ (Godley 2001: 4), but did nothing to mark him out as one of the social sciences’ rising stars.

Happiness was reinforced by an overlap in studies with brother John, who arrived at Balliol in his mid-twenties after serving for five years, and had another four to go before becoming the third Lord Kilbracken. Also studying economics, John’s habit of reading late paid unexpected dividends when, in March 1946, he dreamt of reading horse-racing results in the next day’s evening paper. While living a typically impecunious student life among the spires, John’s inheritance still stretched to a credit account with a bookmaker in London. An accumulating bet placed on two horses whose names he remembered from the dream, and found in the morning paper, paid off handsomely: both ran home as winners at odds of 6:4 and 10:1. Speaking on a television documentary almost thirty years later, by the occultist Colin Wilson, John recalled Wynne joining him in the walk to buy the evening paper that broke the news of the win.

The prescient dreams remained sporadic, but John had another when he, Wynne and Catherine were visiting their father and stepmother at Killegar in the summer of 1946. This time the nocturnal horse’s name did not match the one that the village postmistress (speaking by phone five miles away) found in the columns of the only available newspaper. According to John, still sceptical of any paranormal powers, it was the more enthusiastic Wynne who suggested putting all their spare change on the one that sounded least dissimilar. It won, at 100:6, netting them £60—enough to have paid off their loans if student life had then required them. John next slumbered to a winner when borrowing Wynne’s New College room for extra study during the Oxford ‘long vacation’. By this time, frustrated by the bookie’s low credit limit, he tried to sell the names as tips to a newspaper, phoning them through ahead of the race to demonstrate their reliability. While the Su...