This book explores how Chinese angles form powerful cultural bridges connecting Shaw and his contemporaries to China. When different cultures meet, much time and effort can be saved if one knows where the cultural bridges are located. Just think of occasions when things appear strange, puzzling, and different, and yet when seen from another angle they suddenly become familiar and reasonable. The ability to see from another angle helps one discover common ground between cultures.

In the chapters that follow, we will explore the Chinese angles behind readings of Shaw in China, angles that also apply to the ways in which Shaw’s contemporaries around the world, such as Charles Dickens, Arthur Miller, and Gao Xingjian, are regarded. We will examine uniquely Chinese perspectives, but also position them within a larger framework. The negotiations between the focused and culturally specific standpoints on the one hand, and the diffused, multi-focal, and comprehensive perspectives on the other, create strategic moments that favor the readings of Shaw in China. Such tactics are transferable skills, also made use of by contemporary Chinese films and by the first ethnic Chinese Nobel laureate in Literature, Gao Xingjian, to create a global audience. The significance and impact of these Chinese angles can be seen in how frequently and extensively they have been used as cultural strategies to connect China to the world. The strategic interplays between the macro (centralized) and the micro (locally adapted) are not only literary techniques, they can also be found in other disciplines. For instance, in the Chinese economy, 宏觀調控 (hong guan diao hong), or macro-economic control, played a crucial role in focusing on the overall economic system, with individual adjustments to supply and demand that maintain national economic growth.

Few people have had as many contemporaries as did Shaw, who lived an unusually long life: from 1856 to 1950. His famous near-contemporaries include Charles Dickens (1812–70), who was born under the rule of King George III; Arthur Miller (1915–2005), who died when George W. Bush began his second term as President of the United States; and Gao Xingjian, born in 1940. Shaw’s plays and works also made good use of technological innovations, such as the invention of film, which challenged stage productions and captured huge audiences for blockbusters and Academy Award winners. Shaw was born while Charles Babbage (1791–1871), the “father of the computer” who originated the concept of a programmable computer, was still alive.

The following chapters will show how Shaw’s works were readily adapted to film and became the subject of popular microblogs in China. We will examine how Shaw and his contemporaries saw and wrote about China, as well as the ways in which some famous writers have been seen as key literary, theatrical, and cultural figures in the country. In addition, this book explores how the notion of “contemporaries” is constantly changing, as an author’s works keep acquiring new contemporaries of their own. Shaw’s works continue to be relevant to the Chinese, who use them to express how they themselves would like to be seen by the modern world. The Chinese angles on Shaw and his works developed as the country marched rapidly from a feudal empire under siege by colonialism and imperialism to the modern nation it has become, one that has assumed a prominent role in the global economy.

The Chinese angle applies not only to literary studies. As China enters the limelight in the global arena, and given the size of its market, it is strategic to study Chinese perspectives as cultural bridges. The topic is timely. Like Shaw, many visitors to the country came from the West. In the first nine months of 2013 alone, 19.36 million arrived in mainland China. Among these, 1.55 million came from the United States and 502,300 from Canada. 1 In 2013, China was ranked as the best overall destination in HSBC’s survey of over 7,000 global expatriates. 2 The number of Chinese visitors to the USA is breaking records too. According to Christopher Thompson, president and chief executive of Brand USA, America welcomed 1.47 million Chinese visitors in 2012, and by 2018 the number of Chinese travelers is expected to hit 4.7 million annually, which means they are going to be the biggest tourism group in the United States. 3 Given this intense traffic to and from China, there is a need to pay more attention to the interflow, to know not only how things look from Chinese perspectives, but also why they are seen in such ways—things may look quite different from a Chinese angle. It is impossible to expect cultures to understand one another fully, but knowing how things appear from a Chinese perspective will reveal the strategic points that would make exchanges with China easier and more efficient.

Shaw from a Chinese Angle

Seeing things from another angle often results in pleasant surprises and new perceptions. For example, Shaw attended the rehearsals of Sir Edward Elgar’s new String Quartet in E Minor, Op. 83, and Piano Quintet in A Minor, Op. 84. Just imagine the composer’s response when he received Shaw’s letter, dated March 8, 1919:

I am not sure that the vitality of the finale is not too much for that little snatch of waltz when the leader mutes his fiddle. A vision of you offering a haporth of sweets to some dear old lady who didn’t like classical music came into my irreverent head suddenly. If the tenor could just have made a little laugh at it with two notes! But don’t let me put you off it: you know the way things catch you sometimes at a queer angle. 4 (CL III 593, emphases mine)

People visualize in terms of what they know or can imagine, and sometimes this can be far removed from the original intentions of the author.

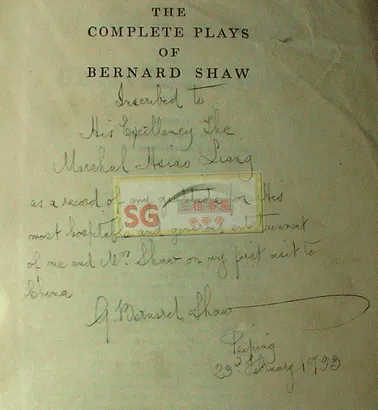

Shaw arrived at China in 1933 on his world tour and was scrutinized from Chinese angles immediately. In Shanghai he was invited to lunch by Madame Soong Ching-ling, widow of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, first president and founding father of the Republic of China. In Hong Kong Shaw had tiffin with millionaire businessman Sir Robert Ho Tung. In Beijing he was entertained by the young Marshal Chang Hsiao Liang, who was in effect the ruler of northeast China and much of northern China at that time. How impressed Shaw was by this last meeting can be inferred from what he wrote to Liang on the title page of the newly published Constable edition of

The Complete Plays of Bernard Shaw (1931): “Inscribed to His Excellency The Marshal Hsiao Liang as a record of my gratitude for his most hospitable and generous entertainment of me and Mrs. Shaw on my first visit to China. G. Bernard Shaw. Peiping. 23rd February, 1933” (Fig.

1.1).

According to The Telegraph, in 1933 Chang was hailed as China’s “man of destiny” and “China’s Napoleon,” unmistakable echoes of Shaw’s play The Man of Destiny (1895). 5 Shaw could never have guessed that the young Marshal he was meeting was soon going to change Chinese history. In the Xi’an Incident of December 1936, when Japanese aggression in China was intense, Chang Hsiao Liang kidnapped Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Republic of China at that time, to persuade him to stop fighting the Communists and instead form an anti-Japanese alliance. This resulted in the short-lived United Front combating Japanese aggression. Nevertheless, the cost was high: Chiang put Chang Hsiao Liang under house arrest for the next fifty-four years, until 1990.

Shaw’s meeting with Chang Hsiao Liang in China also foreshadowed another historical incident. On his return to England from China, Shaw told Hsiung Shih-I that the main reason for him visiting China was to see the Great Wall, 6 which he could do because of Chang. According to a report in The Pittsburgh Press of February 22, 1933, Shaw spoke for two hours with Chang and asked him: “How can the impending trouble be averted?” Chang replied: “As long as the Japanese military are in the saddle, there is no way of avoiding war. I see no solution but war. China is powerless to save the situation.” 7 Shaw accepted Chang’s invitation to fly over the Great Wall on February 24, 1933, only to beg the pilot to turn back when he saw a fierce battle between the Chinese Army and the Japanese there: “Turn back! Turn back!” he shouted. “I don’t like wars. I don’t want to look at this.” 8

Shaw was only one of the many foreign experts visiting China. Since the early twentieth century, however, he has been seen from multiple Chinese angles to authenticate cultural movements in China, and to create cultural currency that has had widespread cultural, social, and political repercussions. To understand the complex, and very often subtle, mechanisms behind these repercussions, comparisons will be made to the ways in which Shaw’s major contemporaries saw China, and were seen from various Chinese angles, to create desirable images of China. It will be shown how the multiple perspectives produced by Chinese angles act as powerful cross-cultural strategies that go well beyond one-to-one adaptations and influence. There is a nebula of forces shaping how the Chinese see and would like to be seen by the world, and how they project those forces onto literary works. The Chinese angles are both exclusive and inclusive.

Duality of the Chinese Angle

As can be inferred by the distinguished personages Shaw met in China, the Nobel laureate arrived as a famous foreigner. He was not seen as merely “Bernard Shaw”—or, in Chinese, “Xiao Bo Na” 萧伯纳 (last name first)—but in perspective as a famous foreign writer visiting China. Moreover, the Chinese angle under which he was viewed has two simultaneous aspects. First, it is informed by its Chinese cultural specificities, which may be quite different from Western perspectives. Second, it takes in the big picture, as it has a multi-focused vantage point, so that different subjects can be considered simultaneously in parallel to one another. Thus a particular subject exists alone but is also recognized in relation to other subjects. The importance of the network of social contacts and inter-personal connections can also be found in guanxi, an important concept in organizational behavior in China.

As an analogy, let us examine the opening ceremony of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. (This is significant, as Beijing’s bid for the 2022 Winter Olympics was also successful, making it the first city to host both summer and winter games.) In the 2008 opening ceremony, there were two very different processes at work simultaneously: a single-focused nation-building perspective and a multi-focused vantage point that depended on where the viewer was positioned. The central focus was a huge Chinese scroll painting projected onto an enormous LED (light-emitting diode) screen placed on the ground, which unfolded slowly during the ceremony.

First, there was a guided, single-focused, Chinese angle captured by the official cameras, broadcast live to the world on television and on the Internet. In a similar manner, Shaw and his contemporary authors were the focus of attention in being incorporated into the rhetoric of the Chinese nation, much like the camera’s coverage of the huge scroll painting using one shot at a time. At the opening ceremony, a global audience was guided by the camera to see the painting unfold, their perspectives conditioned by the camera’s vantage point. The slogan of the Beijing Olympics was “One World One Dream.” Via the camera, there was a single, unanimous, worldwide viewing. The entire viewing process showcased the Chinese nation’s most significant achievements, such as its four major inventions: the compass, gunpowder, papermaking, and printing. Likewise, the arrivals of Shaw, Dickens, and Miller in China were significant moments incorporated into China’s nation-building agenda.

Yet at the same time there was a diffused, mult...