Free the Water! (water tower tag painted by Antonio Cosme and William Lucka )

At school, they ask why I do it. I tell them that the water has a spirit. They’re like, ‘It does?’ (Ojibwe Water Walker , Reyna Davila-Day, as recounted by reporter Julie Zauzmer, 1)

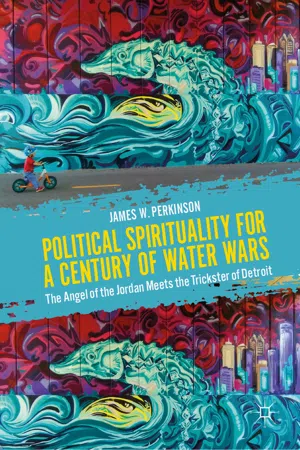

A helmeted child on a scooter plies a roadway before a huge mural—aquamarine sturgeon , shimmering Water Dragon, arising from roiling river at the Strait. Detroit in upper right corner with architectural icons “reduced” to insignificance before the gorgeous beast. Burnt rouge sky, as turbulent as the water, and sun-flash on the river, over which the rearing Fish-Queen bends, Her body and the swirling flow, indistinguishable. Sign of the age. Sign of apocalypse. Sign of this book (in its doubled layering of the upwelling waters, already hinting a major theme of Upper and Lower Waters struggling with each other). The graf is scarce two blocks from my domicile on Motown’s near east side—a commissioned work in the below-grade bed of the former Grand Trunk Railroad, since become pedestrian greenway, from river bank straight into the heart of Eastern Market, where thousands glean fresh produce at each Saturday’s farmer’s extravaganza, bringing the bounty of Michigan fields to the urban core since 1841. The child—an unknown passerby when my wife and I first clicked used-I-phone shots of the eye-feast in early summer of 2018. I had already approached the artist to ask permission for his tag to anchor my own literary work, based on an offprint hanging on my wall—purchased three years earlier to help generate legal fees to defend the “graffo-bomber” against a vandalism charge for a series of prior tags.

William Lucka is well-known in Detroit as a young blood from a black “hood, splashing blight with wake-up color and ‘woke’ politics . He and a comrade-in-aerosol had scaled a defunct water tower in the tiny municipality of Highland Park, embedded in inner city Detroit—first home of Henry Ford’s assembly manufacturing, now plundered and hard-pressed in de-industrialization’s ravages. In their renegade genius, the tower was made to host ten-foot high letters and a big black fist, shouting “Free the Water”—speaking back to the Emergency Manager’s draconian water-shutoff policy, then in full swing. Working under cover of wee hours’ darkness, the two taggers had paused after completing the piece to savor the sight and been caught up short by dawn and flashing blue-and-red sirens and spent the night in jail. In the ensuing legal process, Lucka in particular was targeted by a recently elected white mayor, hell-bent on making graffiti a felony offense, and the community mobilized in defense. Ultimately the charges were reduced to fines and community service, but the tag itself had echoed loudly across the city, before being “whited out.” Lucka’s sturgeon pic, however, had been commissioned by the Detroit River front Conservancy , a public–private partnership looking to transform the city’s international waterfront into a “world class” monument of community accessibility and arts. So the same basic message here amounts to fantastic work secured for approved use from a “Native” Son needing funds. But Lucka’s vision pulls no punches for those in the know. He tattooed the post-industrial viaduct remains with a freeze-frame of no mean invocation: sturgeon river-serpent, going back to the Triassic, favored in Three Fires Native lore as ancestor-teacher of a clan, honored in burial, anchoring dwelling at the bend, until reduced to isinglass glue and near extinction by Euro-colonial hubris, now, in this panorama, “resurrecting” like a freed Monster-Force of Beauty, staring respect and comeuppance. Here meet the deep past and near future of this great basin, signaled in art by a struggling seer, like a contemporary Jacob at a modern Jabbok , wrestling the hard concrete into def announcement that civilization as we know it is now clearly destined to end in a major “dislocation” of one kind or another.

Initiation into a Conundrum

But we begin in the middle, after Detroit is already le détroit du lac Erie, the Strait of River connecting Great Lakes Huron and Erie. And we begin with my own “baptismal” journey, a white boy evangelical from Cincinnati, Ohio, Shawnee terrain in deeper history, German-settled “Queen City of the West” when riverboat traffic was still the mainstay of Euro-transport coming from the East, plying the river called, in Iroquoian, Ohi:yó (“Good River”). My 1974 move north was a dream-confirmed quest to find safe spiritual harbor in an intensive experiment in Christian community living, begun in 1972, hosted in the Episcopal Church of the Messiah, one block removed from the Belle Isle Bridge over the Detroit River on Motown’s near east side—at the time, part of the poorest congressional district in the country. The motive was immature and fatuous—a tongues-speaking idealist on mission “to help” inner city denizens of color deal with their desperate straits—typical white supremacist hubris blind to both black skill and “cracker” disability. Only long slow “debriding” of that inherited skin-wound enabled a beginning recovery of some measure of vision, capable of more accurately perceiving reality under the surface of the stereotype. The intentional community of some 70 (at its height) Christians—black and white—committed to sharing economic assets, housing space, and lifestyle choices in common, articulated in a poverty-level budget on a per capita basis, provided the hothouse social environment capable of incubating a different set of habits of relating across the color line. Black anger and black humor—both disguised and in open confrontation—served as the prime pedagogy. The psycho-spiritual itinerary opened in that cross-racial social space had no sure maps and no clear guides. For me, as straight white male, lower middle-class in upbringing, the trajectory was decidedly “downward”—into a less well-resourced lifestyle, into the depths of intense black pain and extravagant black creativity in that eastside neighborhood, into my own turgid ignorance of life outside the vapid assumptions of white racial positioning.

Nine years into such an ever-continuing rite of racial initiation, seminary studies conferred new insights on liberation energies spiritual and political and another five years later, Ph.D. studies at the University of Chicago in theology, history of religions, and anthropology courses, began to supply new critical perspective. Return seven years later to the same eastside neighborhood to begin teaching at area institutions and begin spitting jazz- and hip-hop -influenced rhyme in spoken word settings, re-invigorated the intensive journey of “immersion.” Only now, the previous conventions of Christian predilection and theological idiom began to be torn open to a more visceral and fraught plunge into black arts innovation and motor-muscle articulation. Here the Spirit did not so much confine Herself politely to academic diction and ecclesial-propriety as explode, in bodies-in-motion, under a beat, speaking heat and comeuppance through deep rage and brilliant insight, forged under the regime of unrelenting white supremacist oppression and capitalist predation, transvalued in the crucible of ghetto creativity into irrepressible beauty. How respond to such as a white male, without perpetuating either white ignorance in running away from the blast-furnace of communication or white theft in participating without paying dues and honoring limits, remains the conundrum of instruction. All of this has been the on-going subject of my previous scholarly investigations and my on-going political collaborations.

But the baptismal trek “down” has also issued in another layer of confrontation, “underneath” the history of black subjugation. And that is the question of the land itself and settler-colonial decimation of Native American presence and power on this bend of river. As climate change roars ever more insurgently and neo-liberal globalization ravages the biosphere ever more recklessly and violently, it has become clear to this author that merely tweaking the 5000-year-old project of expansionist “civilization” to include a few more of its historic “victims” will not do. The demand is far more radical and insistent. How actually live in place without needing to pillage an “elsewhere” emerges as the irreducible question. And how cease the colonial apparatus of “disappearing” indigenous dwellers and suppressing their witness and on-going demands for redress, marks the litmus test for “de-colonizing” and “liberational” seriousness. The archaeology of a resolute “descent” through the layers of history systemically buried in political congress and educational finesse alike in this country (or for that matter, around much of the rest of the globe), cannot stop with unearthing and addressing white enslavement of Africans over the last 500 years—crucial and encompassing as that may be. It rather must continue on into the nether region of settler dispossession of Native peoples and the continuing colonial project of indigenous genocide that has never yet been either accomplished or interrupted. And that plunge itself issues in the ultimate interrogation of the hour already identified. Do plants and animals, waters and winds, soils and substrates (rocks, minerals , oils, etc.) themselves have “sovereign” rights to exist and flourish—unviolated by human desires to alter and enslave—as many indigenous communities assert? Or are their bodies simply “there” for us to use and use up as we please, un-beholden to any sense of wonder or respect or limitation or gratitude?

In these latter two engagements of the last twenty years of my fumbling amble, I have been joined by a life partner whose own quest began in the lone formal colony the United States has ever dared “declare” officially (the Philippines) but whose itinerary has likewise unfolded into a similar set of concerns and self-query. For her as Euro-colonized Filipina subject, undoing her Methodist-pastor’s-kid and American Peace Corps-trained sensibility has meant also coming to grips with a pre-Euro-contact, multi-thousand-year-old project of her own lowland-river-valley, Malay-and-Chinese-ancestors’ takeover of the domains of indigenous Ayta folk, pushed out of their traditional hunting grounds into the more mountainous interior, racialized as “Negritos,” and displaced continuously now as mining interests and development initiatives covet and conscript their lands anew, assassinating traditional leaders with virtual impunity in the process. For me, the encounters with indigenous resilience and demand here and in the Philippines has meant also turning toward my own deep past, underneath the Faustian bargain with whiteness and supremacy, behind settler-colonial presumption of sovereign rights to settle, enslave, and dispossess, back before “Divine Right” of kings and Christian insistence on universal “truth” in Europe, to what would have comported as indigenous in the pagan outback of western Eurasia in the form of Celtic and Nordic and Gallic practice or pastoral nomad culture (Alani, Scythian, Sarmatian, etc.) coming west off the Asian “Sea of Grass” century after century. Apart from the Sami people above the arctic circle in Scandinavian countries, there are no living ancestral communities to which I can turn. But there remain ancestral shards and fragments, myths and musics, food traditions and artifacts, yet bearing reclaimable memory of a more honorable way of engaging the mystery of human co-creation with everything else outside of civilizational hubris and violence. These now also shimmer with pedagogy and whisper correction for one otherwise cut off from estimable roots.

Thus Detroit as baptismal place—bioregionally unique but now globally desecrated in concrete and steel, brownfield and junkyard, brand-choice and financial preemption as any urban core on the planet! The city of my adoption stands forth as a layered conundrum of initiation and wild base of creation, demanding resolute embrace and on-going “exegesis” as the first and final “bible” of revelation and judgment for such a one as myself, determined to re-learn—from “all my relations,” present and past—what it means to be human.

Water at the Bend

In what follows, the contemporary water struggle in Detroit will anchor concerns that animate a “watershed reading”1 of both the bible and the Car City. The relentless drumroll of climate change has for some years now provoked deep questioning of modern assumptions for this author, and a turn to both ancient biblical text and Native indigenous practice for perspective on the query. In simple form, that questioning foregrounds locale in asking how we might live justly and sustainably “in place.” It also reads the conquest and commodification of place known as colonialism—redesigning some places as suppliers of goods and life for other places—as fundamentally counter to sustainability...