Spread of Public Sector Reforms

Governments have long initiated public sector reforms. In doing so, they have striven to improve existing systems and processes. In this sense, ‘reform’ indicates a ‘deliberate move from a less desirable (past) state to a more desirable (future) state’ and implies that a ‘beneficial change’ will take place (Pollitt and Bouckaert 2004, 15). Reforms are often introduced as a response to shortcomings of a previous system (Hughes 2003) and involve ‘doing the old things in different ways’ or discovering ‘new things that need doing’ (Halligan 2001, 8). Numerous definitions of public sector reforms have been offered by various scholars. Turner and Hulme (1997, 106) point out that one of the elements of the definition of administrative reform is ‘deliberate planned change to public bureaucracies’. Barzelay and Jacobsen (2009, 332) view it as a ‘process of managerial innovation in government’. Others, such as Pollitt and Bouckaert (2004, 6), view public sector reforms as a ‘means to multiple ends’. According to Lane (1997, 12) public sector reform is something that ‘no government can do without’ and ‘since all governments attempt it, each and every government must engage in it’. Even in earlier periods such as the Persian, Egyptian and Chinese empires, reforms to public administrative systems were implemented (Farazmand 1997). In more recent times, the end of the colonial period led to an increase in the number of independent states, adding to the urgency to engage in comparative public administration (Jreisat 2010). In more recent decades, with changes in areas such as the emergence of transnational networks, development of information and communication technologies and global economic development, public sector reforms have spread across countries extensively.

The spread and application of public sector reforms have not always been uniform. In applying public sector reform, for instance, most authors (e.g., Askim et al. 2010; Baker 2004; Cheung and Scott 2003; Common 2001; Halligan 2001; Jones and Kettl 2004; Klitgaard 1997; Nolan 2001; Olsen 2005; Pollitt and Bouckaert 2011; Wise 2002) agree that reforms are dependent on the context and culture of the countries in which they are applied. The choice of reforms depends on: different needs, political pressures and historical traditions (Aberbach and Christensen 2003, 504); specific structural and cultural characteristics based on the ‘administrative arena’ and ‘administrative tradition’ (Capano 2003, 788); differences in national reform paths and reform patterns (Hajnal 2005, 496); and the broader state–civil society relations within which the reforms are embedded (Brandsen and Kim 2010, 368). Even for countries seen as relatively similar in terms of development, there have been apparent differences in the implementation of public sector reforms. In a cross-country comparison of six developed countries, Gualmini (2008, 81) points out differences in the implementation of reforms between English-speaking nations (such as the USA and the UK) and Continental European systems. Similarly, Torres (2004, 109–110) notes differences in market-oriented reforms and management of human resources between the Anglo-American experience and continental European countries. Differences in implementation of public sector reforms also arise between Western and non-Western countries whose state histories and development trajectories are radically different. In the case of developing countries, the contextual differences within which reforms are implemented are stark, and transfer of public sector reforms from developed countries to developing countries is often fraught with inconsistencies and confusion during implementation. In some developing countries, values such as hierarchy, kinship and communal networks continue to influence the performance of the public sector (Andrews 2008; Cheung and Scott 2003; Klitgaard 1997). In addition, it has been argued that elite actors in governance systems in developing countries rarely encourage reforms since they gain from inefficient administrations (Baker 2004). Olsen (2005, 16) also argues that adopting reforms based on Anglo-Saxon prescriptions is likely to have ‘detrimental’ and ‘disastrous’ consequences, particularly when they are made within short time frames and under tight budgetary constraints.

In the implementation of public sector reform, there has been a mixture of successes and failures. The range of results has been attributed to both the nature of the reforms and variations in the context and culture of the public administrative systems when they were enacted. It is often the case that when public sector reforms are initiated, the context within which the reforms are applied is overlooked by the implementers. As a result, there is a clash of values and culture during the implementation of the reform, leading to its ineffectiveness. Vigoda-Gadot and Meiri (2007, 111) support this line of argument, pointing out that ‘cultural and personal considerations’, such as values, values-fit and the compatibility of individuals with their changing organisational environment, climate and culture are not considered in the introduction of new reforms. Understanding the national cultural variable is essential if we are to get an ‘understanding of the interplay between public institutions and the social context’, as national cultures influence the ‘structure’ and ‘performance’ of public administration (Andrews 2008, 171–172), and this hints at why administrative reforms vary in nature and follow different paths (Capano 2003, 782). One of the prerequisites for successful policy transfer is that countries must have a good idea of the policy in the originating country and the experiences of other countries with similar reform (Mossberger and Wolman 2003); and that governments must be clear about the problem to be solved at home and consider experimenting with various methods before deciding on the combination that best addresses their needs (Jones and Kettl 2004).

Bhutan and Public Sector Reform

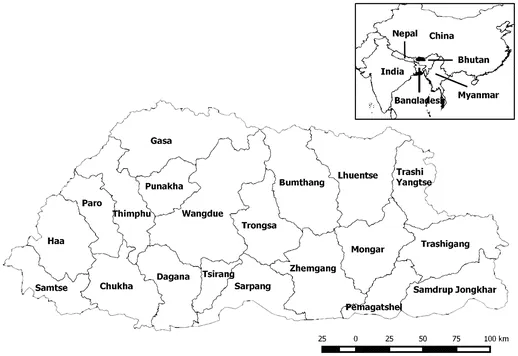

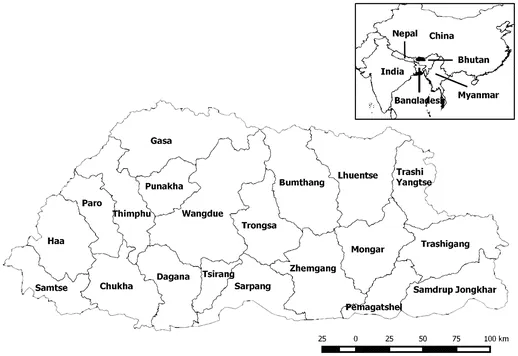

Amidst such a flurry of public sector reform initiatives, Bhutan, a small, land-locked country wedged between China to its north and India to its south (refer to Fig.

1.1 for an administrative map of Bhutan), has engaged extensively in public sector reforms since the 1960s, when it opened itself up to international engagement and initiated planned economic development.

With a total land area of 38,394 sq. km inhabited by approximately 730,000 people (NSB 2014), Bhutan is a developing country with a per capita income in 2013 of US$ 2330 (World Bank 2015). Bhutan’s pace of development has been relatively fast. Within about 30 years, from 1980 to 2012, life expectancy increased by 21 years, expected years of schooling by eight years and Gross National Income (GNI) per capita by almost 470 % (UNDP 2013). The start of development activities in Bhutan also resulted in changes to traditional institutions which were based on a strong tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. Multiple public sector reforms have been initiated between the 1960s and the current times. In 1972, the first set of civil service rules was drafted, establishing uniform service conditions for all civil servants and setting standards for employment and promotions. In 1982, responding to changing needs and a diversified environment, the Royal Civil Service Commission (RCSC) was established to motivate and promote morale, loyalty and integrity among civil servants by ensuring uniformity of personnel actions in the civil service (RCSC 1982). In 1990, the cadre system was introduced to minimise disparities in the entry-level grades and to provide career advancement opportunities. The most recent public sector reform initiated by the Bhutanese government has been the Position Classification System (hereafter referred to as PCS) implemented in 2006.The PCS represented a major tranche of public sector reforms including key components of performance management, recruitment, promotions and training. Bhutan’s public sector has played an important role in the development of the country, while simultaneously building its own institutions, organisations and capacities.

Bhutan’s public administration, as we shall observe in subsequent chapters, has a distinct culture based on the predominant religion in Bhutan (Tibetan Buddhism), and a large component of religious values percolates into the social and national culture. Many authors have observed the integration and intertwining of Buddhist philosophies with the state’s policy (e.g., Blackman et al. 2010; Mathou 2000; Rinzin et al. 2007; Turner et al. 2011; Ura 2004). Fundamental Buddhist values such as compassion, respect for life, striving for knowledge, social harmony and compromise have also impacted policymaking in Bhutan (Mathou 2000). The concepts and practices of Buddhism are often used as resources for the coordination of complex and interdependent public policies (Hershock 2004). Blackman et al. (2010), for example, agree that for new policies and processes to be successful in Bhutan, they should integrate Buddhist principles and existing Bhutanese culture. The size of Bhutan’s public administration is small, and the number of civil servants as of June 2012 was 23,909 (RCSC 2013), which was approximately 3.4 % of the total population. In general, the definition of the civil service in Bhutan includes all employees who are employed by the Royal Civil Service Commission under the conditions of the Bhutan Civil Service Rules and Regulations (BCSR 2012). The BCSR 2012 excludes categories of...