Conceptual art, as a historical art movement that emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s and as a point of reference for contemporary art practices, is generally identified by its use of language. For many, it has even redefined writing as an artistic practice. But how exactly was language used, and with what aim? Equally important, how has the presence of language in a visual art context affected and changed the ways in which art is talked about, theorised and produced?

Conceptual artists utilised language in various ways: identifications, statements, instructions, commands, observations, descriptions, propositions, citations, discussions and so on. These were often combined with photographs, objects, actions or locations, and were presented as captions, postcards, sketches or essays. Among other things, words appeared on the gallery wall, in the streets, in exhibition catalogues and artists’ books, and were handed out to spectators or circulated in art magazines and bulletins.

This book examines this juxtaposition of images and texts in conceptual art and specifically the cases where the visual is deliberately compared and contrasted with the textual—cases, in other words, where artists critically engage the relation between what one sees and what one reads. The terms “text” and “image” will therefore be used in their generalised categories. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, this book will show how the juxtaposition of images and texts was one of the strategies that conceptual art employed in order to expose and challenge several ideological and institutional demands placed on artistic practice. These demands included the production of visual and tangible objects, of objects that were unique and non-perishable, and of objects that could be easily designated as “art” and be largely qualified as vehicles of expression by their universal aesthetic value. Such demands marked the historical context of conceptual art dominated by American modernism, and remain relevant to contemporary art as a lucrative and globalised business.

Conceptual art is one of those art movements that has self-reflectively scrutinised the status of art. It advanced an institutional critique that interrogated the practices and traditions of the artworld, the gallery system and the modernist art discourse. It also advanced a socio-political critique that sought to redefine the function of art within the wider social sphere. Artists clustered under the term “conceptual” explored how meaning is materially and discursively created in the art context, and how artworks can manipulate the chain of signification and subvert meaning beyond that art context. The juxtaposition of images and texts, therefore, becomes one way of critically juxtaposing the site of visual art to other sites of cultural and social activity. It implicates the relation of art to theory and brings art’s critical and social dimensions to the fore.

Another keyword associated with conceptual art is “dematerialisation”. The call for a dematerialised object of art extended John Cage’s “dematerialisation of intention” and advocated against the production of stable art-objects exclusively destined for gallery display. In their seminal article The dematerialization of art, Lucy Lippard and John Chandler (1968) detect a tendency in the artistic production of their time to move away from producing finite objects and from object-making in general. They moreover identify within this tendency the potential to challenge the spectatorial expectations of the gallery visitors and engage them instead as participants; and to challenge the traditional responses to art, the materials typically associated with it and the critic’s role in evaluating the work’s formal or emotive impact.

1.1 Why Language?

But the question remains: Why use language? Language gives particular sociability to art’s critical gesture since it is the means of interpersonal communication. The use of language also capacitates an engagement with the context of artistic production. This includes how an artwork is produced, received and understood, as well as the place that it occupies culturally, as part of a tradition of production and in society more generally. In short, it foregrounds how and what art communicates. In previous artistic movements such as the Russian avant-garde, the dialogue between the visual and the textual derived from the reconceptualisation of art as an active agent in social change (Grey 1986). For Futurism, Dada and Cubism, an experimental approach to visual and poetic representation was supported by typographical innovation (Drucker 1994). In the case of conceptual art, the historical context of the 1960s and 1970s was marked by American modernism, the growth of the art market and cultural imperialism, socio-political shifts at a global scale and media propaganda, as well as reconsiderations of the role of discourse, language and culture in capitalist societies more broadly.

American modernism and in particular the formalism of Clement Greenberg became the most theorised and predominant model for artistic production. It was materially supported and discursively promoted by wealthy metropolitan museums with large-scale exhibitions such as New York Painting and Sculpture 1940–1970 (16 October 1969–1 February 1970, the Metropolitan Museum of Art), which presented more than 400 works. It also enjoyed corporate funding such as that from the Guggenheim, the Rockefeller and the Ford Foundations, which was explicitly aligned to their political programmes. It is to this conjuncture of artistic production, marketing and discourse that critically engaged conceptual art brought attention. In turn, that this conjuncture remains under scrutiny is one of conceptual art’s contributions to contemporary art and criticism.

In a plethora of texts, modernist art discourse defined the experience of art as universal and unmediated, a private affair of contemplation away from any social or political concerns. The production of modernist narratives exponentially increased during the Cold War. At the same time that anti-imperialist and revolutionary struggles throughout the world negated the self-declared dominance of capitalism and workers’, students’ and social rights’ movements rejected its institutions, American modernism functioned as a placeholder for bourgeois values and capitalist ideology. It became instrumental in the United States’ programme of cultural colonisation—in particular abstract expressionism, which was celebrated as a truly American art form and a triumph over politically committed art (Cockcroft 1974). In Latin America, American modernism occupied the artworld through what was advanced as the “internationalisation of style” yet took place in a social context characterised by imperialist exploitation, US interventionism, consecutive military dictatorships, media propaganda and fierce social repression.

In this historical context, many conceptual art practices incorporated or emerged as a critique of American modernism and its associated ideas regarding the autonomous and disinterested artwork, the uniqueness of the artistic genius and the private interests of art. They challenged the hierarchical and ideological divisions between the artist as the producer, the critic as the qualifying expert and the viewer as the consumer. They opposed the isolation of art from other social activities and political concerns, and criticised capitalist society and consumerist culture. This was done by using language but also by utilising the media and the press, staging public interventions, carrying out sociological research and developing activities outside the official gallery networks. Indeed, conceptual art can be seen as modernism’s nervous breakdown (Baldwin and Ramsden 1997, 32).

Notwithstanding the focus of this book on the critical interests of conceptual art, it should not be assumed that every conceptual artist was interested in advancing an institutional or a socio-political critique. Using language was often simply a matter of following the trend, or a marketing strategy that both artists and galleries employed because of the low costs involved in the reproduction and dissemination of text-based works. It is important therefore to emphasise the difference between a critical use of language and a symptomatic proliferation of printed matter that stated nothing further than the obvious. A further reason for the increase of textual production has to do with documentation. Photographs, project descriptions, letters, sketches, notes and instructions were used as a confirmation of an absent work or idea after the event. These attracted the interest of collectors and institutions who became instrumental in conferring to such paraphernalia of the creative process the status of art and a price tag to match.

Another historical factor that conditioned the use of language in conceptual art was the state of affairs of scholarship. While the modernist art discourse dominated the artworld, analytic philosophy from the mid 1950s onwards refuted the accountability of language for universal truth and demanded deeper attention to its use. This method of analysis revealed logical problems in the expression theory of art that held it to be a universal vehicle of emotions, and became the basis for a systemic and culturally specific understanding of the artworld (Danto, Dickie). In addition, the incorporation of Marxist dialectics in the analysis of society and culture exposed the workings of ideology, helped conceptualise the processes of mystification and alienation, and demonstrated how narratives structure social life (Barthes, Althusser, Foucault). It particularly showed how, in consumerist cultures where the media and the official cultural outlets propagate whatever aspect of reality better suits the financial and political interests of their stake-holders, the public space of language becomes subverted. By the end of the 1970s, the newly established discourse analysis and visual culture studies underlined the social and political dimensions of both language and art as sites of ideological conflict; and a social history of art developed with influences from Marxism (Hauser, Clark), and later feminist critique and critical theory. These theoretical developments contested the ideological investments made in the object of art as well as the function of discourse in normalising the experience of art.

As such, the historical context of conceptual art was, in general, characterised by reconsiderations and reevaluations of processes across the cultural and social spheres. In turn, conceptual art instituted a critical enquiry into the production and function of art. This causes certain difficulties in discussing conceptual art. Some of its propositions, for example that other artistic means beyond painting and sculpture are eligible, may now appear self-evident. Returning to conceptual art is important, however, since it initiated crucial debates, still unresolved today, regarding the role of institutions and the market, the relation between theory and practice, the relation between art and politics, and the hegemonic practices of art history.

Let us return to the starting point of this book—conceptual art’s critical engagement with art and society through the juxtaposition of images and texts. Too often, conceptual artworks are considered to have failed to suppress the aesthetic experience of art or to be authoritarian versions of the ready-made (Krauss, Buchloh, de Duve). This may be relevant to works that did not aim to address or that did not succeed in interrogating the support systems which made them possible. As a result, they may have dematerialised their object (in the sense of lacking formal restrictions of execution) but their propositions as works of art could still be absorbed by the Greenbergian paradigm of a formalised, introvert and ahistorical art. At the same time, many contemporary art practices seek to specify and call upon a “strong” conceptual art tradition of prioritising the “idea”. This enables them to use their own relation to discourse as a form of legitimation and to justify their celebrated self-referential status (Osborne 1997).

By these accounts, the position of conceptual art seems paradoxical, having been put to use in serving different, and often competing, interests. Yet understanding how artistic production is wrapped in a discursive field is another one of conceptual art’s most important contributions. As for the general conception that conceptual art prioritised the idea behind the work, this is only one side of the story. To be exact, conceptual art demonstrated the dependence of art, its experience and meaning on context. It specifically showed that the licence to claim that one is only interested in a something (an idea, a significant form, a universal aesthetics) and that nothing else matters can only be supported within particular discursive and ideological frameworks. In the case of conceptual art, the most predominant of such frameworks are modernism and its ideological investments in the aesthetic; the commodification of art and curatorial anxieties in classifying art-objects; and (cultural) imperialism. It is these frameworks that critically engaged conceptual art practices sought to expose and challenge.

In order to do so, works from this period dislocated and recontextualised not only different types of objects but also modes of production and systems of interpretation. They drew attention to the habitual ways of producing, looking at and theorising art, and contested the hierarchies of value and meaning that operate across the space of art as a social space. In search of resources and alternative frames of reference, artists turned to subjects that were considered to be beyond the scope and established interests of artistic practice such as philosophy of language, logic, mathematical and semiotic systems, official discourse, legal speak, the everyday, mass media and advertisement. They juxtaposed seemingly incompatible discourses in order to generate instances of critique and reflection on the frameworks of interpretation and evaluation, and advanced a method of critical looking that could be transposed from the context of art to other spheres of activity and vice versa.

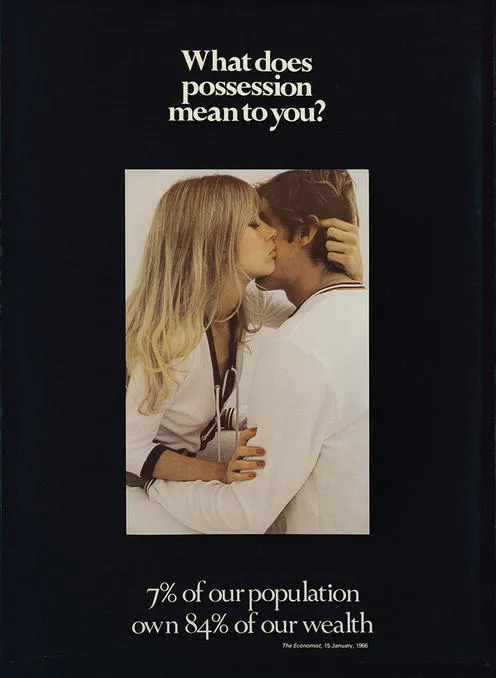

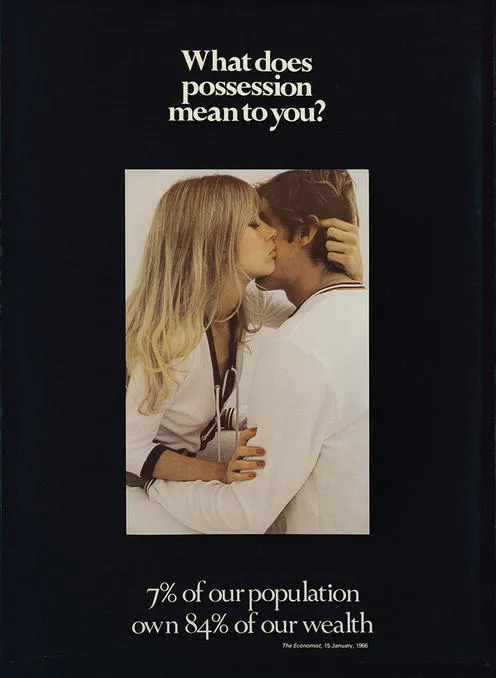

To be able to sustain this critique, the conceptual artwork remains provisional, logically inconclusive or in oscillation between the obvious and the absurd. This creates a discontinuity of meaning that confronts the viewer and can only be resolved by recognising both the work’s claims and the frameworks that determine how it is produced and received. Consider, for example, Victor Burgin’s work

Possession (1976). Produced to accompany an exhibition at the Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, it was reprinted in 500 copies and fly-posted across Newcastle (Fig.

1.1).

This work draws external resources in order to communicate its critique and exemplifies what I will call the

loan rhetoric of conceptual art (I return to this in Chapter

5). Utilising distinct systems of reference, discourses and vocabularies, this

loan rhetoric becomes a means to critically situate artistic practice within the material and discursive contexts that make it possible

and a means to interrogate the practices which operate within these contexts. Image and text juxtapositions, therefore, do not only provide a route to consider the role of language. More crucially, they become a way to engage the social function of art.

1.2 About This Book

This book offers an interdisciplinary study of image and text juxtapositions as they were used critically in conceptual art. It examines the production and reception of works in the late 1960s and the 1970s, and draws its main examples from the historically established triangle of exchanges across the United Kingdom, the US and Argentina. It specifies how artworks communicate in context and evaluates their critical potential to challenge the frameworks that determine how art is produced, theorised and experienced. It proposes three methods of analysis that consider the work’s performative gesture, its logico-semantic relations and the rhetorical operations in the discursive creation of meaning. Resources are drawn from art history and theory, philosophy, discourse analysis, literary criticism and social semiotics.

These theoretical frameworks offer a methodologically well-structured mode of analysis of the object in question both at the time of the event and from our current historical standpoint. They are epistemologically efficient in acknowledging the different contexts of the creative act (the material, discursive, institutional and historical context), and in specifying how the act functions within and impacts these contexts. They specifically attend to a work’s material presence, interaction between different elements and contextual relevance. Analytic philosophy and speech act theory were historically available and of interest to many conceptual artists, and the concept of the performative has been widely ap...