In her 2011 book Cruel optimism, Lauren Berlant identifies the return of ‘DIY practices’ of making do and getting on—of holding onto dreams and persisting even in the face of their costs—as emerging from people’s ‘hope that changing the white noise of politics into something alive right now can magnetise [in them] to induce images of the good life amidst the exhausting pragmatics of the ordinary’s “new normal”’ (Berlant, 2011, p. 261). At a time of growing employment uncertainty, shrinking arts funding, and widespread governmental policy rhetoric on encouraging small business, the exponential rise in the number of creative micro-enterprises across much of the industrialised world is clearly part of this ‘new normal’ as we ‘transition from the liberal to the post-neoliberal world’ (Berlant, 2011, p. 261). Within wider patterns around the privatisation of individual responsibility for one’s economic position, creative self-employment remains a financially risky undertaking, often pursued at the expense of financial security. The ease of establishing a professional business profile and the ability to network and market via social media provide nascent creative entrepreneurs with a sense of being real, sustainable, and significant, and function as a justification to self and others for continuing along this path. But for many, social media is less a miracle promotional tool and more an expected baseline requirement in maintaining professional self-branding without necessarily leading to any significant sales or financial return for effort (see Luckman & Andrew, 2017).

In this chapter, we argue that the growth of design craft self-employment is masking a ‘new normal’ of considerable unemployment as well as under-employment, especially among women. In this way, for many makers, pursuing a craft-based creative micro-enterprise can thus be seen as the epitome of Berlant’s ‘cruel optimism’, whereby that which we may desire ‘is actually an obstacle to [our] flourishing’ (Berlant, 2011, p. 1). What emerges is a balancing act, whereby the perceived non-economic rewards gained from pursuing life in the creative risk economy are seen to be worth the economic trade-offs involved. The social and economic costs to individuals, families, and the wider society of all this effort, risk-taking, and sublimation from public debate of larger issues around family friendly employment are profound and require greater attention as part of wider cultural and economic policy making.

The empirical data informing this chapter are drawn from a three-year study investigating how online distribution is changing the environment for operating a creative micro-enterprise, and with it, the larger relationship between the public and private spheres. A key research question is: What are the ‘self-making’ skills required to succeed in this competitive environment? The project focuses on the contemporary Australian designer–maker micro-economy, which is at present experiencing unprecedented growth as part of the larger upsurge of interest in making as a cultural and economic practice. It aims to:

identify the attitudes, knowledge, and skills required to develop and run a sustainable creative micro-enterprise;

analyse the spatial and temporal negotiations necessary to run an online creative micro-enterprise, including the ways in which divisions of labour are gendered; and

examine how the contemporary creative economy contributes to a growing, ethics-based micro-economic consumer-and-producer relationship that privileges small-scale production, environmentally sustainable making practices, and the idea of buying direct from the producer.

We recognise that not all handmade micro-entrepreneurs are at the same stage of their career or have the same origin story; hence, this qualitative, mixed methods national research project consists of three parallel data collection activities: semi-structured interviews with established makers; a three-year longitudinal mapping of arts, design, and craft graduates as they seek to establish their making careers; and a historical overview of the support mechanisms available to Australian handmade producers. At the time of writing, the project had interviewed 18 peak and/or industry organisations (involving 22 people) and 59 established makers, and had almost completed the second round of interviews with emerging makers (Year 1/‘1-Up’ = 32; Year 2/‘2-Up’ = 25). The project employs this phenomenological approach to offer a rich ‘insider’ perspective on creative micro-enterprise. Semi-structured interviews of this kind are the best tool available for capturing the work–life stories of creative practitioners in their own words. People are asked to identify key personally and professionally decisive moments in their life histories, enabling us to identify the kinds of skills and personal qualities that makers draw upon, and the impact of wider entrepreneurial and other discourses that impact upon the decision-making of individual makers. Many of them identify creative micro-enterprise as a work–life model they believe to be personally and environmentally (if not economically) sustainable and located within the growing alternative economic networks afforded by the growth of the Internet (Anderson, 2006; Gibson-Graham, 2006).

Making (as) a living?

Within our cohort of research participants, both emerging and established, we are finding a wide variety of interests, work experiences, and career development motivations. The career profiles of Australian makers parallel the four key profiles identified in the UK in the Crafts Council

Craft in an Age of Change report (BOP Consulting,

2012), namely:

Craft careerists:committed to the idea of craft as a career, they move to start their businesses shortly after finishing their first (or second) degrees in craft-related subjects [34% of our established makers]

Artisans:do not have academic degrees in the subject but nevertheless have made craft their first career [40% of our established makers]

Career changers:begin their working lives in other careers before taking up craft as a profession, often in mid-life [19% of our established makers]

Returners:makers who trained in art, craft or design, but who followed another career path before ‘returning’ to craft later on [7% of our established makers]. (p. 5)

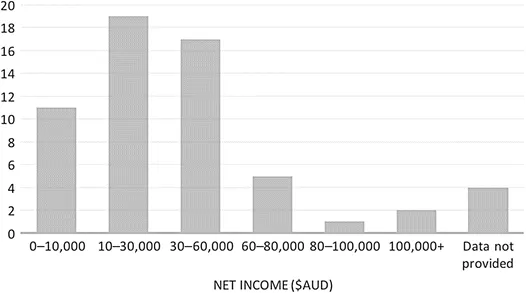

What unites these diverse experiences, however, are relatively low levels of financial return for effort. For despite the popularity of handcrafted bespoke objects around much of the industrialised world, and the ease of setting up a business identity and launching it online, the vast majority of both our emerging and our established maker research participants are not generating significant net income from their creative practice (see Fig.

1 for the established maker income). One of our participants reflected on this issue and recalled conversations she had with a number of fellow stallholders at a major design craft market:

PK:Oh I’ve had some funny discussions with people who, and I know it’s not all about this, but they make no money and now I still see them back the next time and the next time and the next time, and there’s just this idea that there are so many markets everywhere and people must be making money from them that’s why there are so many markets, but it’s not really the case. I think people are using them as promotion as well. (Pip Kruger, Emerging Maker, http://www.pipkruger.com)

The financial precarity of craft making is a recurring issue in our interview discussions:

CD:it’s not all about money but you don’t make much money.

Q:You didn’t get into art to make money?

CD:No if I wanted to make money I would do a job. (Christina Darras, Established Maker, http://christinadarras.com)

PM:Now she probably is the only one I know about, who is surviving or still making money just out of her art work. … I don’t make a lot of money out of my craft. (Pip McManus, Established Maker, http://members.ozemail.com.au/~pipmcmanus/mainpage.html)

Q:So in that year, has your involvement in the creative sector changed?

A:It’s collapsed (Laughing). … No it … changed, oh I tried really hard, we did, I did a number of markets, different types of markets, selling online, all that stuff. I just think no one wanted scarves, I don’t know, or they were too expensive, I’m not sure. I got a few requests, so I made a few scarves under order which was nice, but it was, that was just 2. So actually I didn’t make any money, because the markets were, the cheapest market I could find was $65 a stall. So I had to get myself there, it was 4 hours [away]. … So I was siphoning money basically, … I borrowed off my parents $6000 for different things and so I still owe them. But I just, it wasn’t working and we’re trying to buy a house and [my partner] was like, ‘Well what’s our future going to be like?’ So for retirement and whatnot, no super obviously was being fed into my account. So we had a bit of a talk, and so I looked for part-time work in my old profession which is dental assisting. And I found a job and it, and it’s actually I, I’d forgotten it’s really nice helping people. So I’ve gone back to that and part-time but because childcare was so expensive, I did initially have 2 days where I was going to concentrate on [my business] and that childcare was so expensive it went up to $120 a day. (Emerging Maker, Victoria)

But it is not all ‘doom and gloom’, with some of our makers engaging in economically successful—or at least sustainable—self-employment and small business. Defying many traditional narratives around artistic careers, what is seen as key here is making the call to take oneself seriously as a creative professional, and willingness to work the hours and engage in not just the creative side of things, but the things required to run a small business:

while you know it’s really ingrained that you can’t make money as an artist, I’ve always been able to say, well actually my parents are artists and they have been full-time artists you know now for about 20 years. [So] I’d really like to be able to say that to people and say, it’s perfectly possible don’t say it’s not. But you have to … I think one of the problems is people actually don’t work hard enough, and I know that sounds a bit cynical but, and I say it a little bit I guess from my own point of view, I think you can have this idea of, ‘oh I’m going to be an artist and it will be so lovely, and I’ll do a bit of work and I can sell at exhibitions’. Anyone who’s making full time money at art is working full time at least. (Established Maker, Queensland)

Modest incomes are being made by some participants in our study (see Fig. 1); our suspicion is that that those people offering no response to the question regarding income represent mostly makers with such a small turnover that they are effectively either just breaking even or perhaps running at a loss. A few may also be those doing okay, but feeling sectoral discursive pressure not to disclose exactly how well.

These income figures need to be considered not only through the lens of traditionally low-paid artistic work, but also in terms of the gendering of the designer–maker micro-economy. While inclusive sampling techniques seek to get a geographic and practice-based spread of research participants, our research participant cohort still tends to reflect the gender biases of the sector, with women constituting 82% of our peak and/or industry organisation interviewees, 82% of our established maker interviewees, and 81% and 84% (Year 1 and Year 2) of our emerging maker interviewees. Furniture making is one of the areas th...