A Greek Tragedy

Greek Tragedies were used to present an audience with a moral dilemma and invite them to think what they would do in similar circumstances? (Erskine and Lebow 2012).

By the time the Irish Republican Army (IRA) declared their ceasefire on 31 August 1994, Northern Irish party and public opinion had been polarised by twenty-five years of intense violence which killed approximately 3700 people and injured 40–50,000 out of a population of about 1.5 million. The IRA demanded a united Ireland, no IRA decommissioning and no return to devolution at Stormont. Unionists favoured the continuation of the Union, opposed powersharing and were against talks with terrorists. What would you do to achieve peace?

Idealists claim

straight talking and

honesty is possible. They deride ‘politics’ and use ‘

magical thinking’ to avoid tragic dilemmas:

Republican Idealists claim unionists are really nationalists who don’t realise it yet.

Unionist Idealists claim nationalists will become unionists once they appreciate the benefits of the Union.

Populist Idealists claim that ‘the pure people’ will find a ‘common sense ’ solution through mobilisation and dialogue.

Realists , by contrast, face up to the tragic, moral dilemma and the imperative to seize the opportunity to end a vicious conflict. Performing the Northern Ireland Peace Process uses a theatrical metaphor in defence of the pro-peace process political actors who used their ‘political or theatrical skills’ —including deception and hypocrisy—to bridge the gap between divided actors and audiences in order to reach an accommodation (see Dixon 2008; Dixon and O’Kane 2011 for introductions to and contrasting perspectives on the conflict see White 2013, 2017 for lessons of the peace process and theories of international relations).

The peace process represents, Realists argue, a ‘triumph of politics’ and representative democracy . Yet in Britain and Ireland the political skills that were so successful in achieving peace continue to be almost universally denounced (Chapter 10). The implication is that Idealists are correct, ‘a straight talking honest politics’ is both possible and would have been effective in achieving peace. Realists respond that since deception is inevitable in politics (and social life) then all Idealist claims of honesty are deceptive. The theatrical metaphor is used to explain why such deception is inevitable and, often, justifiable.

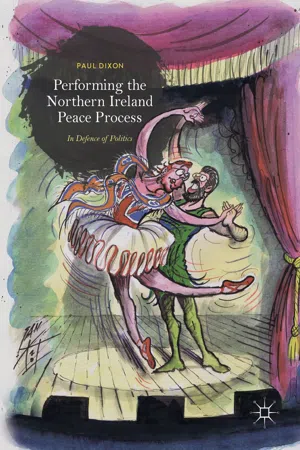

The theatrical metaphor has been a popular device among political and media actors to explain the peace process. ‘Political theatre’ or just ‘theatre’ was used to refer to an event constructed by political actors to attract the attention of the ‘audience’. ‘Choreography’ (although it refers to dance rather than theatre) was used to describe the reciprocal moves on stage made by unionists and nationalists to take care of their ‘audiences’ and achieve agreement. Speeches or press conferences were ‘stage managed’ to shape the perceptions of the audience. ‘Smoke and mirrors’ was used to describe the deceptive and illusive nature of politics. Political actors found themselves in the ‘spotlight’ or taking the ‘limelight’ from one another. David Trimble, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) MP, did not want to be ‘upstaged’ by Ian Paisley, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) leader, at the Orange parade at Drumcree in 1995. Demands that were made obvious by being put ‘up in lights’, like decommissioning , were more difficult to back down from. Political actors are criticised for ‘grandstanding’ or ‘playing to the gallery’. Journalists talked to politicians ‘behind the scenes’ or ‘back stage’. The cartoonist Ian Knox produced some insightful cartoons demonstrating the theatrical nature of politics (Knox 1999: 37; Turner 1995 for another astute observer). Tim Loane’s play Caught Red Handed (2002) draws attention to the theatrical performances of the DUP in order to ridicule its anti-peace process politics.

This prologue introduces the book and gives an overview of its themes. First, evidence is presented to show that deception was used to progress the peace process. Second, the ‘political actor’s dilemma’ refers to the problem that politicians have in defending their successful, ‘pragmatic Realist’ approach to the peace process which employs deception. The third section describes, the popular and ‘Populist Idealist’ condemnation of deception and belief in the possibility of a ‘straight talking honest politics’ (this was the slogan of Jeremy Corbyn’s campaign for the British Labour Party leadership). Fourth, there is an outline of the Constructivist (or Left) Realist defence of politics and deception using a theatrical metaphor. This leads to a discussion of where the ‘truth’ about the peace process can be found (if it cannot be found in the ‘front stage’ performance of political actors). Media actors tend to reveal the theatricality of politics in order to condemn politics as deceptive or else to favour some political actors over others. Academics are also actors and the academy is a domain in which power affects the production of knowledge about the peace process. Finally, the theatrical metaphor can be extended to social life to show how it is not just political actors but the audience that also performs and deceives.

The ‘Dirty’ Politics of the Peace Process?

Judgement is required in deciding whether or not political or other actors have deceived. Politicians can always claim that it was not their ‘intention’ to deceive or be ‘hypocritical’ (hypocrisy is playing a part, pretending or wearing a mask). Since we do not have direct access to the mind of the politicians, we must judge whether it was a highly likely or a highly foreseeable consequence of their actions and statements that other actors and the audience would be deceived (see Chapters 6 and 7 for a discussion of deception). The theatrical metaphor is used to suggest that some aspects of politics are like some aspects of theatre (see Chapter 2 on the theatrical metaphor). Realists argue that deception is pervasive and necessary in politics and so are not surprised at the extent of deception during the peace process.

In 1993, during the ‘behind the

scenes’ negotiations between the British

1 government and the IRA (

1990–1993) , the British representative offered the political wing of

the IRA media advice on how to attack the British government. Sinn Féin should emphasise

that the government was a reluctant participant in the peace process:

… Sinn Féin should comment in as major a way as possible on the PLO /Rabin deal [in Israel /Palestine]; that Sinn Féin should be saying ‘If they can come to an agreement in Israel, why not here? We are standing at the altar why won’t you come and join us’.

It also said that a full frontal publicity offensive from Sinn Féin is expected, pointing out that various contingencies and defensive positions are already in place. (Sinn Féin 1993: 41)

‘Front stage’ the IRA was bombing Downing Street (1991), the City of London (1992, 1993) and Warrington (1993), killing two young boys, Jonathan Ball (3) and Tim Parry (12). ‘Behind the Scenes’ political actors who were antagonistic towards each other on the ‘front stage’ were cooperating, exchanging speeches, choreographing their moves and giving media advice. On 1 November 1993 the Conservative Prime Minister, John Major, told parliament that he was not talking to the IRA and the thought turned his stomach . Four weeks later the British government’s ‘back channel’ talks were revealed.

After the

IRA’s 1994 ceasefire the peace process stalled over

the decommissioning of IRA weapons. The British government’s position was ‘

salami sliced’ away. Decommissioning was supposed to take place:

Before Sinn Féin met British government representatives (1994),

During all party talks (1997–1998),

At the end of all party talks (April 1998),

Before prisoners were released (September 1998), and

Before Sinn Féin participated in the Executive (December 1999) (Dixon 2008: 241–257).

IRA decommissioning began in October 2001 , shortly after 9/11 and nearly two years after Sinn Féin first entered government.

The Belfast (or Good Friday) Agreement (BFA) 10 April 1998 was choreographed in order to maximise its support among unionist and nationalist audiences. Prior to the Agreement party and public opinion seemed to be polarising rather than converging. There was little public expectation that a deal would be struck. The Agreement was ‘constructively ambiguous’, deliberately scripted to be presented in different ways to different audiences (Mowlam 2002: 231; Chapter 6). The unionists were told that the ‘Belfast Agreement’ would strengthen the Union, Nationalists that the ‘Good Friday Agreement’ was a staging post to a united Ireland. Mo Mowlam, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, claimed that in the BFA, ‘There are no winners or losers’ (News Letter, 20 May 1998). During the subsequent referendum campaign on the Agreement, in May 1998, the British Prime Minister Tony Blair (1997–2007) deceived the audience on the implications of the BFA (Chapter 6). He claimed the Agreement meant that until there was IRA decommissioning republican prisoners would not be released and Sinn Féin would not sit in government. This referendum was passed by an overwhelming majority of nationalists but by a bare majority of unionists. Within 2 weeks of the referendum a bill was published and legislation then went through the House of Commons to start the release of paramilitary prisoners, which began in September 1998. The Labour government proclaimed that the IRA’s ceasefire was not being breached even as they knew that it was (Chapter 6). According to Blair, from the BFA to October 2002 the IRA ‘… were going to wait to see if the Unionists delivered their side of the bargai...