“If I had influence with the good fairy who is supposed to preside over the christening of all children I should ask that her gift to each child in the world be a sense of wonder so indestructible that it would last throughout life, as an unfailing antidote against the boredom and disenchantments of later years, the sterile preoccupation with things that are artificial, the alienation from the sources of our strength.” Rachel Carson , a marine biologist, expressed this wish in “Help Your Child to Wonder,” an unconventional how-to article for Woman’s Home Companion in 1956 (Carson 1965, 42–3). This was at the height of her celebrity career as a natural history writer, at the very moment she was turning to a more direct conservation politics and the writing of Silent Spring, her 1962 book on pesticides and the industrial degradation of the environment that would help turn environmentalism into a widespread movement. The importance of wonder, and the help we might need to experience it, she continued to think urgent to these politics. Without wonder at nature, she asked, why would we care about it? And if we fail to care, insulated in a solipsistic dream of human power, we undermine ourselves: “The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us,” she said, “the less taste we shall have for the destruction of our race” (Cafaro 2011). When she died in 1964 she was planning to expand the earlier article into her next book, to be called A Sense of Wonder. No doubt environmentalists since Carson have felt the same ethical urgency of wonder: not as mere logicians or moralists dutifully trundling their principles into nonhuman worlds, but as awed nature enthusiasts who know enchantment to be an inspiring, ethical force.1

Not only does nature at large—the wild and various otherness of the cosmos—both need and inspire our wonder. Philosophers have argued that wonder is a cornerstone, too, in our intellectual openness to and empathic appreciation of human differences; as such, it may even be important to good citizenship.2 Jane Bennett has given this ethical argument its broadest expression by arguing that we need to “love life” in order to “care about anything,” and that a disenchanted world ranges its forces against such affective attachments (2001, 4). The stakes are set high, then, for how our world understands wonder. But is it, after all, so very hard to find or to cultivate? If Bennett is right, such enchantment is not only all around us in the natural world, but in our manufactured ones as well—including the world of capitalist commodities and their marketing (114, 128). If that is so, then are we bereft of wonder or are we saturated by it? There is little consensus to be found when it comes to the fate or power of modern wonder. Is it everywhere lost or suppressed? Or does it thrive around us, ignored by scholarly treatises? In either case, what good does it do, or what ill? The answers to these questions depend on pinning down what we mean when we talk about wonder. Its volatility and contradictions, indeed its risks, are problems I will explore in subsequent chapters as I give shape to the need to cultivate reading for wonder in literature and life. The design and manufacturing of wonder to be read, not merely happened upon, are the subject of this book.

Elusive Wonder

The need for a wonder that eludes us, the need to produce wonder, is the effect of an experience of disenchantment that is also a historical artefact. Disenchantment names a set of feelings produced by changes in modern society that cannot be dispelled as the mere gloomy projection of an antimodernist imagination. And the culture industry, from high to low, has not been slow to offer re-enchantments. Nowhere is this promise more iconic than in Disney “magic.” Later in this book, I will distinguish such magic from wonder. Yet Disney movies must have got something right, I think, because they get away with telling the same story over and over again: a legion of dully repetitive, dull-minded cartoon fathers and mothers at first fail to understand their soaring, imaginative, open-hearted cartoon children, then are at last reformed by them. What feels right in all that is simply the persistent, ineradicable difficulty of wonder—not, that is to say, the abject Disney parent who conveniently localizes this difficulty, ready for easy reform, but rather the way this human type keeps popping up again, never any wiser, as do audiences for it young and old, requiring a timeless march of exceptional cartoon children to recall or repair their sense of awe and enchantment. Disney seems to know that we are haunted by this difficulty: a fear of having forgotten or of not having learned yet how to see our world anew, how to reveal in it new fascinations and purposes, and how to make unexpected allies to pursue them. So Disney enchants, and exhorts us to be enchanted. It seems there is no way around it: either we are disenchanted, or we are haunted by a fear of disenchantment, which is not much better.

Literary scholarship seems driven by the same fear of disenchantment and difficulty of wonder. Whether innovative or merely iterative, it never tires of promoting strikingly new perceptions, purposes, and affiliations it discovers in its texts, of claiming to open doors that have been shut from blindness or neglect. In this, we surely do not simply look for bare novelty, or strict social purpose. It goes beyond wanting to be convincing or convinced: almost shamefully, I think, because it is not what we are supposed to be doing—do we not also hope to enchant others, or be enchanted ourselves, with something strangely arresting in words and ideas? So it is that across the culture industries, and perhaps archetypally in tourism, the promise of wonder is today an experience less of spontaneous enchantments than of anticipatory re-enchantments, uniquely modern in temperament. For better or worse, the book you are reading unabashedly shares in these feelings and aims.

When I personally think of wonder, however, I am less likely to recall the last scholarly article I read (or, to satisfy Aristotle, the last tragedy I attended) than the last ice cream I lingered over. The age of calculating capitalist industrialism may have disenchanted me, as Max Weber ’s notorious, darkly spellbinding words proclaim, but it has also made possible, for example, the industrial apotheosis of a food that is almost unthinkably strange and pleasurable: cow’s milk, sometimes chicken eggs, some form of sugar, tormented together until they transform into a unified, soft, smooth solid. The taste is wonderful, and not without a cognitive aura: pleasure with a mix-in of awe. How peculiar that we eat it frozen, like virtually nothing else. In “The Emperor of Ice-Cream,” a poem he once declared his favorite , Wallace Stevens thought this sublimely artificial, darkly laborious, ephemerally pleasurable food an image of life itself, which is to say, of life’s mortal beauties and powers: “The only emperor is the emperor of ice cream” (Stevens 1997, 50). In 1922 he could describe ice cream being made by hand for immediate enjoyment; he could not foresee that nearly a hundred years later, ice cream would be mass produced from products we hardly understand, in factories most of us never see, cross vast distances in mobile mechanical freezers, and be stored indefinitely in glowing, rimed recesses in our homes. Its peculiar sovereignty and wonder, along with that of the poem, change and deepen. While ice cream is not normally reflected upon this way, I believe that we can feel it. It is not the same feeling I get from Disney magic , though they are kindred enchantments, both waking me up to my world in an unexpected way, yet both difficult to sustain in that very world. Ice cream, like comics or the personification of animal s , resists being taken seriously by a modern idea of adulthood. These all bear the mark of childish things, of indulgences. So does wonder. Disney , of course, knows that too.

Primitivist Wonder

How is it that wonder has

fallen among the lost illusions and unserious intensities of a grown-up world, of a disenchanted maturity that takes on its duties in modern life? This idea of disenchantment

has various roots, but in the midst of the Great War, it found its most famous expression in Max

Weber’s university address to youth choosing their adult careers. In the world in which they were preparing to take their part, he said, “there are no mysterious incalculable forces that come into play… one can, in principle, master all things by calculation. This means that the world is disenchanted. One need no longer have recourse to magical means in order to master or implore the spirits, as did the savage, for whom such mysterious powers existed. Technical means and calculations perform the service.”

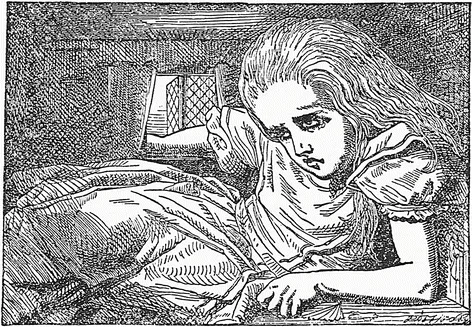

3 Such disenchantment risks turning social life into a grim iron cage of rationalized efficiency. When Alice

finds herself “grown up” in Wonderland, it is in a constrictive, blandly domestic room from which “there seemed to be no sort of chance of her ever getting out” (Carroll

1960, 58–9; see Fig.

1.1). Being trapped there prompts Alice to recall her own disenchantment, even as a child: “When I used to read fairy tales, I fancied that kind of thing never happened, and now here I am in the middle of one!” Wonderland enchants by balefully literalizing a disenchanted growing up, but also by undoing its inevitability. “‘I’m grown up now,’ she added in a sorrowful tone: ‘at least there’s no room to grow up any more

here,’” she suddenly asserts, allowing that maturity may take other, unforeseen paths in Wonderland. It is this feeling

of re-enchantment rather than enchantment, one unmoored from dependable faiths and forms, to which Alice offers the guidance of a modern child.

Disenchantment and re-enchantment are flipsides

of each other. Rita Felski

observes that “while Weber sees the world as rationalized in the sense of being robbed of transcendental meaning, he is far from claiming that our engagement with that world is ruled by the iron law of logic,” and “we are still prone to experiences of enchantment” (

2008, 59). Do we not, indeed

, all the more pursue them? Are we not compelled to invent them? “The increasing abstraction

of visual art,” says Fredric Jameson, “proves not only to express

the abstraction of daily life” into capitalist rationalized functions and values, that is, as the abstraction of a pure experience of aesthetic perception from content and situation (

1981, 236–7). For in so doing, modernist art also turns its cage inside out:

It also constitutes a Utopian compensation for everything lost in the process of the development of capitalism—the place of quality in an increasingly quantified world, the place of the archaic and of feeling amid the desacralization of the market system, the place of sheer colour and intensity within the greyness of measurable extension and geometrical abstraction.

Modernist abstraction is both a confined symptom of a disenchanted cultural logic and its liberatory re-enchantment. This emerges from a study of Joseph Conrad’s

literary impressionism, in particular the story of a youth, Jim, rather different from Alice yet no less vulnerable to following rabbit holes into unsuspected worlds.

It is tempting to loiter among these modernist children and their successors to see where they take us. But I will only ask why these guides are children—or, more broadly, why modern wonder is infantilized or otherwise thought primitive (Weber’s “savage,” Jameson’s “archaic”). This may have a developmental psychology explanation in the association of wonder with novel experiences, since those play such a large role in childhood; and to some extent it must also have roots in Romanticism , which gave us “the child as the paradigm for a renewed vision” (Vasalou 2015, 88, 113). I would like to sketch out, in addition to these, three core ideological...