The Classical Paradigm

Why do certain things have value or price and are not free as air? The classical economists thought it prudent to distinguish between two kinds of goods that are not free: one is fixed in supply and the other can be increased or reproduced. They thought that the goods that are fixed in supply do not play any significant role in the economic life of society. Therefore, they can be left out of consideration of a theory that seeks to explain the phenomenon of price as an aspect of our economic life. As early as 1776, Adam Smith introduced the problem in terms of a rule of exchange between two hunters in ‘the early and rude state of society’:

In the early and rude state of society which precedes both the accumulation of stock and the appropriation of land, the proportion between the quantities of labour necessary for acquiring different objects seems to be the only circumstance which can afford any rule for exchanging them for one another. If among a nation of hunters, for example, it usually cost twice the labour to kill a beaver which it does to kill a deer, one beaver should naturally exchange for or be worth two deer. It is natural that what is usually the produce of two days or two hours labour, should be worth double of what is usually the produce of one day’s or one hour’s labour. (Smith 1981, p. 65)

What Smith does not care to clarify in this relationship, however, is the question of the instruments (or the weapons, in this case) that must have been used to kill the deer and the beaver. If we assume that the two hunters must have used some weapons, however crude, then the question arises: were those weapons made by the hunters themselves or by somebody else? If we assume that the weapons used were fashioned by the respective hunters themselves, then the question arises: did they or did they not need any instruments to fashion those weapons? And if they did need some instruments, then again the question arises: were those instruments produced by the respective hunters themselves or by someone else? And so on. If our answer to this series of questions at every step is that the respective hunters built all the instruments themselves then we must conclude that the whole process of killing the deer and the beaver started with the hunters working against nature with their bare hands to fashion the first instrument without any help from any man-made artefact. Let us start with the assumption that the respective weapons become useless after killing two deer or one beaver, and for the next kill the whole process must start all over again. In this scenario a linear chain of labor-time from scratch to the final production of dead deer and beaver can be laid down and total labor-time spent in their production can be calculated. In the case where weapons remain efficient for killing many deer and many beavers, we will have to devise some rule for depreciating the labor-time from the weapons to the single deer and the single beaver to arrive at the calculation that ‘it usually cost twice the labour to kill a beaver which it does to kill a deer’ (ibid.).

But even after arriving at this calculation our problem is not solved. Since it takes twice the amount of time to kill a beaver that it does to kill a deer, it is obvious that the beaver hunter has to go hungry for twice as long as the deer hunter before he can consume. Thus, if the beaver hunter receives two deer in exchange for his one beaver, then the question arises: why would he not switch to hunting deer and exchanging it for beaver, if he desires to consume some beaver? And since the same logic would hold for all beaver hunters, why would they continue to hunt beaver? The point is that it makes no sense for a group of hunters to specialize in hunting beaver unless there is some reward for going hungry for twice as long as the deer hunters. And any economic reward for going hungry for twice as long would amount to one beaver exchanging against more than two deer. Thus Adam Smith’s simple rule must break down, even in a ‘nation of hunters’.

This is the sort of reasoning that lies at the heart of most of the post-classical (Austrian and neoclassical) critique of classical ‘labor theory of value’ and its proponents’ explanation of the existence of a positive rate of interest in a capitalist system since Nassau Senior (1836). The fundamental feature of such reasoning is its linear narrative. An economic activity has a definite beginning and a definite end. Production of any commodity has a purpose and that purpose is consumption or satisfaction of human desire, which defines the end point. Similarly, production of any good for consumption can be traced back to a point at which laboring activity is unassisted by any produced means of production. In other words, capital investment can be reduced to only wage advances. This identifies a well-defined beginning. Thus in our example of deer and beaver hunters, the beaver hunter must exchange more than two deer for a beaver to compensate for the longer time that it takes to produce a dead beaver starting from scratch than to produce a dead deer. This extra quantity of deer for the extra time is the interest on the extra capital, which is measured by the extra time invested in the beaver industry. Thus capital can be measured by time or the period of production that a productive activity takes from its well-defined beginning to its end.

There is, however, another scenario that may explain Adam Smith’s claim. Because deer and beaver hunting are specialized activities in this ‘nation of hunters’, it may be that weapon making and the instruments that help in making weapons and the instruments that help in making other instruments and so on are all specialized activities. In other words, there is no productive activity that a worker (or a hunter) undertakes that is not assisted by some instrument that has been acquired by exchange from some other specialized worker. In this scenario no one starts from scratch. All the workers and the hunters work for a day (or a year) after which, in the evening market (or the annual market), they exchange their final products with others’ so that what has been used up in production is replenished and the surplus output is consumed (or reinvested) in the mix they mutually desire. In this case no one makes more or less sacrifice than the others, which is their daily (or yearly) labor, and therefore Smith’s simple rule of exchange applies: ‘It is natural that what is usually the produce of two days or two hours labour, should be worth double of what is usually the produce of one day’s or one hour’s labour.’

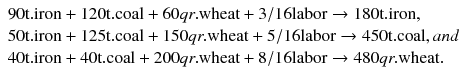

To illustrate this point further, let us take an example from Sraffa (1960) and suppose that there exists a society that produces three commodities in the manner given below:

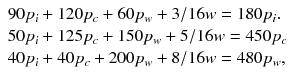

After a production cycle is over, the three workers, or the several workers in the three industries, find themselves in possession of exclusively iron or coal or wheat. To renew the production process for another cycle or the year they must exchange their commodities with each other. What must be the exchange ratios between the three commodities such that the system can reproduce itself? If this society is made of only workers, as Adam Smith’s society of hunters, then all the income generated in this society must be appropriated by the workers. In this case we can write the equations for price determination in this system as:

where p

i , p

c and p

w represent prices or exchange ratios of the respective commodities and

w represents the remuneration of the workers per unit of their labor. By putting any of the

ps equal to one, say p

w = 1, we can solve for the values of p

i, p

c and

w. In this scenario, it turns out that the exchange ratios between iron, coal and wheat—that is, p

i : p

c : p

w—must be in proportion to the labor contents of one 1 ton of iron: 1 ton of coal: 1 qr. of wheat. The value of total

w must be equal to the value of 165 tons of coal plus 70 quarters of wheat, that is, exactly the total value of the net output of the system. Thus Adam Smith’s proposition regarding income and prices in a nation of hunters is completely satisfied. The point to note here is that the prices in this scenario are completely determined by the specification of how net output or total net income is distributed. Once we specify that all the workers must receive equal pay for equal direct labor-time spent in production, which exhausts the total net output, it leaves no room for any psychological factor such as the initial sacrifices made to acquire the original means of production to be brought into the picture.

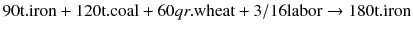

This scenario is

circular in contrast to the earlier

linear one. In this case there is no definite beginning because reducing any production process to its direct and indirect labor will always leave some

commodity residue. For example, we can collect direct and indirect labor in the production of iron given by

by replacing 90 tons of iron by (45 t . iron + 60 t . coal + 30 qr . wheat + 3/32 labor) and then again replacing 45 tons of iron by (22.5 t . iron + 30 t . coal + 15 qr . wheat + 3/64 labor) and so on. By making similar substitutions for 120t.coal and 60qr. wheat, we can see that the quantities of commodities, iron, coal and wheat, become successively smaller and smaller. By reducing the commodity residue to negligible levels we could calculate the total direct and indirect labor-time embodied in a commodity, although the commodity residue never completely vanishes. Therefore, there is no well-defined ‘beginning’ of the production process. One serious implication of this is that, even if wages become zero, there is a finite maximum to the rate of profits beyond which it cannot rise because there will always be some positive capital in the form of materials or produced means of production. However, in the linear scenario, since all capital can be reduced to wage advances only, the rate of profits must rise to infinity when wages become zero. Furthermore, there is no definite end to an economic process in the circular scenario—production merges into reproduction. There is no hierarchy of goods of ‘lower order’ or ‘higher order’ or ‘consumption’ and ‘intermediate’ goods in the process of production. And finally, the exchange ratios or prices of commodities are explained solely on the basis of

objective data.

This is what Sraffa (1960) refers to as the ‘classical standpoint from Adam Smith to Ricardo’ in the ‘Preface’ to his book. It should, however, be kept in mind that this is a reconstruction of the classical standpoint by Sraffa. Both Adam Smith and Ricardo were interested in finding the ultimate cause of changes, whether in the wealth of a nation or the distribution of income over a period of time, and thought that they could locate the sole cause of such changes by reducing production to the primordial relation of man and nature. In this context they did try to reduce all capital to wages advanced by the capitalists with no commodity residue remaining. As we shall see in Chap. 6, this was Sraffa’s own reading of Smith and Ricardo in summer 1927.

Now, let us get back to Adam Smith’s story. After recounting the ‘natural’ rule of exchange in a society of hunters of deer and beaver, he quickly abandoned his proposition that ‘[i]t is natural that what is usually the produce of two days or two hours labour, should be worth double of what is usually the produce of one day’s or one hour’s labour’ on the grounds that once a class of capitalists and landlords arrive on the scene and ask for a share in the total net output, this simple rule of exchange that is valid for a society of only laborers no longer holds. In other words, the change in the rule to account for the appropriation of the net output demands a change in the rule for exchange of commodities. Ricardo thought that Adam Smith was too quick in abandoning his original proposition.

Ricardo ([1821] 1951) argues that it was a mistake on Adam Smith’s part to have abandoned his original proposition that relative value of commodities are determined by relative direct and indirect labor-time expended on their production when the net output is divided between wages and profits. He showed that, if the ratios of direct to indirect labor-time needed to produce all the commodities are the same, then a positive rate of profits would not affect the exchange ratios of commodities determined on the basis of embodied labor ratios. In other words, the labor-time ratios would predict the correct exchange ratios even if the society was not made up only of laborers but was divided between capitalists and laborers and there were positive profits in the system.1

However, this conclusion would not hold when the ratios of direct to indirect labor of various industries are not uniform, which is the general case. This is because, if wages are lowered by 10%, the total income released to be transferred to the capitalists of each industry would be in proportion to the share of the direct labor employed in that industry however the total capital employed in the industry is measured by the direct plus indirect labor employed in the industry. Therefore, if the ratios of direct to indirect labor-time are not uniform across industries then prices determined by labor-time ratios would generate unequal rate of profits across industries. But Ricardo, following Adam Smith, strongly held the view that such situations cannot hold for long in a competitive capitalist system because movements of capital in search of the maximum rate of profits must lead to a uniform rate of profits across industries in the long run. This can happen only if the price ratios or the exchange ratios of commodities deviate from their labor-time ratios.

Ricardo acknowledged this difficulty but did not think that it was a good enough reason to abandon the ‘labor theory of value’. He argued that the requirement of a uniform rate of profits in the general case only introduces a ‘modification’ to the strict ‘labor theory of value’, but he did not go on to show how these ‘modified’ exchange ratios are determined on the basis of the labor-times embodied in the commodities. Instead, he modified his theoretical stance. He proposed that given the ‘modified’ exchange ratios, whatever they might be, any change in those exchange ratios can be traced back to changes in the total labor-time required to produce the commodities. Thus labor-time is the sole cause that explains changes in the price ratios of commodities.

But this ‘modified’ hypothesis does not solve the original problem. It is clear from our example that prices or exchange ratios must change with changes in wages if the condition of a uniform rate of profits is to be maintained in the general case. So how could Ricardo argue that the sole cause of change in prices is labor-time? In his published book, Ricardo tried to get away from this problem on the grounds that even large changes in the rate of profits or wages have very minor effects (not more than 6–7%) on the prices, so this cause could be practically ignored. However, from his unpublished notes it is clear that he did not think that this was a satisfactory argument. In Sinha (2010a, b) I have argued that Ricardo went on to entertain the idea that the effect of changes in wages on prices is solely due to the fact that we have to arbitrarily choose a commodity as a unit of measure to quantify changes in wages and prices, but no matter which measuring yardstick one chooses it is itself affected by the very changes it is supposed to be measuring. He thought that if one could find an ‘invariable measure of value’, in the sense that the measuring standard would not be affected by changes in wages, then one could show that wage changes have no effect on prices of commodities when they are measured against this measuring standard.

This hypothesis, however, is logically untenable. Suppose that there are three commodities a, b and c that exchange in the proportion 1:2:3 when wages are equal to 1 and the exchange ratio of commodities b and c changes to 2:4 when wages become 0.9. If w...