Following the end of World War II, America became increasingly paranoid about anything remotely foreign or different, with this paranoia focusing itself more and more on political philosophies, such as communism, outside its comfort zone and realm of understanding. This paranoia resulted in the House on Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) begun in 1938, a committee that proved that the climate of hysteria in America at the time could and did lead to the loss of basic freedoms for suspected citizens and others, in what amounted to a twentieth-century witch hunt—one that separated wives and husbands, fathers or mothers from their children, and created a situation in Hollywood that led to the dismissal of actors, directors, writers, producers and others in the film industry. It was amidst this tense environment that Charlie Chaplin and his often naïve-seeming political pronouncements—a behavior he enjoyed and came to seek out more and more after his 1931–1932 world tour—began to result in problems for him in the media and later at the box office. With the last appearance of the Little Tramp persona in either his 1936

Modern Times or 1940

The Great Dictator (there is some contention in regard to this issue, which does not affect this investigation), Chaplin’s American audience began to forget what it was that attracted them to this British filmmaker in the first place, or, as Richard Schickel suggests, a new generation of filmgoers inhabiting cinema seats never experienced the Little Tramp phenomenon firsthand, and so, owed him no loyalty:

1 The feeling of anyone born after, say, 1930 for The Little Fellow is bound to be rather abstract; we simply did not experience the excitement of discovery, that sense of possessing (and being possessed by) The Little Fellow that other generations felt. We knew who he was, of course, and our elders endlessly guaranteed his greatness to us. But he remained something of an abstraction: a figure to be appreciated, of course, but impossible to love in the way he was loved by those who had been present at the creation. 2

Five years after HUAC’s “Blacklist” hearings in 1947, Chaplin would leave America, never to reside there again.

But this was not the end of the story of Chaplin’s Little Tramp and American culture, for in fact, a resurgence of the endearing characterization was bubbling underground all during the postwar period. This investigation of that resurgence has to begin, of course, with Chuck Maland’s seminal Chaplin and American Culture: The Evolution of a Star Image in which he asserts that: “In the 1960s, particularly between 1960 and 1964, Chaplin’s star image began to take on more positive associations in the United States.” 3 Maland spends an entire chapter, which he entitles “The Exiled Monarch and the Guarded Restoration, 1953–77,” discussing this gradual turning of the tide in America, in a way that strongly suggests, as does this investigation, that Chaplin and his Little Tramp emerge at the end of this period having finessed a re-invigoration of his star image, “one much more positive, which emphasized Chaplin the virtuoso filmmaker and aging family patriarch, as well as, once again, the adorable Charlie.” 4 My current investigation intends only to build upon the apparatus Maland has already constructed, not to destroy, change or undermine it. However, I will respectfully suggest here that Chaplin’s restoration—the resurgence of his Little Tramp persona—had begun several years before this time period (at least by 1947) and amidst the upheaval surrounding Chaplin’s politics. The Beat generation poets and their immediate forebears, the Bohemians, along with film screenings—both legal and illegal—a surge in Chaplin merchandising that included news coverage, biographies, and products bearing the copyrighted image, all contributed in this re-vitalization of the Little Tramp figure, thereby solidifying him once and for all in the minds and hearts of Americans as an important icon of American culture still recognized today.

Chaplin’s Farewell to the Little Tramp

Charlie Chaplin describes his intentions and motivations behind this character in his 1964 autobiography: “I wanted everything a contradiction: the pants baggy, the coat tight, the hat small and the shoes large […]. You know this fellow is many-sided, a tramp, a gentleman, a poet, a dreamer, a lonely fellow, always hopeful of romance and adventure.”

5 Members of his audience, such as Wyndham Lewis, viewed the character as “always the little-fellow-put-upon—the naïf, child-like individual, bullied by the massive brutes by whom he was surrounded, yet whom he invariably vanquished.”

6 A. G. Gardiner, in his book

Portraits and Portents (1926) notes that Chaplin “comes into the great, big, bullying world like a visitor out of fairy land, a small, shuffling figure, grotesque yet wistful, a man yet a child, a simpleton who outwits the cunning, moving through an atmosphere of the wildest farce, yet touching everything with just that suggestion of emotion and seriousness that keeps the balance true. He is in the world but not of it, and the sense of his aloofness and loneliness is emphasized by the queer automatic actions that suggest a spritelike intelligence informing a mechanical doll” (Fig.

1.1).

7 Also worth noting here, and something I devote more energy to in my introduction to Chaplin’s 1933–1934 travelogue A Comedian Sees the World, is the phenomenon of the film-viewing public’s frequent conflation of Chaplin the man with his Little Tramp persona. When word got out that Chaplin was to appear somewhere in person, the public thronged to see him, but expected to find his mustachioed, esoterically dressed but loveable tramp—and were always disappointed in that regard. However, in his publicity materials, Chaplin and his publicists took advantage of this propensity in his public to conflate the two “characters” and capitalized upon that whenever possible. Clearly, Chaplin’s public post-1952 possessed this same propensity—one that facilitated his quick resurgence during the period.

In many ways, the innocence of the Little Tramp persona, though, made it difficult for Chaplin to return to him after his 1931–1932 world tour—a tour arranged to promote the silent City Lights (1931) several years after the onset of sound technology in film, but also a tour that changed Chaplin’s relationship with politics that would shortly change his art as well. This situation suggests that, in fact, Modern Times (1936), Chaplin’s first film after his return from the tour and essentially another silent, was his farewell to the familiar persona. Its gags are gags from other beloved Chaplin films: the skating scene from The Rink (1917), the escalator scene from The Floorwalker (1916) and the café scene from both Caught in a Cabaret (1914) and again The Rink (1917), just to name a few. It is the first Little Tramp film in which he meets a friend, Paulette Goddard’s Gamin, and leaves the film in his/her company. Others believe the goodbye to the Little Tramp begun in Modern Times, then, is completed in Chaplin’s first talking picture, The Great Dictator (1940), which features dual characters, the Jewish barber and Adenoid Hynkel, both of whom look like Chaplin’s familiar characterization. The Jewish barber’s speech at the end of the film is as much Chaplin’s own 8 as the character’s, and, consequently, it becomes the final pronouncement for that character and everything Chaplin himself has attempted to make of him. 9 The end of the speech—the end of the film—can be considered the swan song of the Little Tramp. In accordance with this theory, the release of The Great Dictator on March 17, 1941 marks his assumed date of death, for Chaplin never returned to him.

Chaplin in America, 1941–1952

After Chaplin’s abandonment of the Little Tramp persona, he spent a tumultuous last ten years in America. President Roosevelt asked him to give

The Great Dictator speech at a Constitution Hall event the night before his third inauguration, January 19, 1941, then later the same year for the DAR, also in Washington, DC, for a radio spot.

10 He soon found himself in trouble due to the mental instability of an actress he considered for the lead role in an abandoned film project of the play

Shadow and Substance. Chaplin, however, continued to rankle the ire of the American public and its government by openly promoting his far-left politics.

11 His speech for the Artists’ Front to Win the War, given on October 16, 1942 at Carnegie Hall, contained a host of quotable elements, still oft-referenced today, such as “Any people who can fight as the Russian people are fighting now […] it is a pleasure and a privilege to call them comrades,”

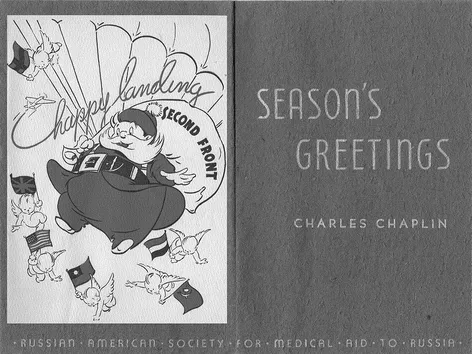

12 and “I don’t need citizenship papers. I have never had patriotism in that sense for any country, for I am patriotic to humanity as a whole. I am a citizen of the world” (Fig.

1.2).

13 Then on December 16, 1942, Chaplin took part in a radio broadcast of Robert Arden’s

America Looks Abroad, with other panelists, including biographer Emil Ludwig, actors Nigel Bruce and Sir Cedric Hardwicke, and director Frank Lloyd. Chaplin’s participation is passionate, especially in his defense of Russia. At one point, he remarks with fervor:

While people are anti-Communist, I’m going to be Communistic. I’m going to be pro-Communist, in other words. I’m not a Communist—I’m not anything, but when I see there are people who are deliberately trying to divide this country, they’ve used the bugaboo—Hitler used the bugaboo of Communism in order to get the Allies to fight on his side against Russia. We didn’t fall for that. No.