The introduction of the euro has had profound consequences for the economies of Europe. Why the introduction of the euro has caused such a widespread economic distress has hardly been recognised in macroeconomic textbooks or by policy makers within the EU system. The gravest consequences have been for the European Monetary Union (EMU) although, since 2010, the negative impact of monetary union has depressed the European Union (EU) as a whole. However, a genuine catastrophe has befallen those countries in the Eurozone, which experienced a substantial balance-of-payments deficit and accumulating foreign debt in the years leading up to the financial crisis of 2008. Suddenly they found themselves in a money trap without access to liquidity. They realised the hard way that they had lost their monetary and financial sovereignty.

These Eurozone countries are still far below their previous level of GDP and have experienced an unbearably high rate of unemployment and social stress.

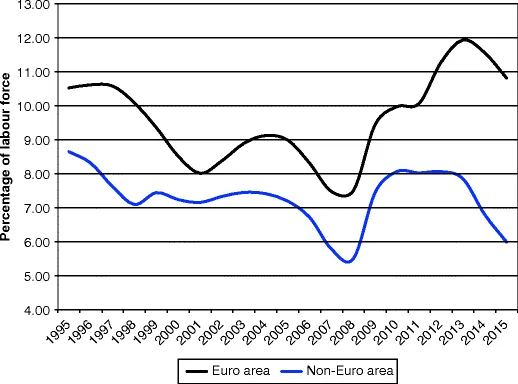

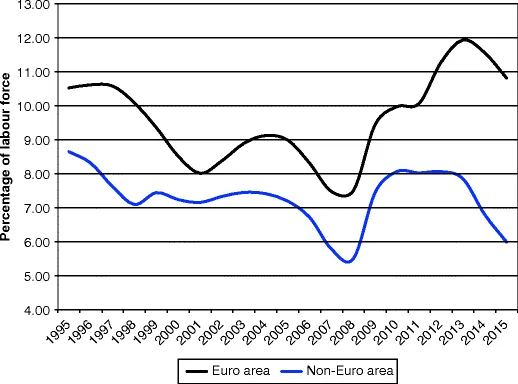

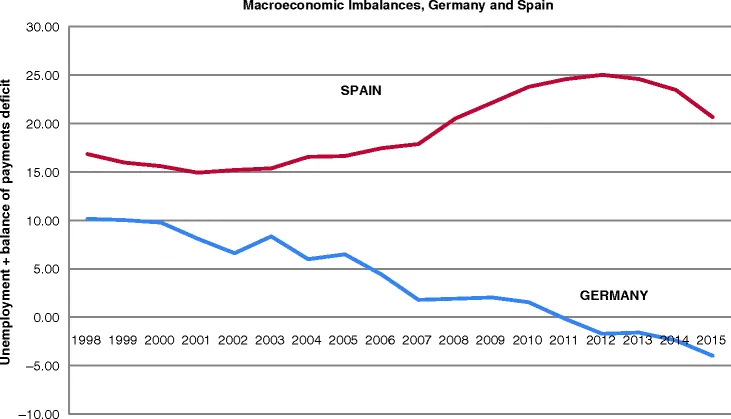

The symptoms of the economic disease of a malfunctioning monetary union are straightforward to diagnose. Stagnating production and increased unemployment in the Eurozone are to be considered as problems affecting the EU as a whole. However, within the Eurozone, these developments have been very unevenly distributed. Those countries with a weak balance of payments – Greece, Spain, Portugal and Cypress – have experienced a steep rise in unemployment. In contrast, Germany, Austria and the Netherlands have, together with a number of non-Euro countries, seen a fall in unemployment and reasonable growth rates after 2010.

Official explanations as to why southern European countries have failed primarily point to public sector deficits and debt, together with inflexible labour markets. EU economists in and around Brussels (and Berlin), which Chap. 2 will characterise more precisely, have largely discarded factors not related to public sector finances as the main reasons for macroeconomic imbalances. When the institutional working rules of the Eurozone were established, the focus was confined to public finances. The so-called Growth and Stability Pact agreed in 1996 focused on public sector deficits as the only major obstacle to a well-functioning European Monetary Union. Upon the advice of EU economists, the European Council decided that public deficits should never exceed 3 per cent of GDP, except in the unlikely case of recession. However, no one could explain where this number – 3 per cent of GDP – came from. Furthermore, no one could explain convincingly why it should be the same for all EU countries, particularly if one considers the eye-catching structural as well as welfare state differences that exist between the EU countries.

On the contrary, not a single word was mentioned in the institutional framework with regard to putting a limit to balance-of-payments imbalances, not even in the macroeconomic convergence criteria which countries have had to fulfil in order to become members of the Eurozone. Quite the opposite, EU economists argued that when Eurozone countries adopt the same currency, the balance-of-payments problem would cease to be a macroeconomic problem. Reality has demonstrated that they were entirely wrong. However, it is a fact which is still waiting to be recognised in textbooks giving the theoretical foundation of the European Monetary Union, see for instance De Grauwe (11th ed.) (2016). From their perspective, it is still mainly a matter of balancing the public sector and setting up a federal political structure. They do not accept balance-of-payments imbalances caused by the premature introduction of the euro as causing high unemployment, stagnating European economy and hereby increased pressures on public finance. In most textbooks, unemployment is caused mainly, if not solely, by the lack of labour market flexibility (i.e. money wages and/or migration). In fact, public sector welfare expenses are seen as obstructions to much needed and necessary labour market adjustments in countries with high unemployment.

This book is concerned with real-world economic problems; notably, problems in the Eurozone that arise when politicians are advised (and misled) by economists, who work with macroeconomic theories and models which are detached from reality. In addition, some of these economists do distrust the ability of the democratic political system to make ‘prudent’ decisions, owing to politicians’ short-sightedness and emphasis on their re-election rather than undertaking responsibility for the process of European integration. Without hesitation, these economists have recommended that, for instance, the board of directors of the European Central Bank should be absolutely independent of the political system. They also fully supported the request of Greece and Italy to be governed, for a while, by a technocrat government headed by a former EU economist (Fig.

1.1).

In this book, in order to demonstrate how and why the Eurozone is in disarray, I look more closely at the Eurozone as a whole and compare its macroeconomic developments with developments in EU countries that have kept their own currency. In addition, I take a closer look at the development within the Eurozone with a main focus on the four largest countries: Germany, France, Italy and Spain. My plan here is to demonstrate that, first, the Eurozone is not in any reasonable understanding of the words an Optimal Currency Area, which has created tensions among the member states, and second, that policy recommendations and request by creditors have enlarged the intra-Eurozone macroeconomic imbalances at a scale which is without any historical precedent over the past 70 years.

Hence, I intend to demonstrate how doubtful many of the high-profile macroeconomic diagnoses have proved to having been derived from an unrealistic economic theory which recommends a sole focus on public sector deficit in order to re-balance the Eurozone. By disregarding other important macroeconomic imbalances and policy instruments outside their policy concern and recommendations, EU economists have derailed the entire Eurozone project to such an extent that the Eurozone itself has been at risk of falling apart. This possibility of collapse was, indeed, openly discussed over the summer of 2015, although it was pushed aside by the Greek government submitting to the requirements of EU economists headed by the EU Commission, the ECB and the IMF.

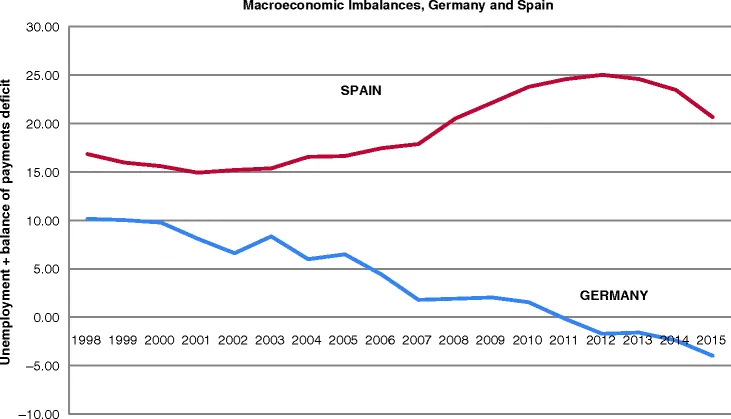

Until 2007, Spain had a balanced budget and even a surplus for a few years, whereas Germany had considerable deficits, which even exceeded the EU-imposed limit of 3 percent of GDP. Germany was then asked by the EU Commission to save on public finances even though the rate of unemployment was close to 10 percent just after the turn of the century. In contrast, Spain was growing quite fast as a consequence of a low level of interest and a private sector building boom. Spain was praised and Germany blamed, whereas the opposite should have been the case considering that when the financial crisis hit Spain, the housing bubble burst and private banks were brought to or beyond the brink of bankruptcy. Moreover, unemployment rose steeply and public finances were burdened by huge social expenditures and a number of bank rescue packages. On the other hand, Germany has benefited from having had the lowest wage inflation amongst all the Eurozone countries for several years, which has made a significant contribution to Germany’s international competitiveness, particularly in terms of boosting exports to the other Euro countries and to the emerging economies.

In the years leading up to the crisis, Germany was therefore becoming the heavyweight within the Eurozone. Nonetheless, within a few years, the German government’s budget deficit was at stake in contravening the 3 percent budget rule of the Stability Pact. Instead of realising that the institutional set-up was wanting and countries were still divergent, the German chancellor just begged for a special case exemption from the European Council. At the same time, the Spanish economy was heading along at relatively high growth rates, with expanding employment caused by a private sector building boom and a growing balance-of-payments deficit. However, the EU economists did not care about these private sector imbalances as long as the public sector budget was balanced. On the contrary, Spain was used as an example to demonstrate the positive impact of introducing the euro and an argument for more EU countries to join the Eurozone. However, when the crisis hit in 2008, Spain was much harder hit by the crisis in terms of rising unemployment due to the huge balance-of-payments deficits and foreign debt, which could not be financed.

The important role of the balance of payments for macroeconomic stability is the main concern of this book. The difference in development after 2008 between the two just-mentioned countries shows how misleading this blinkered focus on public sector budgets has proved to be with regard to understanding the real underlying macroeconomic imbalances that reduce countries’ resilience when a crisis hits (Fig.

1.2).

Why has the Euro failed? The answers are manifold and provide the main content of this book. Of course, there is no single answer; I should rather say that the failure is the sum of a number of misguided decisions initiated by a group of politicians, economists and civil servants close to Brussels during the 1990s and early 2000s when European integration and de-regulation of the national and European economies were high on the political agenda. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the Iron Curtain in Europe gave strong political and ideological momentum to neoliberalism and European market integration. The phrases More Europe and More market became more or less synonymous. Here, one (European) currency came to be seen as an instrument to promote both ideas. Hence, the next step in the message coming from Brussels was to proclaim One Market, One Money – which sounded almost trivial. The populist argument is that you save exchange costs when travelling or trading across borders and a common currency makes it easier to compare prices within Europe. Both arguments are of course true, but it is a fact you don’t need a university degree in economics to understand, and only represent a small part of the larger picture. So, if the macroeconomic consequences are left aside, then the presentation is lopsided.

The macroeconomic arguments have unquestionably become the most pressing; but they are also, admittedly, the most difficult to understand and explain unless you argue from a general equilibrium perspective. Realist macroeconomics arguments have to address the characteristics of the economic structures and traditions of the participation economies with regard to welfare state, productivity, labour market organisations and banking and financial sectors. What does it mean to give up important national policy instruments when the macroeconomic future is uncertain and the adjustments pattern to external (and internal) shocks are quite different? And what happens if there is no formal agreement among the participation countries within the Eurozone to support each other when countries are hit differently and yet they have accepted giving up their national money, their specific exchange rate, and have to adjust to strict limits to the public sector budget, that is, fiscal policy? These questions posed by realist macroeconomists were, unfortunately, not addressed when the EMU was designed.

However, expectations were high in the wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the Euro was presented as one more step in the inevitable movement towards an ‘ever closer union’ bringing prosperity to all Europeans. This has evidently not happened. Expectations were not fulfilled and an increasing number of Europeans are today becoming sceptical towards the European project in the present form without prosperity.

This book explains why the monetary union, the stability pact and the euro together have caught a number of Euro countries in a macroeconomic trap causing a social collapse, which the hardest hit countries cannot get out of by their own means. They are no longer in command of their own economic destiny.

Accordingly, it is hardly an exaggeration to claim that the euro has failed. It might not disappear entirely. The future of the euro will be decided in Berlin and Brussels, in what form no one can say today, but hopefully through a more democratic process than hitherto and with the guidance of euro-realists to prevent the EU from falling apart.

Bibliography

De Grauwe, P. (2016). Economics of monetary union (11th edn.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.