eBook - ePub

Paratexts and Performance in the Novels of Junot Díaz and Sandra Cisneros

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Paratexts and Performance in the Novels of Junot Díaz and Sandra Cisneros

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Part of a new phase of post-1960s U.S. Latino literature, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Díaz and Caramelo by Sandra Cisneros both engage in unique networks of paratexts that center on the performance of latinidad. Here, Ellen McCracken re-envisions Gérard Genette's paratexts for the present day, arguing that the Internet increases the range, authorship, and reach of the paratextual portals and that they constitute a key element of the creative process of Latino literary production in 21st century America. This smart and useful book examines how both novelists interact with the interplay of populist and hegemonic multiculturalism and allows new points of entry into these novels.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Paratexts and Performance in the Novels of Junot Díaz and Sandra Cisneros by Ellen McCracken in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Critique littéraire moderne. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

LittératureSubtopic

Critique littéraire moderne1

Epitextual and Peritextual Portals to The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

Abstract: A constellation of epitexts (paratexts not materially attached to the book) is created by the author, publisher, and the public. At various stages of reading, people encounter interviews, and social media posts by Díaz that interact with and shape understanding of the novel. In the age of Web 2.0, readers themselves also write about the book in broad public venues. Crowd-sourced annotations online explain Díaz’s allusions. Blogs and a wide range of non-authorial commentary, reviews, and discussions about the novel online are new epitexts that overlay Oscar Wao in the digital age. Attached to the book are key allographic peritexts. These peritextual portals such as the front cover, interior graphics, formatting, and alterations in the digital version affect interpretation and are largely outside authorial control..

McCracken, Ellen. Paratexts and Performance in the Novels of Junot Díaz and Sandra Cisneros. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. DOI: 10.1057/9781137603609.0005.

Early on in his career, American writer Jimmy Santiago Baca was invited to meet with powerful literary agent Susan Bergholz in New York City to discuss signing with her. He listened to her grand plans to market him as a Latino writer at this key moment in American history when minority groups demanded inclusion on their own terms into the American literary canon. As I have argued, one result of the militant movements of ethnic and racial minorities of pride and self-assertion in the 1960s and 1970s was American capitalism’s attempts to profit from these groups. Mainstream US publishers, for example, began snapping up the new writing, especially that of women, and marketed them as ethnic and racial commodities. This phenomenon is an important part of hegemonic multiculturalism—a system of material and ideological practices that attempts to contain and profit from the populist multiculturalism that arose in the 1960s and 1970s during the Chicano and Black Power Movements.

Jimmy Santiago Baca turned Bergholz’s proposals down. “I did not want to be boxed and marketed in this way,” he recounts. Instead, he rose to renown in the American literary canon without such marketing, and attained international recognition, with his books translated into 31 languages. Japanese visitors sit outside the Albuquerque house he rebuilt after it burned, described in his poem “Meditations on the South Valley,” and point to lines from the poem that correlate to the house.1 After sending the noted American poet Denise Levertov his poems written in prison, Baca rose to the top on the strength of his writing, published by New Directions, Grove Press, and Heinemann. He did not escape the social forces of multiculturalism from above but he chose not to strategically insert himself into this milieu as a marketing device.

In contrast, as we will see in Chapter 3, from the start Bergholz and Random House marketed top Chicana writer Sandra Cisneros as a postmodern ethnic commodity. A superb writer, Cisneros may well have risen to the top on her own, as did Baca, without the ethnic marketing. Both writers now command $10,000 for speaking engagements and make six-figure incomes from book royalties. In contrast to Baca’s stark black-and-white self-presentation, Cisneros performs ethnicity with bright colors and ethnic images such as Virgin of Guadalupe jewelry and clothing and a “Budda-lupe” tattoo. Where many of Baca’s covers have black-and-white images, Cisneros’s are always brightly colored.

Regardless of the style of marketing, however, both writers and their texts are inescapably imbricated with the often stereotypical images of Latino ethnicity predominant in American society. Whether deliberate and intentional as in Cisneros’s case, or secondary to a great poet’s ascension to the American literary canon as in Baca’s case, both publishers and writers create extensive paratextual networks that sometimes play on ethnicity and always change the original text, extending it beyond its borders in new textual formations. And, in addition to the paratexts representing stereotypical latinidad and a generalized ethnic otherness, a further set of evolving paratextual formations shapes US Latino literary writing, causing these texts to be mutable and instable as they interact with the dynamic new paratextual networks that overlay them. Both print and digital versions of these books become mutable texts, changed by the interpretive portals that paratexts create.

Junot Díaz’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007) is one such unstable text shaped by a continuing series of peritexts and epitexts. Some are authorially instigated, others are market based, and still others are constructed by readers. There is intermixture among these categories, and all function to “create” the text in various ways. Both commercial and non-commercial paratexts fundamentally affect markets and circulation patterns as they reconfigure the text to reach a wide variety of consumers. The overtly commercial paratexts constructed by the marketing department of the Penguin subsidiary Riverhead or Amazon’s Author Page contrast readers’ blogs which are written from various motives, usually non-commercial. Díaz’s use of peritexts such as the 33 footnotes in the novel combines with his public epitexts such as interviews and appearances, linking the aesthetic to the commercial. Both types of paratextual formations work to construct writers and their works as postmodern ethnic commodities.

The vast paratextual network that structures and overlays the novel combines elements of hegemonic and populist multiculturalism. Readers are invited to embark on centripetal navigational paths into the novel from external epitexts such as a TV interview or the Amazon webpage. Similarly, they are urged to take centrifugal paths out of the novel to the vast, evolving network of external epitexts such as Goodreads. More than ever, the digital age invites readers to engage in more extensive modes of poaching epitextual artifacts. Although the epitextual fields they navigate as nomads are more extensive than in previous historical periods, readers now have a few more options in which to write their own interpretive epitexts about the novel and upload this material into the immense paratextual network they navigate.

Public autographic epitexts

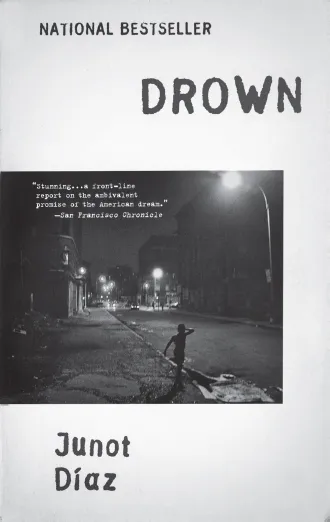

Díaz’s novel is overlain with an especially rich and continually expanding network of exterior paratexts. As the author of Drown, the 1996 collection of sparse, gritty tales about coming of age in the Dominican Republic and the US, Díaz entered the American literary scene as a 27-year-old new Latino voice, dubbed by Newsweek as one of “the new faces of 1996.”2 The dark image on the book’s cover evokes the nation’s larger fear of Latino barrios and syncs with similar stark black-and-white images on the covers of male writers such as Jimmy Santiago Baca.

FIGURE 1.1 Front cover, Drown, Front cover photograph © Ken Schles, courtesy Penguin Random House

The new Dominican-American literary star was reported to have received a six-figure, two-book contract, and later editions of Drown added new advertising paratexts such as the phrase “National Bestseller” above the title, and superimposed the San Francisco Chronicle’s endorsement on the photograph: “Stunning—a front-line report on the ambivalent promise of the American dream.” Drown then functions as part of the paratextual network of Díaz’s 2007 novel, as references to it are embedded in book reviews, ads, and on the front cover of the new book.

Díaz struggled to complete his second book, eventually holing up with fellow writer Francisco Goldman in Mexico City, where the character Oscar Wao came to him as he worked on a longer manuscript about the destruction of New York City by a psychic terrorist. In the last week of December 2000, he published 35 pages of the Oscar Wao material in the New Yorker where he had previously published other stories. Nonetheless, he did not think the subject was “cool” enough and continued writing his Akira fantasy about New York City until reality intervened with the 9/11 terrorist attacks.3

From 2000 on, readers of the New Yorker were situated within a very long paratextual portal written by the author that did not bring them to interpretive negotiation with the full novel until Fall 2007. After having reduced 160 pages of the manuscript in progress to 35 pages for the New Yorker, Díaz then enlarged the novel for six more years. The New Yorker piece is a mini version of the entire plot of the larger novel without footnotes, the extensive sci-fi fantasy allusions, the Dominican history, or the transgressive language. It recounts Oscar’s life in New Jersey from age seven to his violent death in the Dominican Republic in his 20s. While a film preview rapidly intercalates fragments of the movie non-chronologically to entice viewers to pay to see the full film, Díaz’s “preview” of the novel is a capsule version of the entire book that readers engage with for perhaps an hour of concentrated reading. This aesthetic paratext, with its underlying commercial function of selling both the magazine and the future book, whets readers’ appetite, inserting them within a lengthy portal of desire to read the full novel.

While readers of the hardcover novel released in October 2007 approached it through authorial epitextual portals such as Drown, the New Yorker piece, book reviews, and book tour appearances, the novel mutated significantly with the announcement a few months later that it had won the 2008 Pulitzer Prize. Díaz had been positioned within the American literary canon in articles about him that refer to Melville such as “Chasing the Whale” in Poets and Writers (September/October 2007), through the novel’s title which evokes a famous story by Hemingway, and the publication of the preview in the New Yorker. Now, the award of the Pulitzer Prize definitively cemented that position. The publisher quickly introduced a material representation of the prize into the novel’s peritextual artwork. A gold sticker added to the cover with the words “Winner of the 2008 Pulitzer Prize” invites potential readers to engage in a different relationship with the novel’s language and ideas than the previous cover without it. Now, the front cover does not portray the book primarily as an ethnic text with the names “Oscar Wao” and “Junot Díaz,” but as an American mainstream text that won the Pulitzer. Even readers unaware of the news about the prize came into contact with this new paratext of the novel in such mass marketplaces as Costco Warehouses, where the book was displayed face-up with the gold sticker gracing its cover. Are you uninterested in the Dominican Republic or dominicanos in New Jersey? Not familiar with the science fiction and fantasy intertexts in the novel? Not into long footnotes? But it won the Pulitzer! It must be worth reading!

Genette refers to a category of “factual” paratexts such as the author’s age and sex that have an effect on the literary text. However, even such ostensibly straightforward categories need to be nuanced. In a paratextual statement about paratexts like these, Díaz questions his categorization as a “Latino” writer, and touches on the ways in which both hegemonic and populist multiculturalism interact in his work. In a 2008 interview for Slate, he comments on the ways in which his writing floats in between the categories of otherness and Americanness, expressing reservations about those who label him a “Latino writer”:

We’re in a country where white is considered normative; it’s a country where white writers are simply writers, and writers of Latino descent are Latino writers. This is an issue whose roots are deeper than just the publishing community or how an artist wants to self-designate. It’s about the way the U.S. wants to view itself and how it engineers otherness in people of color and, by doing so, props up white privilege. I try to battle the forces that seek to “other” people of color and promote white supremacy. But I also have no interest in being a “writer,” either, shorn from all my connections and communities. I’m a Dominican writer, a writer of African descent, and whether or not anyone else wants to admit it, I know also that Stephen King and Jonathan Franzen are white writers. The problem isn’t in labeling writers by their color or their ethnic group; the problem is that one group organizes things so that everyone else gets these labels but not it. No, not it.4

Here Díaz objects to those who wield the power of labeling and categorization within hegemonic multiculturalism. By constructing labels that “other” him and his writing, they sustain white privilege. It is unfair, he argues that King and Franzen are “white” writers but never referred to as such. Recognizing the inequity that underlies the designation “Latino,” Díaz nonetheless wants to write about Dominican culture and perform his latinidad both textually and extra-textually. He is caught up in the contradictions of American capitalism that insists on class, ethnic, racial, and gender divisions while at the same time celebrating ethnicity and making money from minority writers such as Díaz and Cisneros.

These paratextual statements, along with the Pulitzer Prize, situate Díaz as an American writer whose themes happen to be about Latino history and culture, just as Franzen writes about the American middle class. The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao therefore normalizes the history of the Dominican Republic and diasporic communities in the US as important elements of American history because it is innovative, prizewinning writing, not because it is about ethnic culture. With respect to the paratextual portal the prize opens, many readers buy and read the book not because of its ethnic overlay but because of its canonical status in American literature. Subsequently, th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Epitextual and Peritextual Portals to The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

- 2 Autographic Peritexts and Expanding Footnotes in Dazs Novel

- 3 Navigating Exterior Networks to Caramelo

- 4 Peritextual Thresholds of the Material Print Artifact

- Epilogue

- References

- Index