1.1 Introduction

The US economist and Nobel Prize winner James Tobin once stated: ‘The most difficult issues of political economy are those where goals of efficiency, freedom of choice, and equality conflict’ (Tobin 1970, p. 263). Fiscal policy is one of these issues. It comprises public spending and taxation. In his classic textbook on public finances, Richard Musgrave identified three functions of fiscal policy: allocation, distribution, and stabilisation (Musgrave and Musgrave 1989). Through their spending and revenue, governments influence the state of an economy, its long-run evolution, and the distribution of resources. As we will see in this chapter, population and individual ageing are linked to these three functions, so much so that Lee et al. (2010, p. 80) stated: ‘The projection of population under girds most long term economic projections and certainly all fiscal ones’. For example, the evolution of population ageing is projected to be one of the main drivers of public spending via age-related items, such as health, and to put pressure on long-term fiscal stability and sustainability; in addition, given the age profiles of—especially—labour-related income, economists have studied the case for age-dependent (or age-conditioned) taxes for allocative and distributive reasons.

Public budgets reflect priorities between areas of government and public goods and—in democratic systems—the public opinion and the electorate’s preferences, usually mediating between private economic agents and interest groups. Public budgets also reflect how government spending will be funded, which means that they define a large proportion of the transfers of resources that will take place between the different economic sectors and actors during a given period.

The structure and size of governmental spending as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) have numerous macroeconomic effects, but how the spending is financed and whether the budget is balanced or the government needs to incur in debt to fund part of its spending also matter. In introductory macroeconomic courses, students are taught that switching from raising taxes to incurring in, or increasing, public debt as a means to financing a fiscal deficit increases interest rates, which negatively affects investment and therefore growth prospects, as well as appreciates the local currency, which reduces net exports—though students in courses based on, or including heterodox economic perspectives, may be taught otherwise—see, for example, Wray (2012). Hence, it will not be surprising that fiscal deficits are one of the most hotly debated topics in economic policy. Who pays by how much and when is another topic of dispute among economists—a topic, of course, closely related to the wider discussion about the merits and de-merits of fiscal deficits and public debt. A 2003 report about Germany includes the following caution: ‘The most direct impact of Germany’s aging will be the staggering fiscal cost -the equivalent of an extra 25 percent of payroll in old age benefits on top payroll tax rates that already exceed 40 percent’ (Jackson 2003, p. 3). In 2016, the financial information and analytics firm S&P Global projected that total age-related public expenditures in Germany will increase by 22 per cent in 2050 to over 24 per cent of GDP in contrast to a projected 20.1 per cent for other advanced economies and that its net debt will grow to 149 per cent of GDP in 2050, up from 66 per cent in 2015 if the government does not implement any countervailing reforms (Winnekens 2016).

Two key concerns are the impact of population ageing on the sustainability of public finances and whether the costs of public projects can be passed onto future birth cohorts. There have been more discordant views in the economic profession on this topic than on almost any other issue. For example, regarding public debt, some economists would say that domestic debt (i.e. the portion of total public debt owed to lenders residing in the country) is ‘neutral’ in that taxpayers owe the stock of domestic debt ultimately to themselves, so servicing and cancelling the domestic debt should have no other economic effect than an internal redistribution of resources between economic agents. Other economists beg to differ and predict adverse effects on incentives to invest and work, falling consumer confidence, increasing costs of finance in international financial markets, and so on. Even others endorse the ‘fiscal illusion’ hypothesis, which posits that economic agents systematically underestimate the costs in terms of future taxes that current public debt imposes on them. For some economists and commentators, high levels of domestic indebtedness would pose a worrying threat for the welfare of current and future birth cohorts a menacing nature all the more perilous in the context of population ageing: ‘The growing imbalance between the population of working people and those who are retired threatens to cause a future fiscal crisis in virtually every nation in the industrial world’ (England 2002, p. 9).

Concerning economics and ageing, one potential economic impact of fiscal deficits stands out: whether future birth cohorts will be affected. As Atkinson (

2014, p. 12) noted: ‘Much of the rhetoric of fiscal consolidation is concerned with the national debt as a burden on future generations’. Atkinson added that we pass onto those who come after us not only the stock of the national debt but also pension liabilities, public financial assets, the public infrastructure and real wealth, private wealth, and the state of the environment and the stocks of natural resources. Apart from pension liabilities, the rest of the list is hardly included in discussions on ageing and fiscal matters. For example, generational accounting sets about to measure whether current fiscal policies impose a burden upon future birth cohorts and, if so, by how much and the implications for future cohorts of policy alternatives they could implement to reduce the deficits. In the words of Cardarelli et al. (

2000, pp. F547–F548):

First, how large a fiscal burden does current policy imply for future generations? Second, is fiscal policy sustainable without major additional sacrifices on the part of current or future generations or major cutbacks in government purchases? Third, what alternative policies would suffice to produce generational balance ś a situation in which future generations face the same fiscal burden, as do current generations when adjusted for growth (when measured as a proportion of their lifetime earnings)? Fourth, how would different methods of achieving such balance affect the remaining lifetime fiscal burdens -the generational accounts- of those now alive?

Before we present the generational accounting framework—and hopefully to whet your appetite—it is worth reviewing two related attempts: Laurence Kotlikoff’s fiscal balance rule and the fiscal and generational imbalance measures by Jagadeesh Gokhale and Kent Smetters.

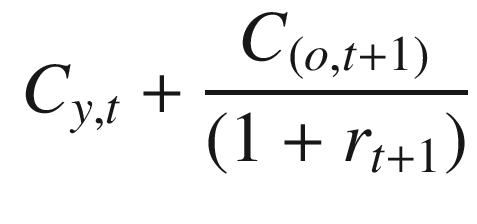

Assume there are two age cohorts, the younger and the older, and that only the former earns an income,

w. First, we consider the case in which the government does not introduce any transfers. The consumption possibilities of the younger age cohort in period

t can be represented by

And the lifetime utility function is assumed to be log-linear

1 :

where 0...

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} U_{t}=\beta\cdot\log[C_{y,t}] + (1-\beta)\cdot\log[C_{(o,t+1)}] {} \end{aligned} $$](OEBPS/images/467741_1_En_1_Chapter/467741_1_En_1_Chapter_TeX_Equ2-plgo-compressed.webp)