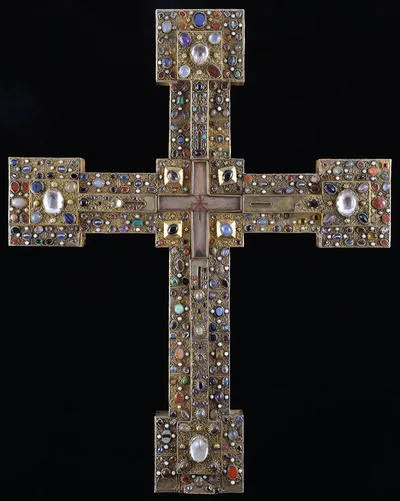

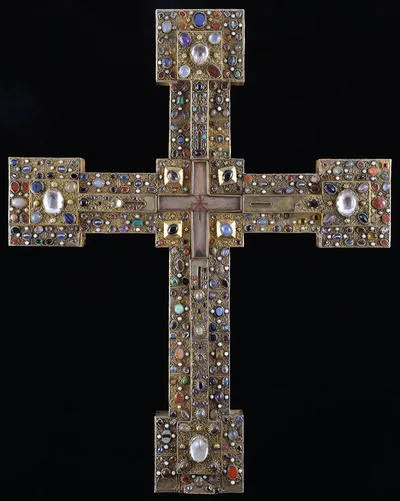

In the museum at the former monastery of St. Paul im Lavanttal in southern Austria there is a splendid piece of Romanesque goldsmith’s work known as the Adelaide Cross (Fig.

1). It is one of the largest

crux gemmata of the eleventh century, and it was originally donated by Adelaide of Rheinfelden, queen of Hungary (d. 1090), to the monastery of St. Blaise in the Black Forest as a memorial to her mother, Adelaide of Savoy (d. 1079.) In the past 900 years, the cross has been altered, copied, destroyed, renovated, and restored. As a result its function and meaning have changed. Nonetheless, a study on an object such as this would allow for a better understanding of the sort of power this mostly unknown queen would have wielded in her lifetime. The lens of object biography would not only elucidate aspects of the turbulent life course of this reliquary cross, but also demonstrate the changing perception of the queen’s agency in its creation in the centuries to come.

1 An analysis of the composition of the gemstones on the cross and a comparison with other similar reliquaries will be undertaken as well. Finally, this long-term view will be employed to see how the meanings related to aspects of the reliquary changed over time. In spite of the limited amount of written data on the life of this particular queen, this approach can clearly demonstrate not only Adelaide’s own imitation of Hungary’s first queen, but also her concern for the promotion of her natal family, particularly their “Roman” or imperial ties. The new questions raised by this approach will aid in understanding issues of gender, memory, and material culture of Central Europe in the Middle Ages.

Regarding the methodology, there is fundamental tension in the archaeological study of the past between the focus on objects versus the focus on people. On the one hand, objects are something that in an archaeological context can be quantified, organized, and analyzed—from this process generalized and abstract conclusions about humanity at large may be drawn. Yet from an interpretive standpoint, this process is one that gives a static, momentary view of the objects and the people that would have interacted with them. For these reasons Chris Gosden and Yvonne Marshall advocated the approach of an object biography which traces the life course of an object through the metaphor of a human biography. What is unique about this approach is that one is able to see not only how humans over time interacted differently with the objects, but how over the course of the object’s life it began to shape the world around it, taking on a life of its own, so to speak. 2 Indeed, objects can have several biographies, be they economic, technical, or social just to name a few. 3 For the study of religious objects and artifacts, this methodology is ideal; most individuals in the Middle Ages were illiterate, and images and objects were almost seen as living, as a liminal connection between this world and the supernatural. 4 Object biography is thus meant to be a more sophisticated analysis that goes beyond merely fabricating a chronology for a particular piece: it is meant to understand, how, as objects change over time, people’s perception of the object changes and the object thus begins to take on new meanings suited to each period.

The Adelaide Cross is perfect testing ground for the object biography due to the combination of surviving written and material evidence. The origin of the Adelaide Cross was documented shortly after her death in the Liber constructionis monasterii ad St. Blasiem. 5 In addition, the gemstones embedded in the Cross are cataloged in eighteenth-century work on the history of the Black Forest (see Appendix I). 6 Admittedly, the donor, Adelaide of Rheinfelden, is not mentioned in any of Hungary’s medieval chronicles, and while she would have issued charters, their existence is only attested to in thirteenth-century royal charters confirming her earlier donations. 7 Even though her husband, Ladislas I (r. 1077–1095), was made into a saint in 1192, she is completely and conspicuously absent in his legends. 8 The barest biographical information establishes that she would have been born sometime after 1060/1061 (the date of her parents’ marriage), married in 1078, and then died in May 1090. 9 Ladislas is known to have had two daughters, presumably from this marriage. One became the wife of a Russian prince named Yaroslav; the other, named Piroska, would take the name Eirene and become the wife of John II Komnenos, emperor of Byzantium. 10 Her father was Rudolf of Rheinfelden, the duke of Swabia, and from 1078 to 1081 a rival to Henry IV for the German crown. Rudolf had previously been married to Henry’s sister Matilda, but after her death, Rudolf married Adelaide of Savoy, sister of Henry’s first wife, Bertha. 11 When Henry IV was briefly separated from Bertha in 1069 and seeking for divorce, Rudolf likewise sought divorce from Adelaide of Savoy, accusing her of being unchaste. She cleared herself of this accusation in the presence of Pope Alexander II and the couple were later reconciled. 12 Written sources are imperative here in the understanding of the Adelaide Cross, but with this approach they are not overtly determining the meaning and function as recorded by those describing it. The picture that emerges from the written sources is that medieval Hungarian queens, as women and foreigners, were easy scapegoats for the chroniclers, and this colors the perception of them to this day. 13 Charters of queens from surviving documents of the Árpád dynasty (1000–1301) only comprise 2 % of the total. 14 The goal here is to examine the life and afterlife of the Adelaide Cross within the context of the agency of Hungarian queens in the eleventh century. This material culture study will be able to prove not only Adelaide’s own program in the design of the cross but also how her own actions recall and reflect those of her predecessors.

The Cross and Its History

In its present state, the Adelaide Cross is 82.9 cm high, 65.4 cm wide, and 7.4–7.8 cm thick. Originally there would have been 170 gemstones adorning the cross, but now there are only 147 stones remaining on the cross. 15 Of the remaining gemstones, there are 24 antique gems and 3 Egyptian scarabs, though in 1783 the total would have been 38 (Ginhart itemizes only 37, see Appendix I). 16 Comparing the list of current gemstones with the itemization of the ones still existing in the eighteenth century, the main difference is the absence of seven lapis lazuli from the current reconstructed cross.

According to the Liber constructionis monasterii ad S. Blasium, Adelaide received a particle of the True Cross from her brother-in-law “Ceysa.” 17 After the death of her mother in 1079, Adelaide commissioned a cross of gold containing the relic to be donated to the Abbey of St. Blaise in the Black Forest along with 70 gold pieces. 18 The Liber constructionis also asserts that Adelaide’s donation was an indication that she wished for the rest of her family to be buried at St. Blaise—this is supported by the fact that her two brothers, Berthold and Otto, were buried at St. Blaise with their mother. The Liber constructionis asserts that the family had a history of donating to the abbey, with many donations coming from her mother (“multas eleemosynas”), and her brother Berthold donating his farms to the abbey. 19 Rudolf of Rheinfelden seems to have taken a personal interest in the Abbey of St. Blaise, in the 1070s implementing Clunaic reforms seen in monasteries like the Fruttuaria abbey in Italy. When Henry IV opposed these reforms, his mother, the Dowager Empress Agnes, mediated between the two, siding with Rudolf and ensuring that the reforms took place. 20 Rudolf is mentioned in the abbey’s necrology and Berthold and Otto built the Nicholas Chapel adjacent to the monastery church between 1092 and 1096. 21 The Adelaide Cross was commissioned under Abbot Giselbert, who served from 1068 to 1086, but it does not seem to have been completed until the tenure of Abbot Uto (1086–1108). 22 According to the Liber Originum, the reliquary cross, it seems, would have originally been a memorial of some kind to her mother, possibly even a grave marker in front of the associated altar. 23 This would be consistent with the family’s interest in the preservation of their memory: after the death of Rudolf, a bronze memorial was commissioned for his grave in Merseburg showing him in a full-sized portrait (one of the earliest German examples) and with the full royal insignia. 24

The second stage of development in the life of the Adelaide Cross would have been in the mid- to late twelfth century under the leadership of Abbot Gunther of St. Blaise (1141–1170). After the monks began to doubt the authenticity of the relic (due to the reliquary’s large size), Gunther was able to prove it and afterward commissioned the back for the cross, which at that point had not been finished. 25 The four points of the cross display the four Gospels and their associated animals. The inscription at the top reads: CLAUDIT(VR) HIC DIGNI CRUCIS ALN ...