![]()

1

Advertising in the Aging Society: Setting the Stage

The motivation for this book is grounded in several reasons. First, older people are of interest in our study because of their rapid increase around the world and specifically in Japanese society, as well as their increasing importance as a market segment (Coulmas, 2007; Kohlbacher & Herstatt, 2011). Siano and associates (2013) argue that “Understanding corporate communication strategy takes on critical importance whenever organisations are threatened by environmental changes … that lead to the redefinition of the role of the organisation in relation to its key stakeholders” (p. 151). Demographic change is such an environmental change that requires responses from corporations (Kohlbacher & Matsuno, 2012). Second, mass media in general and television in particular rank prominently among the major sources of information among older people and are tapped for purchasing and consumption decisions (Kohlbacher, Prieler, & Hagiwara, 2011a; Lumpkin & Festervand, 1988; Phillips & Sternthal, 1977; Smith, Moschis, & Moore, 1985). Third, research around the globe (including Japan) on the representation of older people in television advertising finds them to be underrepresented (Prieler, Kohlbacher, Hagiwara, & Arima, 2015; Simcock & Sudbury, 2006; Y. B. Zhang et al., 2006) and sometimes even to be portrayed negatively or stereotypically (Prieler, Kohlbacher, Hagiwara, & Arima, 2011a; Zhou & Chen, 1992). Such representation has an impact on individual and societal attitudes and perceptions toward older people (Bandura, 2009; Gerbner, 1998; Morgan, Shanahan, & Signorielli, 2009; Pollay, 1986; Shrum, Wyer Jr., & O’Guinn, 1998) as well as toward their consumer behavior (Ferle & Lee, 2003; Moschis, 1987). Last but not least, empirical research on practitioner views/consumer responses to representations of older people is scarce and was conducted many years ago in different cultural contexts (e.g., Festervand & Lumpkin, 1985; Greco, 1988, 1989; Kolbe & Burnett, 1992; Langmeyer, 1984; Szmigin & Carrigan, 2000a). In addition, while there are numerous guides on how to market and target to older people (e.g., Moschis, 1994, 1996; Nyren, 2007; Stroud, 2005; Stroud & Walker, 2013; Tréguer, 2002), there is comparatively little research on the cultural and ethical considerations in using older people in advertising and the media (Featherstone & Wernick, 1995; Harrington, Bielby, & Bardo, 2014; Harwood, 2007; Ylänne, 2012).

This chapter is structured along the lines of the reasons and motivations for the book. In the first part of the chapter, we provide an overview of aging societies around the world and how they affect societies and businesses. The second part of this chapter discusses what challenges and opportunities marketers and advertising practitioners face in this changing marketplace in Japan and shows that Japan can be an excellent case study for other countries that could potentially experience similar developments in the future. In the third part of this chapter we introduce the most common sources of information for older people and then specifically highlight the importance of mass media and advertising in those populations. This is followed by an overview of how the media affects consumer socialization and socialization in general, and thus how it might affect attitudes toward older people. At the end of this chapter, we will discuss explicitly attitudes toward older people in society, with a special focus on Japan.

Aging societies around the world

Population aging on a global scale

Demographic change has emerged as a powerful megatrend affecting a large number of countries around the world. This aging, and in some cases shrinking, of the population has vast overall economic, social, individual, and organizational consequences (Drucker, 2002; Dychtwald & Flower, 1990; Harper, 2014; Kohlbacher & Herstatt, 2011; Magnus, 2009).

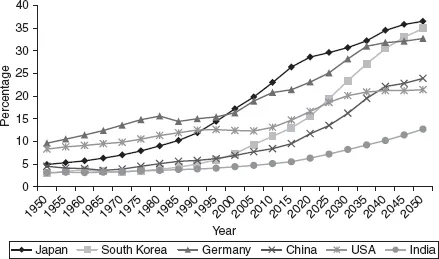

Globally, the number of people aged 65 or over is expected almost to triple, increasing from 530 million in 2010 to 1.5 billion by 2050. In the more developed regions, 16% of the population is already aged 65 years or over and that proportion is projected to reach 25.8% in 2050 (see Figure 1.1). In developed countries as a whole, the number of older people has already equaled the number of children (people under age 15), and by 2050 the number of older people in developed countries will be more than the number of children (25.8% vs. 16.1%). But this trend is not restricted to the developed world. In developing countries as a whole, even though just 5.8% of the population is today aged 65 years or over, that proportion will more than double by 2050, reaching 14.0% that year and 21.0% in 2100 (United Nations Population Division, 2012). We assume these unprecedented trends to heavily affect societies, companies, and politics. We further expect this development to be relevant for industrialized nations as well as for certain emerging economies where aging societies also become an increasingly important issue (Antony, Purwar, Kinra, & Moorthy, 2011; Sasat & Bowers, 2013; N. J. Zhang, Guo, & Zheng, 2012).

Figure 1.1 Percentage of population age 65 or over (middle variant).

Source: Based on the 2012 Population Database of the UN Population Division (2012).

Business implications of the aging society

Against this backdrop, it is all the more surprising to see that research on the implications of the demographic change on societies, industries, and companies is still in its infancy. Most accounts of the so-called demographic “problem” deal, as the term already suggests, with the challenges and threats of the demographic development. These discussions feature, for example, the shrinking workforce, welfare effects, and social conflicts. Academic literature on management is only slowly taking up this challenge, with recent editorials and feature articles calling for more research (Chand & Tung, 2014; Kulik, Ryan, Harper, & George, 2014). In particular, empirically grounded work is missing.

We need to know how companies and whole industries are coping with demographic change. We need to know what the needs of older people are compared to other age groups, and we need to look for practical solutions to their needs. There is also a lack of concepts, processes, and practical solutions in various fields and functions of management: How to segment and approach the market for older people? How to adapt product development, design, and delivery of value to this market? How to grasp the latent needs and wants of the potential older customers? (Kohlbacher, 2011; Kohlbacher, Gudorf, & Herstatt, 2011).

Chances and opportunities are often neglected in the context of demographic change. The emergence of new markets, the potential for innovations, the integration of older people into jobs and workplaces, the joy of active aging, and the varied roles of older people within society are just a few examples of how what at first sight appears to be a crisis could be turned into an opportunity (Kohlbacher, Herstatt, & Levsen, 2015; McCaughan, 2015; Nyren, 2007). All in all, countries and industries are reacting very differently – from still neglecting to proactively looking for and developing solutions (Kohlbacher, 2011; Kohlbacher, Gudorf et al., 2011).

Peter Drucker wrote about the business implications of demographic change as early as 1951 and has repeatedly stressed their importance (Drucker, 1951, 2002). One particularly essential implication of the demographic change is the emergence and constant growth of the “silver market” (Kohlbacher & Herstatt, 2011), the market segment more or less broadly defined as those people aged 50 or 55 and older. Increasing in number and share of the total population while at the same time being relatively well-off, this market segment can be seen as very attractive and promising, although still very underdeveloped in terms of product and service offerings (Kohlbacher, 2011; Kohlbacher, Gudorf et al., 2011).

Marketing scholars already debated the marketing opportunities of the older segment in the 1960s (Goldstein, 1968; Reinecke, 1964). However, despite the growing importance of the older population, older consumers are still under-researched and often not included in a range of marketing and advertising practices (Bartos, 1980; Gunter, 1998; Moschis, 2003, 2012; Sudbury & Simcock, 2009b). This is in contrast to the growing body of research on older consumers’ behavior (Barnhart & Peñaloza, 2013; Lambert-Pandraud & Laurent, 2010; Lambert-Pandraud, Laurent, & Lapersonne, 2005) which provides evidence of age and cohort differences in consumption and suggests that marketers should respond to these accordingly. While executives generally seem to acknowledge the importance of demographic trends, relatively few companies take concrete action to try to develop the older market segment (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2011; Kohlbacher, 2011; Stroud & Walker, 2013) although there are a few notable exceptions (Chand & Tung, 2014; Kohlbacher et al., 2015).

Japan’s aging society

The world’s most aged society

The vast majority of the research on older consumers has been conducted in North America and Europe (Kohlbacher & Chéron, 2012), while Japan, the country most severely affected by demographic change, with a rapidly aging as well as shrinking population (Coulmas, 2007; Coulmas, Conrad, & Schad-Seifert, 2008; Muramatsu & Akiyama, 2011), has been largely neglected. This is astonishing given that older people in Japan hold a disproportionately large amount of personal financial assets. Thus, older people form an attractive market potential. As a consequence, the major Japanese advertising agencies have even set up specialized departments to study older consumers (Dentsu Senior Project, 2007; Hakuhodo Elder Business Suishinshitsu, 2006).

With 26% of its population at 65+ in 2014 (Statistics Japan, 2014b), Japan is the most advanced aging society in the world today, and 87% of Japanese acknowledge aging to be a problem (Pew Research Center, 2014). Japan became an aged society in 1994 – sooner than other industrial nations – when its share of older citizens exceeded 14%. Japan’s share of people over 64 reached 21% in 2007, making it the first country to be labeled a super-aged or hyper-aged society (Coulmas, 2007). As Japan was the first society to experience such dramatic demographic change, its companies were the first to be affected by its consequences and had to adapt their strategies, product lines, and advertising to these new challenges early on.

Predictions indicate that nearly one-third of all Japanese people will be over 64 by 2030 (United Nations Population Division, 2012). At present, 29.0% of women are 65 and older, while the corresponding percentage for men is 23.2% (Statistics Japan, 2014b). Overall, the ratio between the 65+ population and the total population is the highest in Japan, and is forecast to continue increasing and to remain ahead of the rest of the world. No other country has ever experienced such rapid population aging (Clark, Ogawa, Kondo, & Matsukura, 2010).

Shifting markets

Demographic change will also shift market segments. A declining youth segment can be anticipated, in contrast with the continuously growing segment of older people (Kohlbacher, 2011; Kohlbacher & Herstatt, 2011). In fact, many market participants are concerned about the shrinking customer base of young, dynamic buyers as well as the demands of an older target group which are still not very well understood. Demographic change could therefore cause problems for companies that do not adjust their product range and do not address new target groups.

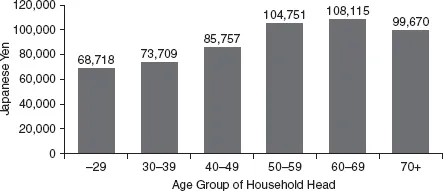

The number of potential customers is not the sole determinant of new business opportunities. Purchasing power and consumer behavior play a significant role and could compensate for the decline in customer numbers (Kohlbacher, 2011). Older people tend to spend their accumulated income and wealth instead of concentrating on savings and investments. Japanese private households with heads aged 50+ spend considerably more money per head than the younger age groups (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Average monthly consumption expenditures per household (by age group of the household head in Japanese yen, 2013 – average spending for one person in two-or-more-person households)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Statistics Japan, 2013.

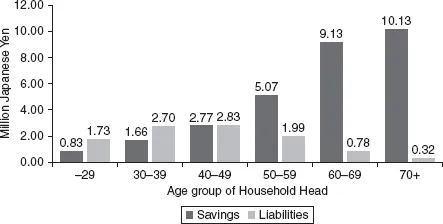

Older people’s high purchasing power also stems from their financial wealth. On average, Japanese households with heads aged 60+ have savings of about 20 million yen. Older people are therefore the top age group in terms of savings. Per person, the generation of people over 70 has savings of more than 10 million yen, closely followed by 60-to-69-year-olds, with 9.1 million yen (see Figure 1.3). As a matter of fact, older people hold a disproportionately large amount of personal financial assets, with those in their 50s and 60s owning 21% and 31% respectively of the total, and those aged 70+ holding 28%. This means that people aged 50+ hold about 80% of the total personal financial assets in Japan (Nikkei Weekly, 2010). Furthermore, the older Japanese generally have nearly no debt and own the property where they live. However, this does not apply to all of Japan’s older people, and the number of poorer older people is expected to rise in the future (Fukawa, 2008; Kohlbacher & Weihrauch, 2009).

Thus the market for older people is seen as a very lucrative market segment. The main focus, at the moment, is on the “old, rich, and healthy”; the “old, poor, and sick” are receiving significantly less attention. There are signs that the market for older people of the future is going to look completely different and that the group of the “old, poor, and sick” could form a clear majority due to: (1) increasing social stratification in general, including issues of precariousness and a widening gap between rich and poor (key word: kakusa shakai = gap society; see for details Hommerich, 2012; Kingston, 2013); (2) the increasing number of people aged 75 and over (this is the age after which physical decline is said to accelerate considerably, and since November 2007 this segment accounts for more than 10% of the Japanese population); and (3) the high number of non-regular employees with insufficient social security (more than one-third of all employees in Japan). As a matter of fact, income and economic inequality as well as poverty among older people are issues of rising concern in Japan (Fukawa, 2008; Ohtake, 2008; Shirahase, 2008). This could become a demographic time bomb and leads to the question of a corporate social responsibility to provide products and services that support seniors in their everyday lives and enable them to grow old in a humane way. Given the right business model, socially and ethically responsible action can also yield economically responsible profits (Kohlbacher & Weihrauch, 2009), not to mention positive reputational effects (see also Kohlbacher, 2011). In this book we focus of course on the current cohorts of older people, but here as well, important implications for corporate social responsibility and marketing ethics can be identified (see also Chapter 6).

Figure 1.3 Average savings and liabilities held per household (by age group of household head in million yen, 2014 – average for one person in household)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Statistics Japan, 2014a.

Segmenting the market for older people

Definitions of the market for older people, the “silver market,” or the “growth market age” vary significantly; it includes people older than 49 or 54 years of age (generation 50+ or 55+) – however, these definitions also include age groups up to the age of 90 to 100. That is, included in this segment are both age groups younger than the baby boomers as well as age groups that are older. While Japan also has adopted the World Health Organization’s definition of “older person” (kōreisha in Japanese) as 65 years or older, this definition was extended to the 50–64 age segment (called shinia = senior in Japanese) by Japanese advertising agencies (Dentsu Senior Project, 2007; Hakuhodo Elder Business Suishinshitsu, 2006) based on the importance of the baby boom generation (dankai sedai: those born between 1947–1949 or 1951 in Japan) who were in their 50s at that time. We have followed in this book this more inclusive definition of older people which is used by Japanese advertising agencies. The 50+ definition is also commonly used in academic advertising and marketing research and in business practices, both in Japan and other countries, though it is by no means a homogeneous market segment (Carrigan & Szmigin, 2000b; Yoon & Powell, 2012).

In order to acknowledge possible differences between the 50–64 and the 65+ age group, we have followed the accepted way of splitting our samples into these age groups. This was confirmed by publications of major Japanese agencies (Dentsu Senior Project, 2007; Hakuhodo, 2003), our interviews and the pre-test, as well as marketing research in Japan (Kohlbacher & Chéron, 2012; Murata, 2012). In many cases, 65 also marks the time of transition int...