The End of the 31st Dáil and the Calling of the Election

At 9:32 am on Wednesday 3 February 2016, the Taoiseach Enda Kenny entered a packed Dáil chamber and without any great fanfare or ceremony announced to the gathered deputies that he was headed to Áras an Uachtaráin to advise the President to dissolve the Dáil. Wishing TDs who were not seeking re-election the best for the future and good luck to those offering themselves to the public again, Kenny was inside the chamber for all of two minutes. Leaving behind an array of disgruntled opposition deputies the Taoiseach then, in that most modern of fashions, took to Twitter to announce that the general election would be held on Friday 26 February. The strapline to his tweet was titled ‘Let’s Keep The Recovery Going.’ 1

While that apparently anodyne phrase would ultimately cause Fine Gael no end of trouble during the subsequent election campaign (see Chapter 4 in particular) it was, to the party’s election gurus, the obvious slogan on which to run its short three-week campaign. After all Fine Gael and Enda Kenny had seen the hated ‘Troika’ of the European Central Bank, European Union (EU) and International Monetary Fund from the country’s shores and were heading up a government that was presiding over a seriously impressive macroeconomic recovery. By the time the election was called Ireland was the fastest growing economy in the EU, which was no inconsiderable achievement after the grim years of austerity that had stalked the Irish landscape and its people since 2008. The trouble for the government would be that not enough people felt the micro effects of the recovery in their own lives, as would become clear during the campaign. In any event, after sending his tweet, which consisted of a video of himself outlining the issues at stake in the forthcoming campaign, Kenny met up with Tánaiste (deputy prime minister) and leader of the Labour Party Joan Burton and together they staged an extremely cumbersome-looking photo opportunity for the media throng that had gathered outside Government Buildings. Kenny quipped to Burton that ‘this is not goodbye’ 2 and hopped into his state car which brought him to Áras an Uachtaráin. Burton was left awkwardly alone to wave the Taoiseach off. She then made a number of brief remarks to the amassed journalists in which she expressed confidence that the government would be re-elected and that Labour, despite numerous poor opinion poll showings, would do well once the votes were cast and counted. After an extremely difficult five years in power this display of togetherness between Kenny and Burton masked considerable tensions between the parties and the leaders themselves. It had all been so different five years earlier.

On nominating Enda Kenny for Taoiseach on 9 March 2011, Fine Gael’s youngest TD, the 24-year-old newly elected deputy for Wicklow Simon Harris, declared: ‘Today, the period of mourning is over for Ireland. Today, we hang out our brightest colours and together, under Deputy Kenny’s leadership, we move forward yet again as a nation.’ 3 As a nod to both the economic catastrophe presided over by Fianna Fáil and the great lost leader of Fine Gael, Michael Collins, Harris’s comments were symptomatic of the bullishness of Fine Gael as it entered office with 76 seats, the largest number it had ever received in its history. 4 It was a similar story with Labour who won a historic 37 seats in the 2011 general election, and after a brief period of negotiation the Fine Gael–Labour coalition, with the largest majority in the history of the state, duly took office on the first day of the 31st Dáil with Enda Kenny elected Taoiseach and Labour leader Éamon Gilmore Tánaiste. Government formation in 2011 was relatively simple because all budgetary decisions and indeed discussions had to be taken within parameters set by the Troika. 5

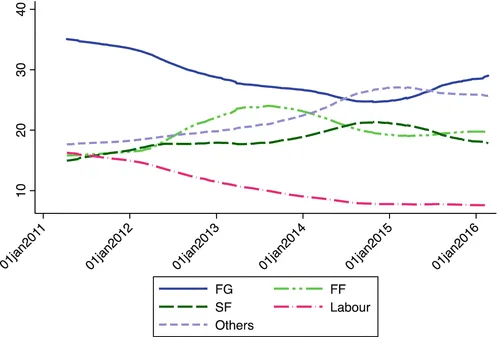

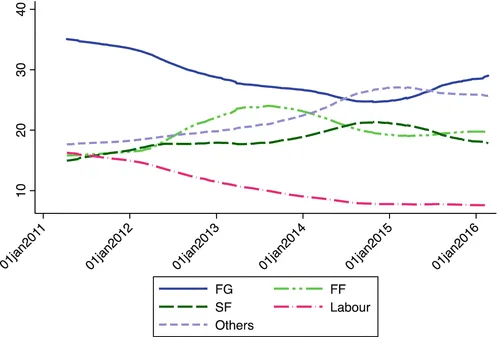

Over the lifetime of the government both parties would suffer significant defections from their ranks and be embroiled in a number of controversies over broken election promises, cronyism and policy-making failure. The five years between elections would see politics in the Irish state become increasingly competitive. As support for both government parties fell throughout the government’s tenure (see Fig.

1.1) and as Fianna Fáil appeared increasingly becalmed, the old certainties long associated with Irish politics seemed destined to disappear for ever. The rise of Sinn Féin, the formation of two new political parties—Renua and the Social Democrats—the increasing assertiveness of previously fringe left-wing groups, principally associated with opposition to water charges, and the seemingly never-ending rise of independents as political alternatives worth voting for, all made the 2016 general election the most difficult to call in modern Irish history. Notwithstanding the resilience of the traditional parties of Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and Labour, it was clear that the combined vote for all three was going to be the lowest in the history of the state. In that context it was almost certain that as the campaign began, government formation would be extremely difficult once the votes were cast. No one, however, could have predicted how difficult.

Party Competition

The result of the February 2011 general election effectively sundered the Irish party system. 6 Three months after the arrival of the Troika to bail out the Irish state Fianna Fáil suffered its worst ever election result, polling only 17 per cent of the first preference vote and winning a historic low 20 seats out of a possible 166. Since it first entered government in 1932 its previous worst result was 65 seats in 1954, while in the May 2007 general election it won 78 seats. Probably best described as a catch-all party since its foundation in 1926, it hovered consistently at above 40 per cent of the vote at election time only dropping to 39 per cent on two occasions, in 1992 and 1997. 7 It had a chameleon-like ability to appeal to all social classes both urban and rural. 8 Once it decided to break one of its core values and enter coalition politics in 1989 with the Progressive Democrats (PDs), Fianna Fáil’s centrist appeal looked like it could enable the party to govern in perpetuity. 9 The PDs in 1989, 1997, 2002 and 2007, Labour in 1992, and the Greens in 2007 had all been persuaded to enter government with Fianna Fáil and it was also skilled at doing deals with independents. Such coalition building was based on the assumption of Fianna Fáil polling around its normal 40 per cent level thus giving it the possibility of choosing alternative coalition partners. After the party’s brutal rejection in 2011 by an electorate which placed the blame almost entirely on it for the austerity that had brought misery across the state this was clearly no longer the case.

The voters in 2011 decided that the best alternative to Fianna Fáil was a Fine Gael–Labour coalition, which they regarded as the most likely to get the country out of the mire of austerity. Neither party had been in power since their 1994–97 ‘rainbow’ coalition government with Democratic Left. The fluid nature of Irish politics in the 1990s was summed up best by the change in government during the 27th Dáil when the Fianna Fáil–Labour government collapsed in November 1994 to be replaced by the partnership of Fine Gael, Labour and Democratic Left. 10 But in 1997 that coalition was itself voted out of office to be replaced by a Fianna Fáil–PD government which would be re-elected twice, the last in 2007 with the help of the Green Party.

While Fine Gael’s success in the 2011 general election might have been seen as inevitable given the collapse in support for Fianna Fáil, it was nevertheless an impressive achievement. This was all the more so given the depths to which Fine Gael had fallen just under a decade earlier in 2002 when it returned with a historically low 31 seats on just over 22 per cent of the vote and its long-term future seemed in grave doubt, particularly as by accepting coalition in 1989 Fianna Fáil opened itself up to alliances that would once have been the sole preserve of Fine Gael. A significant improvement in its fortunes in the 2007 general election where it won 20 extra seats under the leadership of Enda Kenny at least meant that Fine Gael remained relevant in Irish politics. Yet doubts within Fine Gael about Kenny’s leadership saw Richard Bruton mount a ‘heave’ (a leadership challenge) in June 2010 which Kenny, to the surprise of many, successfully rebuffed. 11 Within nine months Kenny was Taoiseach and back in the comfortable surrounds of coalition with the Labour Party.

The result of the 2011 election was a critical juncture for the Labour Party. After a disappointing election in 2007 Labour changed leaders, with the former Democratic Left TD Éamon Gilmore taking the helm from Pat Rabbitte. Gilmore immediately went on the attack in the Dáil, aping the tactics of a previous Labour leader Dick Spring, and proved a vitriolic critic of Fianna Fáil. This culminated in March 2010 when he accused the Taoiseach Brian Cowen of ‘economic treason’ for signing off on the state guarantee of Anglo Irish Bank in September 2008 declaring that the decision had been made ‘not in the best economic interests of the nation but in the best personal interests of those vested interests who I believe the Government was trying to protect on that occasion.’ 12 Unmerciful attacks on Fianna Fáil and full-blooded opposition to austerity had led Labour to a position whereby it had a historic decision to make in 2011 on the back of its greatest electoral achievement. Labour could either go into government with its normal partner Fine Gael or it could stay outside and try to grow further from the opposition benches with a possibility of leading a government after the next election. The dominant view in Labour was that having run a campaign where it promised ‘balanced’ government—that is, that it would provide a check on possible Fine Gael excesses—it could not then remove itself from the responsibility to govern. Moreover most of its leading lights including Gilmore, Rabbitte and Ruairí Quinn were old enough to realise that this might well be their last chance to achieve office. In that context remaining in opposition was never really seriously considered as an option. 13 Labour serenely went into office. It would come out five years later fighting for its very survival.

Part of the reason for Labour’s calamitous period in government was the increased assertiveness of left-wing opposition to the government both inside and outside Dáil Éireann. Sinn Féin was revived after the 2011 general election having increased its strength from 4 seats to 14 and i...