The EU and Its Neighbors

Near the end of November 2013, the then Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych refused to sign the negotiated Association Agreement between his country and the EU at the Eastern Partnership Summit in Vilnius, seeking closer cooperation with Russia instead. His refusal, due to strong pressure from Russia, led to massive public protests on Kyiv Independence Square (Maidan Nezalezhnosti), the events becoming known as Euromaidan. The demonstrations were soon answered by brutal reactions from the state, leading to further complex and violent events. These uprisings were followed by Russia’s annexation of the Crimean Peninsula and the military conflict in eastern Ukraine, which continues at the time of writing. Ukraine’s position between the European Union and Russia has ultimately become clearly evident and very problematic.

That the Ukraine conflict broke out has a great deal to do with how two large political entities, the EU and Russia, perceive their neighbors: Who is a neighbor for whom and what role do they play in terms of the geopolitical positioning of each power? These questions (discussed, for example, in the volumes edited by Freire & Kanet, 2012, and Korosteleva, 2011) will not be dealt with in this book.

However, the fact that the EU appears in its neighborhood as a geopolitical player is the backdrop against which the questions we ask gain in importance.

How can we conduct empirical research on EU’s extra-territorialization? What does empirical research, especially research adopting a micro perspective, reveal about the links between extra-territorialization and security? How does the specific situation in a country impact on the implementation of the extra-territorial engagement?

Our focus is the complexities with which some of the EU’s closest neighbors currently struggle and we are especially interested in the viewpoints that exist in the third countries involved. In order to make plain our interest, first, we will reflect on several central notions: neighbors, the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) and how to frame them in a scientific manner. To this end, we propose the notion of extra-territorial engagement with which the complex interplay between security and integration efforts on the part of the EU can be grasped in a fruitful way. So, in order to address some of the complexities created by how the EU imagines its relations with these countries, we need to remember the point at which the EU began to think in terms of ‘neighbors’ at all. As possibly superficial but still telling evidence that a change in this respect has taken place, let us take a look at the use of the word ‘neighbor’: While it appears only twice in the text of the European Security Strategy (see European Council,

2003), it appears over one hundred times in the ENP strategy paper (see European Commission,

2004), launched to support the Security Strategy. To the east, it is only since the enlargement rounds of 2004 and 2007 that the EU has shared borders directly with countries which are not viewed as prospective members, as the former institutional integration is replaced with an offer of cooperation with neighbors. This means that the EU had to come up with another set of instruments and concepts suitable for a situation in which beyond its borders lay countries that would remain outsiders to the EU. This was a new situation since, until then, integration had been ‘the European response to every major shift in the geopolitical constellation of Europe’ (Tassinari,

2009, p. 4). The strategy of integration, however, works as a means to deal with an outsider only for as long as the countries are not yet members. As Tassinari reminds us: ‘Enlargement really fulfills the European mission when it ceases to be a foreign policy and becomes a “domestic” European matter’ (ibid., emphasis in original). Against this backdrop, we understand the ENP as an effort to order relations with those who will remain outside.

While, in the case of enlargement, the goal is clear (membership), this is more complicated to circumscribe in the case of the ENP (in any event, not membership). Rather, in order to frame its relations with the neighborhood the EU had to start from scratch, including finding out about (reciprocal) expectations on each side. It was therefore no coincidence that, one year before the big-bang enlargement in 2004, the EU introduced the ENP, which channels its external relations with the newly discovered neighborhood; with the accession of Romania and Bulgaria in 2007 and Croatia in 2013, the preliminary enlargement process came to an end. Consequently, relations with adjacent countries then had to be put on a different footing. Founding the ENP, the EU ‘produced’ this neighborhood – or, as Kuus emblematically put it: ‘a place had been crafted out of space by EU institutions’ (Kuus,

2014, p. 16), a space which was turned ‘into a “neighbourhood” as a specific kind of place to be managed through a particular set of policy instruments’ (Kuus,

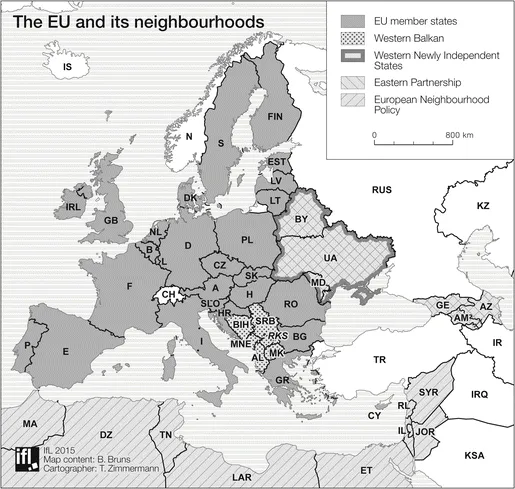

2014, p. 114) (Fig.

1.1).

This process implies the EU’s intention to exert influence to a certain extent on the neighboring countries of the EU. In contrast to countries facing the prospect of membership during the enlargement process, whereby the EU demands full adoption of its acquis communautaire, its leverage with neighbors with no prospects of membership is generally assumed to be much lower (Kelley, 2006, p. 41; Tassinari, 2009, p. 104; Langbein & Börzel, 2013, pp. 572–573; Tassinari, 2009, p. 104). However, the EU still tries to influence these countries in diverse policy fields, including domains of soft power policies such as education, culture and the fostering of non-governmental actors, as well as hard power issues such as migration and security-related issues.

According to Kuus EU neighboring countries were congealed into one distinct object of EU decision-making by the founding of the ENP (see Kuus, 2014, pp. 16–17), thereby turning them into a specific manageable (or even governable) category of outsider.

The case studies in our volume represent two of these country-groups/regional categories. Within the ENP, a regional subgroup—namely, the ‘Western Newly Independent States’ (WNIS), comprising Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova—is the target group of specific and customized EU-driven projects and measures. These countries are supposed to ‘share a similar geo-political background’ (UNHCR, 2005, p. 1). The general assumption on which actors such as the EU or international organizations build their (political) approaches seems to be that the countries in question are confronted with similar problems, for example, when it comes to migration and asylum management (see UNHCR, 2005, p. 1). While this may be the case, the three countries are very different in terms of their standing towards the EU: While Ukraine and Moldova each signed an Association Agreement with the EU in 2014, the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) between Belarus and the EU was never ratified, which means there is no legal basis for relations between Belarus and the EU. By throwing Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova into one pot, the EU creates an unclear spatial homogeniety and at the same time manifests a category of neighbors having to stay outside the Union, since there is no prospect of membership either for WNIS or for other ENP countries.

Another example of the production of assumed homogeneous spatial entities neighboring the EU is the ‘Western Balkan’ region. This term denotes the southeast European countries that represent the next strategic enlargement target of the EU after the admission of Romania and Bulgaria (see Ratiu, 2010, p. 135). It was first introduced during an EU summit in 1998 and is mainly used as a rather technical term by EU institutions and in social research (see Ratiu, 2010, p. 135). However, its use is problematic for several reasons. First, the term ‘Balkan’ has a negative connotation, except for its use in Bulgaria, Albania and Macedonia (see Jordan, 2005, p. 164). Croatia saw itself as located in Central Europe long before its accession to the EU and, at the same time, distanced itself from an identity as a ‘crisis Balkan region’ (Jordan, 2005, p. 164). Second, the term ‘Western Balkan’ comprises countries with very different degrees of integration with the EU. Theoretically, all Western Balkan states do have a prospect of membership and, therefore, belong to that group of countries that might change their status from being outsiders in relation to the EU to insiders, even if this necessitates taking a long-term perspective. In the case of Kosovo, however, we have a situation in which not even all EU member states recognize the country. Its citizens need a Schengen visa in order to enter the EU. At the other end of the scale, we have Croatia, which has belonged to the European Union since 2013.

To sum up, the identities of ‘Western Balkans’ and ‘WNIS’ are constructs which produce a specific spatial order in to simplify the EU’s neighborhood. The case studies gathered in this volume will show that the quite uniform character of these constructs neither corresponds to the often undecided policy of the EU towards these countries, nor reflects the (diverse) expectations and self-perceptions of the countries addressed. With categorizations such as those presented, the EU creates specific geopolitical regionalizations—in other words, it practices a political construction of regions (see Tassinari, 2005, p. 12). This is in line with the critical definition of geopolitics following Ó Tuathail and Agnew, who understand the concept as a ‘discursive practice spatializing international politics to represent it as a world of particular types of places, peoples, dramas’ (Ó Tuathail & Agnew, 1992 in Guzzini, 2012, p. 41): The ‘particular types of places’ thus produced are mainly characterized by their respective relation with the EU. Tassinari has developed a distribution of Europe’s concentric circles, measuring institutional and administrative ‘distance’ on the basis of the degree of integration a country or region has with the EU (see Tassinari, 2005, p. 3). Circle 1 would be the EU core, consisting of the ‘old’ member states; only circle 5 contains candidate countries, and circle 6 contains the EU neighbors with no prospect of membership. ‘They [the countries that are not integrated, circle 6] are cut out by the institutional barrier, although they are increasingly influenced by policies made in Brussels. For current or prospective candidate countries, ‘circle no. 5’, there are reasonable expectations to cross the institutional barrier at some point’ (Tassinari, 2005, p. 4).

Independent of the ‘type of neighbor’ they represent according to the EU’s categories, the third states located close to the EU play a vital role for the EU when it comes to security issues and the maintenance of inner stability and prosperity.

Extra-territorial Engagement as a Common Denominator

For each of these ‘types of neighbor’, the EU has in mind a certain political offer, a vision of how these regions should be so that they conform to the EU’s own interests. Against this background, we decided to use the term ‘extra-territorial engagement’ in order to grasp the EU’s approaches to its diverse neighborhood.

The term ‘extra-territorialization’ was originally used to describe the relocation or outsourcing of migration control to neighbor states of the EU (Rijpma & Cremona, 2007, p. 11; Zeilinger, 2012, p. 63), meaning that third countries are involved in EU policies through certain agreements (Cardwell, 2009, p. 160). However, the notion of extra-territorialization can be broadened to include measures of different policy fields aiming at influencing the domestic policies of a third state for internal EU security reasons (see Wichmann, 2007; see also Bruns & Happ, Chap. 7, Laube & Müller, Chap. 3, and Makarychev & Yatsyk, Chap. 5, all in this volume). From our point of view, it does not make sense to restrict the notion to one domain (that of migration); on the contrary, it can be applied fruitfully to other policy fields. The reason for this is that extra-territoriality captures especially well the two-sidedness of EU activities beyond its borders.

Etymologically, the term is composed of two parts: ‘Extra’, which means simply ‘outside’; and ‘territory’, which stems from a Latin loan word defining a political entity, a dominion—for example, a city or a sovereign state. While, from a scientific point of view, these territorial entities can be seen as socially constructed, they do have a political and strategic meaning in practice. Thus, turning to the term ‘territorialization’, we understand it, first, as an active process of producing and shaping a territory. The concept of ‘territoriality’ helps to reveal what this process of construction looks like. It can be seen as the prevalent principle of political power, as well as the outcome of specific socio-technical practices (see Painter, 2010). According to Sack, it can be defined as ‘an attempt to affect, influence, or control actions and interactions (of people, things, and relationships) by asserting and attempting to enforce control over a geographic area’ (Sack, 1983, p. 55 in Rios & Adiv, 2010, p. 7, own emphasis). In this sense, we understand the EU’s extra-territorial engagement as a spatial-strategic means to control socio-spatial relations on multiple scales in sovereign states outside the EU. We are aware that there exist other concepts covering the EU’s relations with its neighbors; for example, ‘external governance’, stemming from political sciences and being defined by...