![]()

ONE

THE ‘EVENING STAR’

Bright Star! Would I were steadfast as thou art –

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors –

No – yet still steadfast, still unchangeable.

JOHN KEATS1

Among all the objects in the heavens, Venus is unmistakable, as it is far more brilliant than any other planet or star. It has attracted the attention of sky-watchers from prehistoric times, and the wonder it inspired is attested to in some of the oldest written documents we possess. Those who wrote them still communicate to us across a distance of some 5,000 years.

The motions of five planets, or ‘wanderers’ – Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn – were no doubt recognized before the dawn of recorded history. They fell into two groups: Mars, Jupiter and Saturn could travel all around the heavens, while Mercury and Venus were more confined, and remained within certain bounds of the Sun, either leading it into the morning sky or lagging behind in the evening sky.

We now know that the ‘wanderers’ are other worlds, in orbit (like Earth) round the Sun. Mercury and Venus lie closest to the Sun, and are known as ‘inferior’ planets; Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, as well as Uranus and Neptune, discovered only in the telescopic era (of course, in addition, there are other objects that are also planets – for instance, the dwarf planets Ceres and Pluto), lie further from the Sun, and are known as ‘superior’ planets. Venus is the planet which approaches closest to Earth. Moreover, being surrounded by a dense and highly reflective atmosphere of clouds, Venus outshines all the other objects in the night sky other than the Moon and the occasional supernova or a comet (of which the last observed in our galaxy was in 1604).

Not surprisingly, because of its brightness and the complicated pattern of its motions in the sky, Venus has been an object of intense interest from earliest times. It is named in the inscriptions of the first agricultural civilizations. These appeared in the Nile valley in Egypt, which runs from the cataract of Upper Egypt to the delta of Lower Egypt, where the annual flooding of the Nile produces fertile fields, and in the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates in Mesopotamia (the Greek word for ‘land between the rivers’).

Because the flooding of the Nile predictably follows a cycle, it was recognized by astronomical events. The flooding occurs in August at the time that Sirius rises just ahead of the Sun into the pre-dawn sky. This became the most important astronomical observation among the ancient Egyptians – their very livelihood seemed to depend upon it – and became the basis of their reckoning of the seasons. (Thus akhet was the season of inundation, peret that in which the land emerged from the flood and shomu that of the drought.) This led the Egyptians to adopt the first solar calendar in history, consisting of twelve months of thirty days each, and five additional days at the end of the year. The great historian of ancient astronomy Otto Neugebauer referred to this as ‘the only intelligent calendar which ever existed in human history’.2

Though their calendar was intelligent and elegantly straightforward, the Egyptians had an extremely complicated religion, involving the worship of many gods. At an early stage, they worshipped the Sun as one of the chief gods, Ra.3 The great river of heaven, the Ur-nes, marked the ecliptic, the Sun’s path through the heavens, and along the river floated a boat whose passenger was a disc of fire, the Sun itself. The same stream carried the bark of the Moon (Iââhu; sometimes called the left eye of Horus), which appeared out of the ‘door of the east’ in the evening. The stream also carried the planets. Ûapshetatui (Jupiter), Kahiri (Saturn) and Sobkû (Mercury) steered their barks in a forward direction, like Ra and Iââhu, but Doshiri (Mars) sometimes oared backwards – which shows that the Egyptians must have been especially impressed by the length of the retrograde or backward loop the planet exhibits around the time it appears opposite the Sun in the sky. (Jupiter and Saturn also show such loops, but less prominently.)

In the Egyptian scheme, Venus received special treatment. It was regarded as a close confederate of the Sun, and had two names. It was Uati, the first star of the night, when it followed the Sun as an Evening Star, and Tiû-nûtiri, the harbinger of the Sun, when it preceded it as a Morning Star. It was also sometimes called Benin, the heron. This bird, still common along the banks of the Nile, dives under the river, then rises again, in the same way Venus, the celestial heron, disappears into the Underworld for long periods of time, but always returns.

The most assiduous Venus observers of antiquity – and, indeed, the most diligent at least until the Aztecs of Mesoamerica of circa 1000 CE – were the Sumer–Akkadians, the people of the other great agricultural civilization that developed in Mespotamia (a term properly referring to the ‘Fertile Crescent’ between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, north and northwest of Iraq in modern days, but by extension used to describe the region from the Zagros Mountains in the northeast to the Arabian Desert in the southwest).

Compared to the Egyptians, the Sumerians are little known. The Greek historian Herodotus, though he had much to say about Egypt, had never heard of Sumer, since it no longer existed in his lifetime. It was not until the middle of the nineteenth century – when then-assistant to the British ambassador in Constantinople Austen Henry Layard, with the assistance of Hormuzd Rassam, began excavating the site of Nineveh (near the modern city of Mosul, so badly damaged during the Iraq War of the early 2000s) that the recovery of its history and proud legacies began. Even so, it receives dismissive treatment in most histories. The Sumerians created, by means of a system of irrigation canals, the first urban society, introduced mass production techniques and evolved a system of writing based on cuneiform (a system of marks made in clay tablets with the slanted edge of a reed stylus) which at first was used mainly by merchants as a means to keep track of the flow of goods. As the Sumerian city-states became more powerful, the script was used to keep a large bureaucracy humming and to keep royal records in order. In time, the scribes began to keep track of not only the traffic of goods but the traffic in the heavens. Eventually they would note astronomical phenomena in records maintained for over a thousand years. These provided the basic data that nurtured the beginnings of astronomy.

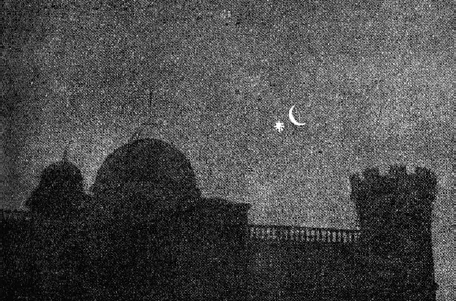

Since the Sumerians, unlike the Egyptians, used a lunar calendar, they were keenly interested in determining when the thin crescent Moon could first be seen in the sky after sunset, an observation taken to mark the beginning of each new lunar month. To get a better view of the horizon, the sky-watchers began to observe from the elevated platforms of seven-level terraced ziggurats. The ziggurat of the ancient Sumerian city of Ur (‘Ur of the Chaldees’ in the Bible, the reputed birthplace of Abraham), built in the period 2112–2095 BCE, is the most famous. Among other tasks, the priest-astronomers were responsible for deciding when to add an extra, thirteenth, month to their lunar calendar in order to keep it synchronized with the seasons and religious festivals.

The crescent Moon (with ‘Earthshine’ illuminating the dark side), Mercury and Venus (just over the hill, above its reflection in the pond).

Venus and the Moon, 2 July 1921, as seen above Camille Flammarion’s observatory at Juvisy, near Paris.

Because of its brilliance in the night sky – sometimes it was even known as the ‘torch of heaven’ – Venus attracted the attention of the priest-astronomers, especially as it frequently lines up close to the crescent Moon. Indeed, the sight of these two celestial bodies together is among the most impressive phenomena of naked-eye astronomy. Moreover, the Sumerian Venus, known as Inanna, was the most important deity in the Sumerian pantheon. Because of this, her wanderings through the heavens not only were of great interest to the priest-astronomers, but inspired religious cults and gave rise to a vast body of myth.

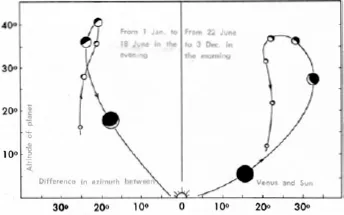

As seen from Earth, Venus passes alternately on the near and the far sides of the Sun, and is then said to be at inferior and superior conjunction, respectively. On Venus first becoming visible to the naked eye in the evening sky (after superior conjunction), the Sun lies some 6° below the horizon. Then, from evening to evening, Venus makes a slow ascent, separating further and further from the Sun while increasing in brightness and prominence. At last, about two months after its first entrance on the stage of the evening sky, it reaches a maximum separation (greatest elongation east) of 46–47°, setting some four hours after the Sun. Now, it begins to drop sunward again, at first gradually and then at an ever-increasing pace. Some 144 days after it first appeared in the evening sky it is lost in the solar rays (at inferior conjunction), and is invisible for a time, typically a couple of weeks, before rapidly re-emerging into the morning sky as a Morning Star, west of the Sun. (The precise duration of its invisibility depends on a number of factors, including sky conditions, the observer’s geographical latitude, his or her visual acuity, training, the difference between the azimuths of Venus and the setting or rising Sun, and so on.4) Now it holds forth as a Morning Star for 440 days before disappearing behind the Sun (at superior conjunction), after which the whole process repeats.

We know from a Sumerian text written sometime between 2150 and 1400 BCE called ‘The Descent of Inanna’ that she was originally a rain deity and fertility goddess. She was also bride of the god Dumuzi-Amaushumgalana, who represented the growth and fecundity of the date palm (hence she was sometimes known as the Lady of the Date Clusters). Setting her heart on ruling the Underworld and attempting to depose her sister (Ereshkigal, Lady of the Greater Earth), she failed in the attempt, was killed, and then dispatched to the Underworld. Eventually, Enki, the Lord of Sweet Waters in the Earth, managed to bring her back, but only on condition that she offer a substitute in her place. She chose her husband Dumuzi, when she found him feasting instead of mourning her absence. In the end, Dumuzi and his sister Geshtinanna were allowed to alternate as her substitute; each spent half a year in the Underworld, half a year above it. The myth of Inanna and her descent into the Underworld clearly reflects the planet’s observed path in the sky.

As early as 3200 BCE Inanna was being worshipped in the Eanna temple in the city of Uruk, located about 250 km south of Baghdad on an ancient branch of the Euphrates called Warka (the biblical Erech). The city was settled by about 4000 BCE and by 3200 BCE covered an area of at least 250 hectares (about 2.5 square km) and had 25,000–50,000 inhabitants.5 Later, as one Sumerian city-state achieved dominance over another (thus Uruk was followed by Kish, then Nippur, Isin, Lagash, Eridu and Ur), her influence spread, and she acquired the characteristic domains of the deities of the conquered city-states until she had achieved the status of being the most prominent female deity in ancient Mesopotamia. This may account for the fact that, ‘unlike other gods, whose roles were static and domains limited, Inanna had a reputation for being young and impetuous, constantly striving for more power than she had been allotted’, and notorious for her ill-treatment of her lovers.6 In any case, in this way she acquired a dual nature as the goddess of both warfare and sexuality.

Venus’s positions relative to the Sun in 1964. At left, from 1 January to 18 June, it appears as an Evening Star, then from 22 June to 3 December as a Morning Star.

Her cult grew greatly after the conquest of the Su...