![]()

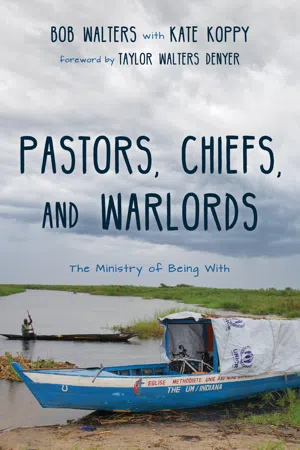

On the River

The Third Tour

![]()

Going the Other Way

or, An Introduction to the Third Tour on the Congo River, January 2012

The Friendly Planet Team’s third tour in 2012 turns our route around in the other direction. We will be riding from Tenke up to Lubudi and then on to Kamina, where the bishop wants me to come to see him. I’m happy to do this because I want to retrace my 1998 ride through the Lubudi District, and I especially want to see Kansenia.

The team includes many of the same people, with some notable changes. Joseph Mulongo was elected the chief of the delegation to the 2012 General Conference of The United Methodist Church, held in Tampa. He is busier than can be, traveling to Lusaka, then to Liberia. So, Mumba will be taking his place as team leader. Two distinct teams have formed: the boat team wears the original teal blue FPM shirts; the bicycle team wears the bright yellow shirts of the Fondo d’Congo. We have no trouble recruiting team members.

With Mumba as team leader, the bicycle team will ride up to Kamina to see the bishop. Mumba has selected this team from the Tenke District and appointed a young pastor named Junior as his number two. Meanwhile, with Éléphant as captain and a local crew, Mary is going to run the boat team. The bicycle team will ride up to Kamina to see the bishop; the boat team will come down the Congo River to Bukama and pick the cyclists up there. Together, we’ll take the Indiana to Mulongo.

We have new bicycles this year. We’ve purchased five mountain bikes from Zambikes in Lusaka. They are Trek bicycles, made in the Giant Bicycle factory in China, purposed for Africa and branded Zambike. We’re going to give them a try. There’s a risk here as we have no ready supply of spares.

After breakfast and team photos, we’re off. I have no idea what day it is, and it’s not my job to keep track.

Mumba leads the bicycle team north on a quite rideable dirt road. After 28 kilometers, we reach Tshilongo, a high point on the road that boasts three cell towers. It is also on the railroad track, so it has electricity. We stop just long enough to send quick greetings, and we’re off again.

This countryside is spooky familiar. I can’t pick out a particular landmark and say for sure, but I know I’ve been here before. Of course, I have. Back in 1998, I rode this route from Tenke up to Kansenia Gar. Here’s a dilapidated train depot where we stopped for a meal, I think. Maybe it was a dream. Most of my time in the Congo in 1998 now feels like a dream. I was out here with men I didn’t really know, in an inhospitable land, with no safe water to drink. (This was before bottled water.) There were rumors of a war breaking out just north of us. That didn’t bother me, really. It was more that I was just lost: with no one to talk with, I was alone in my head. I can’t say that I was afraid, just sort of lost, disoriented.

That ride was somewhere buried deep in my brain. I’ve lost so many memories from those years, but that ride is so central to who I have become that I recognize minor landmarks along the road—railroad crossings, bends in the road, even groves of trees. There’s the depot where we stopped to find a place for the night, still the same ruined brick building, floor blackened by decades of charcoal fires.

That night, back in 1998, I was taken to an old Belgian farmhouse. I had no idea where we were going and no idea what we would find. It was the first night out on a journey of unknown length, a journey that was entirely outside my control. I was totally dependent upon my Congolese colleagues. We had met the day before, and we did not share a common language. This first night I will never forget.

The room I was taken to was large, high ceilinged, but clearly not lived in for years. There was an old mattress in one corner, and it reminded me of the sleeping spaces homeless people in the US set up for themselves wherever they can. My colleagues gave me a candle and a box of matches and left me on my own.

I was letting go of the need for control. All worries were melting away. No mosquito net, but no worry. Dark and alone, no worry. I had foolishly launched into an adventure with no plan, no worry. The room had the aura of a nightmare, but I was not dreaming yet. Somewhere between not dreaming and dreaming, I fell asleep and did not wake up until the sun came up. I woke up more on account of the heat than the light.

There was hot water for tea and some day-old bread for breakfast the next morning. We got an early start on the road to Kansenia, 50 or so kilometers away.

![]()

Kansenia Gar, Remembered

Kansenia Gar in 1998 is when the world changed for me.

It was the first of my bicycle adventures, and I was riding my Cannondale F500 mountain bike. We hit Kansenia Gar on the third day.

Kansenia has three distinct forms. Kansenia Gar is the railroad station on the tracks that run along the ridge. In the valley, there’s Kansenia Mission, the old Catholic mission station and girls’ school, and Kansenia Village, where the people live.

The seven-kilometer ride from Kansenia Gar to Kansenia Mission took us along the ridge and down into the valley. It is the most beautiful valley I’ve ever seen. It stretches to the horizon and is encased in a horseshoe-shaped mountain ring. It is a shade of green I had never seen before like a new color was just invented for this valley. I felt like we were standing over Shangra-La, or like we had been transported to some vegetation-rich planet previously undiscovered.

We had to follow the steep, zig-zagging, washed-out gravel road to get down into the valley. As soon as we began the descent, a small group of young men arrived to help us down. Happy for the help, I handed my loaded mountain bike over to one of them. Not wanting the visual of a white missionary followed by a line of porters, I walked along behind.

On the way down, we walked through a small river of waterfalls.

At the bottom, we walked past the mission. Its classic colonial architecture was out of place in the jungle. In the colonial period, many important Congolese families sent their daughters to this prestigious boarding school for a quality education. Even then, this was unusual and represented the antithesis of the Belgian attitude toward educating the Congolese, which is to say, not educating them. In 1998 it seemed strange that people here remembered a time when girls, at least those from the elite families, went to good schools. It doesn’t appear that the school is still functioning as a boarding school, and if it is still open, it’s barely alive.

I thought that if I needed a place to spend the night, we might stay at the mission, but we passed on by. At this point, people from the village had joined our walk, and we were headed for the United Methodist church.

The United Methodist Church in Kansenia Village was not much of a building. Certainly, compared to the mission, it was a hut. That’s just the point. The Catholic mission was colonial in its construction. The United Methodist church had been built by its congregants with their own resources. It had low walls of locally baked bricks with a sagging grass roof hanging over the walls all the way to the ground. We were invited inside and ducked through the door into the dark sanctuary. The floor was dirt. The roof was supported by unmilled tree trunks three down the center aisle. The room was packed with excited worshippers. I was taken to the front and given a bamboo tripod chair so that we could have church.

Worship services in these village churches have been some of my favorite times. The theology is Christian, and the acts of worship are locally rooted. The Congolese Methodists have brought their traditional drums, singing, and dancing into the church. It is raw, and it is beautiful.

After worship, a woman brought her sick child and two chickens to us in the pastor’s hut. I was asked to pray for the child. Sure, Christian pastors all over the world enter homes and pray for the sick. But this was way more like the role of the traditional healer. There was an expectation of appeasing God with the offering of the chickens.

It was at Kansenia Gar in 1998 that I began to listen. This was the deep listening that eventually became my Doctor of Ministry thesis, Scripture as a Tool of Community Development. There’s a copy of it in the library at Christian Theological Seminary in Indianapolis, and I have the only other copy. I was so unhappy with the writing, that I only ordered one souvenir copy for myself to disappear on my bookshelf, and I didn’t file it on the seminary’s electronic search engine for others to find it. Perhaps someday, I’ll rewrite it into a readable book and publish it.

After we had climbed back out of the valley, we were offered beds for the night in the home of the train station manager, a United Methodist lay leader. As was the pattern, I got the good bed—old, sagging springs, worn cover, small dark room, but comfortable and clean.

Our host suggested that he could get us on the train to Lubudi, our next destination. That would save us a whole day of riding. He did not tell us the train was a freight train, and I didn’t think to ask. I was learning to leave the planning to my Congolese colleagues.

In the morning, we went to the station to wait. As the district superintendent and I sat on the stoop, we watched a local farmer lead a team of traction cows pulling a cart into the station yard. The cart was carrying bags of maize that would be loaded onto the train bound for Lubudi. We, the United Methodists in the Lubudi district, had nothing like this team of cows. The church’s cornfields were sources of needed income and food for district conference gatherings. While we were touring the churches, we inspected the cornfields and saw that our farmers were tilling these fields by hand.

I asked the district superintendent how much a team like that would cost, and he figured that with cart and plow, the team would cost under $2,000. This was where I first began to question the mission model we were using. The United Methodist Church, through the General Board of Global Ministries, had two agricultural mission stations in Katanga. One was run by a salt of the earth evangelical couple from Ohio who, out of compassion for the Congolese people, had moved a whole farm from Ohio to Zaire in shipping cont...