![]()

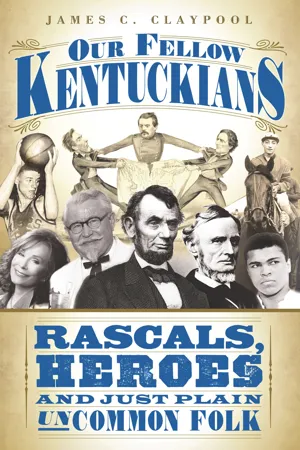

Jefferson Davis

1808–1889

“I don’t want to be the president of the Confederate States of America; I just want to command the army.”

Jefferson Davis—president of the Confederate States of America—from Davisburg, Kentucky

A rallying cry among Union soldiers during the Civil War proclaimed, “We will hang Jeff Davis from a sour apple tree.” Given their horrendous casualties and sufferings on the battlefield, such bitterness toward the leader of the Confederate government by Union soldiers is understandable. Yet, ironically, Jefferson Davis, the object of such intense hatred, had once been one of America’s most famous military heroes as well as one of the nation’s foremost statesmen.

Jefferson Finis Davis was born in 1808 on a farm in rural western Kentucky. His father, Samuel Davis, named the family’s tenth and last child Jefferson for the contemporary president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, whom Samuel greatly admired. Men in the Davis family, including Samuel Davis, had traditionally served their nation as army officers, some in the Revolutionary War and others in the War of 1812. By 1812, Samuel had relocated his family to Wilkinson County, Mississippi, where their precocious five-year-old son, Jefferson, attended a log cabin school. After two years, Samuel Davis was dissatisfied with his son’s rudimentary education and sent him to study at a school run by Catholic priests in Washington, Kentucky, even though Jefferson was at the time the only Protestant enrolled.

Davis stayed two years in Kentucky, returned home and studied at a prep school in Mississippi. In 1821, at age thirteen, he was judged ready for higher education and entered Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky. He spent three years at Transylvania, where he was a popular student, often gaining acclaim both for his singing and speaking abilities. Davis’s father, whose success as a Mississippi planter had placed him in contact with influential state and national politicians, used these political connections to secure his son an appointment in 1824 to West Point. Thus, in keeping with the tradition of males from his family serving as officers in the army, Jefferson Davis reluctantly left Transylvania, not having completed his senior year, and entered the military academy.

Jefferson Davis. Courtesy of the author.

Davis, who ranked in the lower half of his class at West Point both academically and for discipline marks, was commissioned a second lieutenant upon his graduation in June 1829 and assigned to an infantry regiment in Wisconsin. His life in the army took its most interesting turn in 1832 when, while he was serving as an aide to another Kentuckian, future U.S. president Colonel Zachary Taylor, Davis met and fell in love with Taylor’s daughter, Sarah Knox Taylor. Since Taylor did not approve of the match, Davis resigned his commission, and on June 17, 1835, he and Sarah were married.

Tragedy soon struck the newlyweds. While they were visiting Davis’s oldest sister at her plantation deep in the marshlands of Louisiana, both Sarah and Jefferson contracted malaria. Sarah died on September 15, 1835, just three months after the wedding, and in 1836, after his own difficult recovery, Jefferson Davis, inconsolable over the loss of his wife, moved to a plantation in Mississippi owned by his brother Joseph. Jefferson Davis spent the next eight years as a recluse, reading history, studying government and politics and engaging in private conversations about politics with his brother at the plantation in Mississippi.

In 1843, Jefferson Davis, by now somewhat healed and acting on his interest in politics, ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat but lost to his Whig opponent. A year later, Davis ran again and was elected to serve in Mississippi’s At-large District as a member of the House of Representatives. He entered the House on March 4, 1845, and in December married Varina Howell, the seventeen-year-old granddaughter of the late and greatly admired eight-term governor of New Jersey, Richard Howell.

In June 1846, just one month after fighting had begun between the United States and Mexico in the Mexican-American War, Davis resigned his House seat, returned home and raised a volunteer regiment, which he commanded as the regimental colonel. He insisted that his troops were to be armed with the new Whitney percussion rifles; because this was the first regiment to use them, the troops he commanded became known as the “Mississippi Rifles.”

In a rather strange twist, Colonel Davis and his regiment were placed under the command of Davis’s former father-in-law, Zachary Taylor, now a general. Any tensions that may have existed between Davis and Taylor were quickly set aside once the fighting began. In September 1846, the Mississippi Rifles participated in the siege of Monterrey, Mexico, where they used their new percussion rifles with particular effect against the enemy’s infantry. Davis was seen on his horse commanding throughout the battle, urging his troops onward.

In February 1847, at the Battle of Buena Vista Ranch, Davis also played a major role in the American victory. Wounded in the foot early in the battle, with blood filling his boot, Davis stayed mounted in command until his regiment helped carry the day, after which he fainted and was carried to safety. It was later said that Davis had played a command role at the Battle of Buena Vista second only to the one played by Zachary Taylor, the battle’s commanding general. This point was confirmed when Taylor visited Davis’s bedside later to recognize his bravery and initiative at Buena Vista and reportedly exclaimed to his former son-in-law, “My daughter, sir, was a better judge of men than I was!”

A national war hero, Davis returned to Mississippi and was appointed in December 1847 by the state’s governor to fill a U.S. Senate seat left vacant by a death; he was elected to serve the rest of the term in January 1848. Jefferson Davis chaired the Senate Committee on Military Affairs from 1849 until 1851, after which he resigned his Senate seat to run for governor of Mississippi, a race he lost by only 999 votes. Out of office but still politically involved, Davis campaigned in several southern states on behalf of Franklin Pierce, the Democratic candidate for president in 1852. After his election, President Pierce made Davis the secretary of war. Davis’s most important work in this post involved a report he submitted to Congress detailing various routes for the proposed Transcontinental Railroad.

Davis resigned his cabinet post to run for the Senate in Mississippi after the Democrats selected James Buchanan as their presidential candidate in 1856 rather than Pierce. Davis won the election and reentered the Senate on March 4, 1857. The next four years of Jefferson Davis’s life would be history making as first he struggled to preserve the Union and then headed the government that opposed it. During the first year of his term in the Senate, Davis was quite sick, suffering from an illness that nearly cost him his left eye. On July 4, 1858, Jefferson Davis, one of the nation’s most influential Southern senators, while sailing on a boat in waters just outside of Boston, delivered a powerful anti-secessionist speech that captured headlines nationally. Three months later, in another speech at Boston, he eloquently reiterated his position by urging all parties concerned to join together to help preserve the Union.

Davis, like his Southern colleagues in Congress, believed that states had the rights to secede from the Union, but he believed doing so would be both a serious mistake and a national tragedy. Lincoln’s election as president in November 1860 placed the nation at the brink of war. Davis was now conflicted by the realities of Lincoln’s election and his understanding of what results might lay ahead. As secretary of war under Pierce, Davis had become convinced that the Southern states did not have the military and naval resources to defend themselves. But war was looming eminent in the spring of 1861 and Jefferson Davis was once again to become a reluctant victim of his Southern heritage.

South Carolina’s departure from the Union in December 1860 set the stage for ten other Southern states, including Davis’s home state of Mississippi, to secede. Davis’s last speech before his departure from the Senate was a summation of a life now entangled by forces seemingly beyond any one individual’s control. As he rose to bid his farewell, Davis delivered what was perhaps his finest speech. They were words spoken from the heart, a speech that spoke of his love for his country, of his military service and of the personal sadness he felt because of the Union’s fragmenting. When he concluded, there were many wet eyes on the Senate floor as well as audible weeping in the galleries. Even the Senate’s grim-faced Republicans seemed to understand that this was a man who loved his nation more than they had ever suspected.

Davis’s four years as president of the Confederacy (1861–65) were controversial. Perhaps he would have been better posted as a general in command of an army. Who can say? His supporters in the South revered him as a tragic statesman swept away by forces beyond his control. His detractors, both in the North and the South, slandered and maligned him as being weak and ineffective. He survived the war, was captured, charged with treason, imprisoned for two years and then was set free in 1869. In his later years, Davis traveled abroad extensively and in 1881 completed a two-volume book entitled The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government.

In October 1889, Davis’s Short History of the Confederate States of America was released. Both of his books remain standard source materials concerning the history of the American Civil War. He died in New Orleans on December 6, 1889, of unknown causes, at age eighty-one. His body was taken from New Orleans for burial in Richmond, Virginia, by continuous day and night cortège, producing a funeral said to have been one of the largest ever seen in the South. The South is dotted with memorials to Jefferson Davis, but perhaps the most impressive stands near Davis’s birthplace just outside of Fairview, Kentucky, a two-hundred-foot obelisk paid for entirely by private donors.

![]()

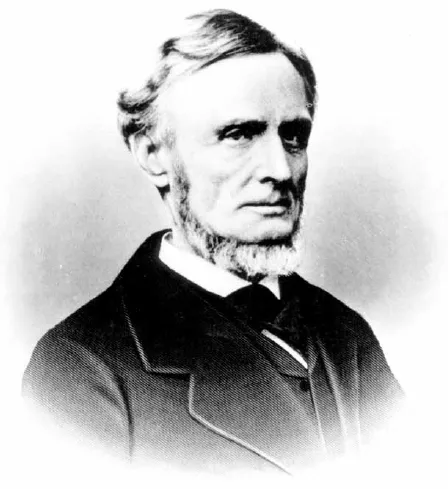

Abraham Lincoln

1809–1865

“I certainly would like to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky.”

Abraham Lincoln—president of the United States of America (1860–65)—from Hodgenville, Kentucky

Abraham Lincoln declared at the beginning of the Civil War in 1861 that to stem the tide of secession in the South and to preserve the Union, he must have the state of Kentucky. His meaning was clear, and for the next two years Lincoln and Unionists in the state did everything, legal or otherwise, to ensure that Kentucky, a strategic military gateway to both the North and the South, remained a part of the Union. Abraham Lincoln, the son of Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln, was born in modern-day Larue County, Kentucky, on the north fork of the Nolan River in 1809. His father was a farmer, and like so many of the families living on the frontier of America the Lincolns would move from time to time seeking better farmlands. Thomas Lincoln was opposed to slavery and decided to move his family across the Ohio River to get away from it. In 1816, when Abraham was seven, his family moved to a site along the Little Pigeon Creek in southern Indiana, and then a few years later the Lincolns moved to Illinois.

Abraham Lincoln’s ties to Kentucky, however, remained deep. His wife, Mary Todd Lincoln; his law partners in Illinois; his closest friend, Joshua Speed; and his political mentor, Henry Clay, were all from Kentucky. On occasion, Lincoln returned to Kentucky to visit his in-laws in Lexington or to spend time with the Speeds, who resided at a large estate, Farmington, located just outside of Louisville. It’s little wonder that Lincoln understood Kentucky’s strategic importance as well as that of the Ohio River, which flowed for over six hundred miles along Kentucky’s border.

Lincoln, a Henry Clay Whig turned Republican, was elected president of the United States in 1860. He became the man who helped split the Union and the one who helped preserve it. Lincoln’s election was the red flag that drove the South to secession and violence. Confident that their cause was just and their fighting men were superior to those of the North, the military forces of the newly constituted Confederates States of America fired upon the Federal installations at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861, thus starting the American Civil War. Lincoln immediately issued a Federal call to arms to state militias calling for seventy-five thousand men. Kentucky’s militia was part of the quota Lincoln had set, but Kentucky’s governor, Beriah Magoffin, refused to honor Lincoln’s call for troops, declaring that he would “send not a man nor a dollar for the wicked purpose of subduing my southern sister states.”

Abraham Lincoln. Courtesy of the author.

The seeds of rebellion in Kentucky had been planted by Governor Magoffin, and Lincoln and the Unionists in Kentucky moved rapidly to see that they were not allowed to grow and spread. In the special congressional elections held in Kentucky in June 1861 Unionists won nine of ten seats, the lone exception being a district in far western Kentucky. Two months later, the Unionists captured a two-thirds majority in the Kentucky General Assembly and elected strong supporters of the Union to leadership positions in both the House and Senate. Meanwhile, Magoffin had declared Kentucky a neutral state, but neither the Confederacy nor the Union paid this any heed.

Confederate military forces moved into Kentucky in the fall of 1861, violating the state’s neutrality, and Lincoln armed the state’s pro-Union Home Guards with several thousand rifles dubbed “Lincoln guns.” The Union also established a recruiting camp in central Kentucky at Camp Dick Robinson near the Dix River. There would be several hundred minor military actions in Kentucky during the Civil War but only one major battle, the Battle of Perryville in October 1862. That battle was in response to a Confederate invasion of Kentucky that threatened to place the state into Confederate hands. However, the invasion was blunted and turned back at Perryville. Other than raids by Kentuckian John Hunt Morgan and other Confederate mounted raiders, nothing of military significance took place in Kentucky for the remainder of the war. During one of Morgan’s raids into Kentucky a concerned Lincoln telegraphed his commanders that a stampede was taking place in Kentucky and asked them to please look into this matter at once.

The Union’s military triumphs in Kentucky were paralleled by Unionist political victories. In August 1862, Governor Magoffin resigned and was replaced by a pro-Union governor, and the powerful Unionist head of the State Senate was reelected to his post. Nonetheless, at times, with about one-third of Kentucky’s population pro-Southern, the rights of Kentucky citizens were violated either by the use of martial law or by the illegal confiscation of their properties.

Though a native son, Lincoln was never popular politically in Kentucky. When Lincoln ran for president in 1860, he finished fourth in a four-man field, receiving only 1,364 votes statewide. Even some members of Lincoln’s own wife’s family in Lexington, the Todds, were hostile toward Lincoln; some of them, in fact, would die while fighting with the Confederate army. On one occasion, Lincoln, shunned by his aristocratic in-laws, reportedly proclaimed, “The Todds need two d’s in their name, and God Almighty only needs one!”

Another defining moment with regard to Lincoln’s association with Kentucky came when he issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, freeing the slaves in all the seceded states. Kentucky, though divided in its loyalties, had remained in the Union. Still, up to three-quarters of the slaves in the Commonwealth of Kentucky were already freed or had fled to freedom by 1863, and the remainder would be freed in 1865 by the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. The issue that followed was that if slaves were defined as property, as they had been before the war, then the property rights of Kentucky slaveholders had been overridden by political actions and no compensation had been offered them. The bitterness that this created played out in two ways as later Kentuckians filed lawsuits asking for financial restitution but never received any, and immediately following the war, Kentuckians generally supported Democrats, many of whom had fought for the South. A clear view of the political future in Kentucky came during the presidential election of 1864, in which Lincoln, at the highpoint of his presidency, lost Kentucky, winning only 28 percent of the votes cast.

Lincoln’s assassination in 1865 left it unclear how Kentucky might have fared in a Lincoln-led postwar era. Many Kentuckians soon came to view the Civil War as a tragedy that had divided both the nation and their state. Many citizens living in central Kentucky and parts of western Kentucky romanticized the war, believing that the Confederacy had fought for a noble cause but lost. Most of the citizens living in the northern and eastern parts of Kentucky either had stood firmly with the Union or had stayed benevolently neutral.

The real question that needs to be asked is what would Lincoln’s legacy be to Kentucky? In general, Lincoln’s stature grew as time passed. Kentuckians came to honor their native son’s difficult role as protector of the Union and mourned his tragic end. On February 9, 1909, one hundred years after Lincoln’s birth, a commemorative ceremony was held at Hodgenville, Kentucky, near Lincoln’s birthplace. Kentucky’s Republican governor, Augustus E. Willson, made it clear to the crowd assembled that Lincoln should be remembered and honored foremost as being a Kentuckian. First recognizing that Lincoln was claimed by the entire nation, Willson observed that some states had special claims to Lincoln when he said,

Illinois says He was mine, the man of Illinois, here on my prairies he ripened into noble manhood and here he made his home. Indiana says He was mine. In my southern hills the little child grew strong and tall. While each is true, Kentucky surpassed both because it could say, I am his mother, I nursed him at my breast, my baby born of me. He is mine. Shall any claim come before the Mother?

![]()

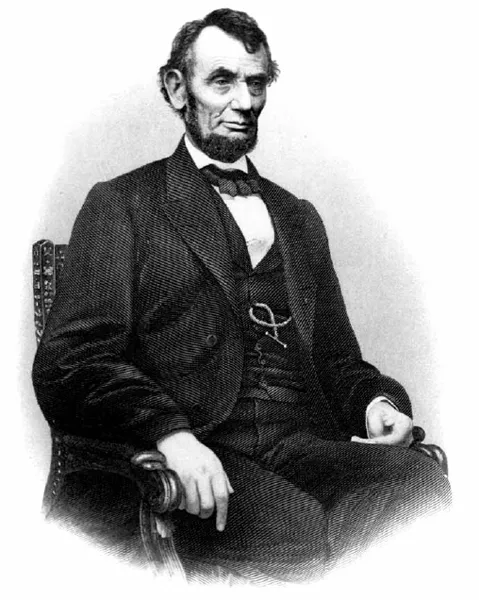

Cassius Marcellus Clay

1810–1903

“Look here, sheriff, her brother said it would be all right.”

Cassius M. Clay—ex-slaveholder who became a spokesman for the emancipation of slaves—from Madison County, Kentucky

Cassius Marcellus Clay (the name shared by...