![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE BRAHMINS OF BOSTON

Boston Brahmins are the first families of Boston, they who are descendants of the English Protestants who founded it. The term was coined by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., who adopted it from the Sanskrit. A Brahmin is a member of the highest caste among the Hindus. Holmes’s Brahmins were not strictly religious but were equally powerful.

The Brahmins were influential in the arts, culture, science, politics, trade, and education. The nature of the Brahmins is summarized in the doggerel “Boston Toast” by Harvard alumnus John Collins Bossidy:

And this is good old Boston,

The home of the bean and the cod,

Where the Lowells talk only to Cabots,

And the Cabots talk only to God.

In Boston history, John Winthrop and many other Puritans arrived in America on the Arabella and sister ships and came to Boston in 1630. No Cabots or Lowells were aboard. They came later and, like all Brahmins, are often associated with Beacon Hill, but that also came later, as we’ll see in the next chapter. The wealth of these families arose from shipping, but that would change as the city would change.

When the British evacuated Boston and, subsequently, when the Revolutionary War ended, the composition of Boston’s population changed, especially at the top. Many of the pre-Revolution merchants were wealthy Tories, and they had left town with the British troops, many of them headed for Nova Scotia, some to England itself. Their departure also left holes in the mercantile fabric. These people not only had wealth but also had held leadership positions in the town. Those holes would necessarily be filled by other Bostonians, who would in turn become the elite of the moneyed class.

An iconic symbol of the change in leadership was the new State House that was designed by Charles Bulfinch and built on the crest of Beacon Hill in 1798. The area around the State House and on the southern part of Beacon Hill would soon be developed to provide new houses for these merchants. They made their fortunes in shipping but would turn to other things before too long.

After the Revolution, Boston’s seafaring ways resumed and would continue into the nineteenth century. Their trade was mostly with the West Indies, especially with the British possessions in the Caribbean Islands that supplied sugar, cocoa, tobacco and molasses. Boston’s merchants traded cod, whale oil, lumber and molasses. Resumption of the trade that had slowed during the Revolution brought new money to the coffers of the merchants, money that could be invested in old and new businesses as well as new houses, as we shall see.

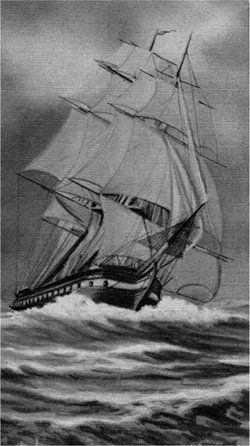

The ships of these merchants also sailed through the Straits of Magellan and up the west coast of South America and on to China, where they traded furs and lumber for silk, tea and porcelain. The China trade began in Boston, where the Columbia was sent to China with a load of ginseng and came back with a boatload of tea. After that, ships went to the Pacific Northwest to buy furs from the Indian tribes and then exchanged those in China for tea or silver, a trade that made the merchants mounds of money.

Shipbuilding prospered, too, on Boston’s docks, and a new type of ship was being built. Troubles with Mediterranean pirates led President Washington to authorize the building of a navy of six frigates. Boston would be the location for the building and launching of one of them. The USS Constitution, a forty-four-gun ship, was built in 1797 in Edmund Hart’s shipyard in the North End and went down the ways, setting sail on Columbus Day of that year. It had an additional Boston connection: its copper bottom plates, spikes and bolts were fashioned by Paul Revere. It set sail for the Mediterranean and won peace from Tripoli under Captain Edward Preble in 1805.

A navy was a new thing, and its formation had to be planned and learned a step at a time. For one thing, it needed leadership. President Washington offered the position of secretary of the navy to Thomas Handasyd Perkins, who would later enjoy the title of “Merchant Prince” in Boston. Perkins would have done well at that job, since he was a fantastic organizer and was held in high esteem, but he had to refuse the honor because he was too busy trading with Rio and China and, in fact, was a man who owned more ships than the government did.

So the fabulous fortunes acquired by this group and the financial growth of the town depended on Boston’s shipping fleet and trade with the West Indies, Europe, China and India.

This “Codfish Aristocracy” also had a strong religious bent. As we enter this period, we find it mired in the dregs of its Puritan-Calvinist traditions where people’s destinies were believed to be pre-ordained. These doctrines left little to self-reliance. The “City on the Hill” that the first settlers visualized relied upon the Lord, while these new Bostonians relied more upon themselves—and succeeded more often than not.

They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters; These see the works of the LORD, and his wonders in the deep. For he commandeth, and raiseth the stormy wind, which lifteth up the waves thereof. They mount up to the heaven, they go down again to the depths: their soul is melted because of trouble. They reel to and fro, and stagger like a drunken man, and are at their wits’ end. Then they cry unto the LORD in their trouble, and he bringeth them out of their distresses. He maketh the storm a calm, so that the waves thereof are still. Then are they glad because they be quiet; so he bringeth them unto their desired haven. —Psalms, 107:23–30, King James Version

However, the Lord did not always still the waves made by storms or the storms made by politics. Use of the seas and of shipping could be a fickle and sometimes dangerous thing. After the war, the British had closed West Indies trade to American ships. Then a maritime depression in the early nineteenth century harmed trade and became one of the factors that led wealthy Bostonians to want to diversify and tap into other streams of income.

A new type of sailing ship was built in the East Boston shipyard of Donald McKay. It was long and sleek and carried clouds of sails. Thus the name Flying Cloud was given to the first of these “clipper ships.” Others followed: Glory of the Sea, Great Republic and Sovereign of the Sea. Long and sleeek, these were some of the fastest sailing ships ever to float. They also had cavernous holds and could accommodate large cargoes to and from the West Coast and China. Their heyday was short, however, since steam power was the future for all kinds of transportation.

Among the merchants, the Perkins family were leaders. They were merchants before the Revolution, and a number of them had been Loyalists or Tories. During the Revolution, three members of the family fled the country and continued their political and business connections within the British Empire.

Thomas Handasyd Perkins, “Boston’s merchant prince.”

Thomas Handasyd Perkins, or T.H.P., was probably the best known of the family. As a boy, T.H.P. had listened to the reading of the Declaration of Independence from the balcony of the (Old) State House on State Street. After the Revolution, he remained in America and took advantage of his family’s business connections, first in the trade with the West Indies, including the slave trade.

But that was not the extent of his success. For a while, the Perkins family were major players in the China trade. At first, that meant trading with the Indians along the Columbia River between today’s Washington and Oregon in the northwestern United States for hides and furs. These were then taken to China and exchanged for tea, spices and porcelain, much desired by their fellow Brahmins back in Boston. They also made piles of money by lending it at high rates both in China and this country. But when the usual China trade fell off, they looked for something different.

One of those family members who had fled Boston was George Perkins, who became a merchant of the British Empire in Smyrna, Turkey. He made a connection with dealers who supplied Turkish opium. Through this connection, he, and his family in Boston, found a way around the monopoly on the opium trade to China that was held by the British East India Company. The Perkins family thus became opium traders.

T.H.P. later did other things that made people forget his darker deeds. He was among those who helped erect the Bunker Hill Monument and was a founder of the Granite Railway in Quincy, used to bring granite for the monument to the edge of the water to be shipped to Charlestown, where it was used for the monument.

He also donated his home in Boston for a school for the blind that became the Perkins School. He was a major benefactor for the school and also a friend of Alexander Graham Bell, who invented the telephone in Boston. It was Perkins’s money that bought out Bell’s work. John Murray Forbes’s son, William, scion of the family, became president of the American Bell Telephone Company and married the daughter of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Russell Sturgis married T.H. Perkins’s sister, Elizabeth, and joined the firm. His grandson, by the same name, moved to England and became chairman of the Baring Bank, the bank of the British East India Company. The China trade was financed almost entirely by the Baring Brothers Bank in England.

Retiring early, Perkins collected art from around the world and turned his home in Brookline into a veritable art museum, with landscape art on the grounds. When he died, the governor gave the state legislature the day off so that members could attend T.H.P.’s funeral.

The dynasty lived on. John Murray Forbes, a protégé and later partner of T.H. Perkins, earned millions in the China trade before turning, with T.H. Perkins, to railroads, the first of which was the above-mentioned Granite Railway. Captain Robert Bennett “Black Ben” Forbes, a seaworn commodore with strange traditions, built a house on Milton Hill that had portholes for windows and a secret treasure room hidden but connected to the cellar by a secret passage, one that was only discovered by family members seventy-five years after his death.

Boston’s commercial progress was slowed again by “Mr. Madison’s War,” the War of 1812, which followed the stagnating Embargo of Jefferson and then the Non-Intercourse Act of Madison. All of this was quite unpopular in New England, where trade would be stifled. Merchant Nathaniel Appleton saw it this way: “This horrible madness has been perpetrated! We stand gaping at each other, hardly realizing that it can be true—then bursting into execrations of the madmen who have sacrificed us.”

Once they stopped gaping at each other, however, Bostonians found their way around the restrictions and danger. For a while, ships were able to sail and enter other American ports without British interference for a bribe if they could prove they had been loaded before the war began.

The Constitution took part in the naval war and, under Isaac Hull, defeated the British frigate Guerriere off Nova Scotia. A sailor taking part in that battle saw British cannonballs bouncing off the sides of The Constitution and yelled out, “Huzza! Her sides are made of iron!” thus giving the ship the sobriquet by which it is commonly known. In fact, it was constructed of white oak and live oak and yellow resilient woods that repelled rot as well as cannonballs.

“Old Ironsides” also won a victory over HMS Java off the Massachusetts coast, but Captain James Lawrence and the Chesapeake suffered a crushing defeat to HMS Shannon in which he uttered the famous words, “Don’t give up the ship!” as he went to his death. The smoke and sound of cannon fire could be seen and heard from Boston. The ship was given up, but his words endure as the motto of the U.S. Navy.

USS Constitution.

New England Federalists did more than grumble about the war, however. In 1814, the Massachusetts legislature called for a convention of the New England states in Hartford to protest the war and consider steps they might take. During the three-week Hartford Convention, the delegates debated whether to secede from the union or make a separate peace with Great Britain. Moderates won the day and decided to present President Madison with constitutional amendments, which would end the war and advance the mercantile interests of their region.

However, as the delegates got to Washington, D.C., they learned about Andrew Jackson’s victory over the British at New Orleans and the Treaty of Ghent, which had concluded the war. This left the Federalists with egg on their faces and enabled their opponents to call them “The Party of Treason.” It was essentially the end for the party of Adams and Hamilton as an influence on national politics.

This wasn’t the only post–War of 1812 change. The wealthy merchants had begun to feel crowded in their North End and Fort Hill dwellings. Members of the working class were growing in numbers, and there was a desire to find a new neighborhood, one that would appeal to the Brahmins.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

BEACON HILL

Home of the “Sifted Few”

The new wealth of the merchant class brought with it a need to spend some capital on homes for themselves. The wealthy had long lived in the North End or on Fort Hill, but these areas had become crowded with mechanics and those who worked in the shipping trades. They were no longer enclaves of the wealthy, and those peo...