![]()

Chapter 1

THE ENVIRONMENT FOR PROSTITUTION IN NEW ORLEANS

From day one, New Orleans has worn the mark of the scarlet letter, first due to the very poor direction of John Law and his Company of the Indies. Law, a Scotsman, was hired by the king of France with questionable attempts to colonize New Orleans. His very aggressive and thoughtless means of populating the city had criminals and prostitutes brought from France to Louisiana against their will. It’s not surprising that prostitution dug its heels in the city, with such a history of illicitness from its very birth. For the entire early eighteenth century, a priority in the colonization of New Orleans was devising plans to attract women to the city to help hold the attention of the men who would, in turn, create families to colonize the territory. These families would work the land, develop housing and engage in traditional businesses, trade and activities found in any functioning community.

However, a “normal” community was far from how New Orleans could have been characterized. With the development of the port city, and the cast of characters who helped build it, came sketchy attributes. At the time of the Civil War, vice districts had organized in every major United States city, as well as many sparsely populated territories in the Deep South to trade liquor for prostitution and gambling. But there was none like that which had materialized in New Orleans. With downtown New Orleans emerged two all-but-forgotten vice districts that became the wretched forefathers of Storyville and were known at the time as the Vieux Carre and the Swamp. The Vieux Carre sat behind the upper French Quarter where Basin Street met Customhouse (now called Iberville) and Customhouse ran to Franklin and the back end of the area faded into the swampy terrain. The district known as the Swamp festered on the land that is now the Central Business District, the Warehouse District and the Lower Garden District.

In his book Storyville, New Orleans, Al Rose describes the territory as “an incredible jumble of cheap dancehalls, brothels, saloons and gaming rooms, cockfighting pits and rooming houses. A one-story shantytown jammed into a half-dozen teeming blocks, the Swamp was the scene of some eight hundred known murders between 1820 and 1850.”

Police avoided the neighborhood, or rather, they allowed those who entered the Swamp to handle their own affairs. “A man could wander into the Swamp and for the going rate of a picayune [about six cents] obtain a bed for the night, a drink of whiskey, and a woman.” It seems that the men it attracted were the kind who carried little more than six cents, or it would not have lasted long. The lowest of the low passed through the Swamp to spend what little they had on the even more desperate, deteriorated and pitiful who had found themselves stuck in the hell called the Swamp. The Swamp lost some momentum in the late 1850s with a shift of business heading to the other side of the French Quarter.

The very busy port at the end of Esplanade Street created yet another outlet for those who set foot in the city. Gallatin Street, two blocks in totality, became so foul that entire buildings were eventually demolished to erase the stigma of the character of men and women they once housed. Richard Campanella writes in his book Bourbon Street: A History that the short two blocks between Ursulines and Barracks became known as the “thoroughfare.” The seedy section was avoided by any respectable citizen but sought out by those looking for a raunchy and rowdy rendezvous. Campanella references newspaper articles at the time characterizing the women who worked the street with reputations that had those in the city acknowledging them as “the frail daughters of Gallatin Street.” If you mentioned that a woman had a career on Gallatin Street, it was immediately understood what that profession was. The women were pitied and demoralized in general conversation.

Like a moat of solicitous debauchery, the neighborhoods flaunting liquor, gambling and loose women framed the city of New Orleans. Gallatin Street was close to the prime market area with thriving, steady twenty-four-hour traffic that attracted criminals and prostitutes who took advantage of those with fat pockets and the quick jobs and cheap meals found in the neighborhood.

Historian and professor of history at Tulane University Judith Schafer, in her book Brothels, Depravity, and Abandoned Women: Illegal Sex in Antebellum New Orleans, explains that in 1857, the city council passed a sixteen-act piece of legislation known as the Lorette Law, named for what the French call prostitutes. The ordinance helped to push prostitution from the river back to the fringe of the city at Customhouse and Basin, where the law was not in effect. The ordinance was specific to a dedicated geography in which prostitutes would annually be taxed $100 and the head of the house $250. While prostitution was still legal on the second floors of buildings on Gallatin, it was not legal for women to work from the ground floor or stand in their doorways or on the streets in front of their houses. “The spatial restrictions aimed to make the sex trade invisible.” Furthermore, prostitutes were not allowed to coax customers from cafés or coffeehouses.

Rather than pay the tax, the flux of business moved to Customhouse and Basin, where the law was not in effect. Before the Lorette Law, there had been very loose laws regarding prostitution. Primarily, the orders were directed at keeping neighborhoods peaceful and did not focus on the issue of sex for hire. However, the law was immediately attacked by all involved in the business of prostitution, and on a technicality of licensing, it was ruled unconstitutional in 1859, upon which, in New Orleans tradition, a parade was thrown to celebrate. However, this one, profane and in poor spirit, gave the finger to the city as it marched through the streets.

In a new renovation program many years later, the city chose to demolish the then underused buildings that lined Gallatin Street. The area had great potential, but after the brothels had fled the area, the street attracted nothing but vagrants. In 1935, the city demolished all the buildings and gave the area a fresh start. Gallatin was renamed French Market Place and not long after turned into a farmers’ market.

However, the next phase of wickedness was finding its place along the vice district that had been known as the Vieux Carre. Basin Street—whose name comes from the turning basin of the Carondelet Canal, which had been located on the street in the section where it now turns on to Orleans— would soon be known as the iconic “Down the Line,” the row of Storyville brothel palaces. At that time, the brothels were much less than palaces run by madams such as Minnie Ha Ha, Kate Townsend and Hattie Hamilton.

It was only a couple of decades later that a young Josie Arlington found her way to Customhouse Street. The environment was a bit more “civilized” by the time her story began. Yet her time in the profession before Storyville could still be considered rough and dangerous—perhaps just not as barbaric as the era of the Swamp and Gallatin Street.

![]()

Chapter 2

MARY DEUBLER

THE EARLY YEARS

The late 1800s in New Orleans was an exciting time for those in the city. New Orleans had been the most profitable city in America and the third largest. While census information documents the growth of the city slowing toward the latter half of the nineteenth century, the city was still advancing in a variety of ways.

New Orleans had fought its way through a volatile history under John Law, who, in addition to shipping the derelicts to the city, encouraged others to come from Germany and Italy at his invitation, with great anticipation of reaping the fortunes they had been misled to believe were available to them. These immigrants instead found swamps with land that was difficult or impossible to farm. Yet the depressed economic climate in Germany had people looking for alternate homesteads, and tens of thousands of Germans immigrated to New Orleans. The 1840s and early 1850s peaked with German immigrants flooding into the port of New Orleans, joining their family and friends with hopes of making better lives for themselves.

Germans, in fact, have been credited through their hard work in farming land as having greatly contributed to the settlement of New Orleans. A city not far from New Orleans, known as Des Allemands (which means “the Germans” in French), was once owned by John Law. He sold it off to German settlers, a little at a time, making a nice profit for himself. In 1857, the German Society of New Orleans was established in order to help German immigrants become acclimated in the new country.

There has been much speculation over Josie Arlington’s past during her younger years in the city of New Orleans. Born Mary Anna Deubler, she and her two brothers, Henry and Peter, were raised in New Orleans by strict German immigrant parents. A story handed down by her family is that Mary had a definite curfew that was not to be broken. Yet one night at the age of seventeen, she missed that curfew, and in extreme anger, her parents put their foot down and would not let her return to their home. This is also the version told in the book Queen New Orleans (1949), by Harnett T. Kane:

A certain Lobrano took her to dinner and did not bring her home until nearly eleven o’clock. This, of course, could mean only one thing. Her father slammed the door, and, though Josie knocked and knocked, he kept it barred against her. Meanwhile Lobrano was waiting outside. He was afraid he couldn’t support her; but he had another suggestion: She would support him. He knew one or two madams; with his backing, she could do well for herself.

However, Josie told a very different story to her niece Anna Deubler. She claimed that she was orphaned at a young age and forced to live with her mother’s sister, who treated her unfairly. Josie told the same version during a court case later in her life, explaining why she briefly went by the name Schultz, which she says was her aunt’s name. As reported in the Times-Picayune of January 29, 1892, during the trial of her brother’s murder, “My right name is Mary A. Deubler. Was raised by an aunt named Schultz and was once known by that name.”

No one knows to what extent each version is reliable, but these were serious times for Josie and her family, and one way or another, the situation catapulted a young Mary Deubler into a life of prostitution.

Over the years, as mentioned, she went by various aliases, including Mary Nix, Josie Deubler, Josie Schultz, Josie Alton and Josie Lobrano, most likely to protect her family while she worked at various brothels on Customhouse and Basin Streets. The thriving port brought business to the city and, with it, a flurry of sailors who found New Orleans catering to their desire to let loose while at port. Drinking, gaming and women were among the top priorities, allowing prostitution to thrive.

In 1885, Josie is listed in a city directory for prostitution as the head of a home, under the name Miss Josie Lobrano, the surname of her then lover, Philip Lobrano, yet the two were never married. Josie had a strong will and an entrepreneurial nature, and at the time, prostitution was one of the few businesses women had the right to manage. From prostitute to madam, Josie soon ran a brothel on the corner of Burgundy and Customhouse, on the seedier side of the city. The brothels were close to the city’s opium dens and all under the ominous watch of the enormous prison known as the Metropolis.

Josie Arlington sometime in the late 1800s. From the Josie Arlington Collection, courtesy Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans.

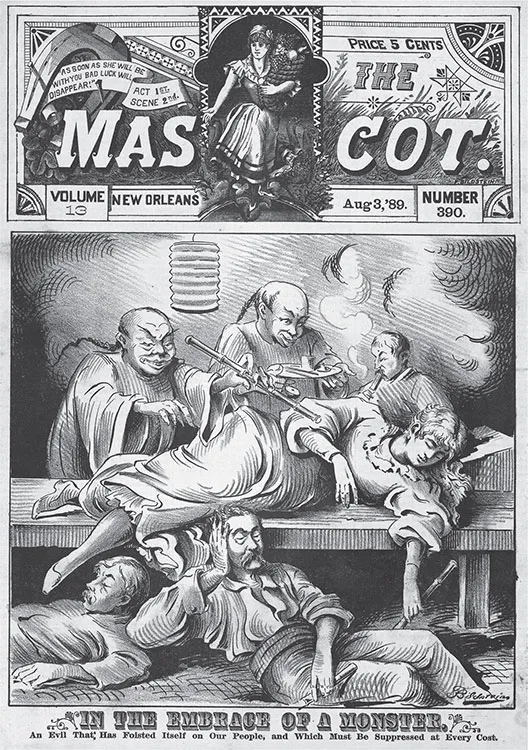

The opium dens were hidden in the Chinese laundromats that lined Rampart Street and other areas of the city. A local rag, or independent journal, the Mascot, published in New Orleans on Saturdays from 1882 to 1897, referenced the cover cartoon in its August 3, 1889 edition:

It would surprise many persons if they only knew to what a frightful extent the opium habit has taken hold in New Orleans. It may not be generally known but a matter of fact, more people in New Orleans are addicted to the enslaving and totally demoralizing habit than in any other city of the union. The opium “joints” flourish in all parts of the city and are patronized by all classes. There locations are known not only by the regular “fiends” but also to many other people besides the police, who are not regular customers. Almost every Chinese laundry in New Orleans is an opium joint, where the lovers of the “pipe” can be accommodated and the wonder is that some determined and positive effort has not already been made to suppress the frightful evil to which so many of our people are enslaved. The Chinese joints are not frequented exclusively by the women of the town as may be generally expected but are liberally patronized by young women and old ones too, who are respectable and move in others than out-cast circles.

Cover of the Mascot, August 3, 1989. Courtesy Tulane University Special Collections, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University.

It was easy to find what you wanted in the city of New Orleans in all forms of vices. Not even the vast metropolis of a building that was erected in the 1880s, where the New Orleans public library stands today, could threaten those driven to find decadence. The building served as the city’s criminal court and parish prison. Towering over the debauchery below, it housed three hundred prison cells for men and fifty for women, offices for the judges, the courthouse, a chapel and a yard where hangings were performed.

The city that was born under the corruption of John Law continued the tradition. When the Orleans Parish Criminal Court building was erected in the 1880s, it quickly began to crack and creak. Floors shifted and walls splintered. At first, those in charge chalked it up to the soft soil of New Orleans and the high water table. However, not long after it was discovered that the very individuals in charge of building the structure had cunningly cut corners and, in good old New Orleans fashion, filled their pockets instead of putting the money where it belonged. They were all arrested, and poetic justice had them placed in the prison they had built. Nicknamed “The Metropolis” for its ominous Gothic beauty, the building sadly lasted only forty years.

The climate in New Orleans for indulgence was so great that justification for vices became greater than the threat of tainting the good people of the city. Even the law found it hard to keep hands out of the cookie jar. A few police officers found their way to corruption among the corrupt. In fact, a court case was filed against two officers, Patrick J. Bell and John P. Bayhi, in 1893 for blackmailing prostitutes. They were offering their “protection” for weekly payment, reportedly around two dollars per prostitute. The scandal shook up the police force with allegations of not just those officers but against the entire force, including “greatly incompetent men among its commanding officers.”

Feeling vindicated in the acknowledgement of a crime against them, the prostitutes of the city showed up in full force. An article published on September 1, 1893, paints a wonderful picture of the scene, with everyone gathering for a day in court:

Old Orleans Parish Criminal Court and Old Parish Prison. Courtesy Southeastern Architectural Archive, Special Collections Division, Tulane University Libraries.

The room filled with a motley assembly. The corridors in the immediate vicinity of the Council Chamber were thronged. Men and women were there, the men mostly as spectators, the women all as witnesses.

Outside the hall the scene presented almost resembled that outside the French Opera House of a winter’s night. Lamps flashed in long rows up and down the street. Stamping horses attached to carriages and cabs waited for hours for the women inside the building.

In the council chamber itself the scene while scarcely to be dignified by the term brilliant, was a gaudy one in the extreme.

It was described as an event so extraordinary that one like it would hardly grace the courthouse again. One can only imagine the cast of mixed-up characters coming to say their piece, parading through the courthouse halls in impossible costumes:

There were women dressed in all the colors of the rainbow. They were dressed in rustling silks and satins, they were dressed in rags. Costly diamonds flashed and glittered from ears and arms, from bosoms and from fingers; disease and dirt showed itself plainly on countenance and figure, on dress and manure.

Women old and women young, women white and women black, painted...