- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

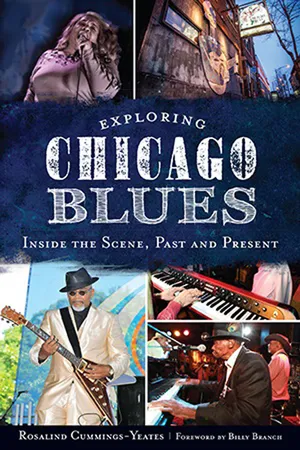

Discover the living legacy of Chicago Blues in this guide to the iconic clubs and musicians who made—and keep making—music history.

During the Great Migration, African Americans left Mississippi for Chicago, and they brought their music traditions with them. The music took root in the city and developed its own distinctive sound. Today, Chicago Blues is heard all over the world, but there's no better place to experience it than in the city where it was born.

In Exploring Chicago Blues, Chicago music writer Rosalind Cummings-Yeates takes you inside historic blues clubs like the Checkerboard Lounge and Gerri's Palm Tavern, where folks like Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Willie Dixon and Ma Rainey transformed Chicago into the blues mecca. She then takes you on an insider's tour of the contemporary blues scene, introducing the best spots to hear the purest sounds of Sweet Home Chicago.Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

CHICAGO BLUES HISTORY

1

From Mississippi to the Windy City

The Great Migration and the Blues

The roots of Chicago blues music don’t actually start with a particular song or musician. The beginnings of this highly emotional art form can be traced to the imposing mechanical presence of a train. The Illinois Central Railroad, dubbed “the IC” by Chicago residents, transported the blues to Chicago in the form of Mississippi migrants who carried their musical traditions with them. Thousands hopped onto these trains, the most famous of which was the Panama Limited, that supplied service between Chicago, St. Louis and New Orleans. The passengers included sharecroppers, field hands, carpenters and masons searching for the expanse of northern opportunities that would bring them freedom and equality. They braved twelve- to twenty-four-hour journeys in what would be called the Great Migration.

This migration of African Americans from the South to the North helped develop what would become known as Chicago blues. Starting around the beginning of World War I, masses of southern blacks moved north to escape brutal Jim Crow laws and ravaged cotton crops. They migrated to big northern cities to seek the promise of more economic opportunities and an existence free from lynchings and the inequality of Jim Crow laws. The war in Europe halted the European immigration that had supplied labor for northern factories, so northern businessmen eagerly recruited black workers from the South. These were the circumstances that drew hordes of Mississippians to Chicago during the beginning of the Great Migration, filling the South and West Sides of the city and laying the foundation for the creation of Chicago blues.

A stone left behind from the Illinois Central Railroad. Author’s collection.

“The blues may have started in the South but it developed into a sophisticated art form in Northern cities,” explains Sterling D. Plumpp, poet laureate of Chicago blues and professor emeritus at the University of Illinois–Chicago. Plumpp participated in the later half of the Great Migration, catching the IC from Mississippi to Chicago in 1961. Landing in the bustling West Side neighborhood of Lawndale and, later, the South Side enclave of Woodlawn, Plumpp walked to popular neighborhood joints to catch Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and Lightnin’ Hopkins playing to small crowds of regulars. He recognized the blues rhythms that had surrounded him growing up in Mississippi, but they had taken on a smoother, electrified sound in Chicago.

The Mississippi and Chicago connection was a crucial factor in the creation of Chicago blues. The Mississippi Delta blues that musicians played on plantations, in juke joints and at gatherings throughout the South was a blueprint for what would become the Chicago blues. Typically played with acoustic guitar and harmonica, the Delta blues sound traveled to Chicago as migrants from rural Mississippi, where the blues was formed, flooded the city. Although people also came from other southern states, figures show that the majority of African Americans arriving in Chicago during the Great Migration moved from Mississippi. In Mike Rowe’s 1975 exploration of Chicago blues, Chicago Breakdown, Mississippi stands out as the most frequent home state for thousands of migrants during the heart of the Great Migration: “from the best estimate, the net intercensal migration to Chicago for the years 1940–1950 was 154,000 and something like one-half of these migrants were born in Mississippi.”

THE URBAN BLUES

Chicago represented the most direct route from the Delta to the north on the IC, and by the late 1930s, it was also the place where the most popular blues records were recorded. During the ’20s and early ’30s, record labels such as Okeh and Paramount organized field trips to the South to record the sparse, rhythmic patterns of the country blues. Sometimes the labels would bring the musicians to Chicago or New York to record, but more typically, they captured the music in its natural setting, among plantations, crumbling shacks and a vicious caste system that fueled the emotional blues laments.

A steady stream of blues musicians settled in Chicago during the beginning of the Great Migration, and they adapted their music to their new environment. The straightforward guitar and harp accompaniment of country blues evolved into piano and guitar tunes, revealing a more urban sophistication. The influences from crowded tenements and fast-paced city living seeped into the music, altering the tone and arrangements. The move away from rural fields, where the mobility of instruments was important, is reflected in the addition of the stationary piano, a popular feature in most city clubs and taverns. By the 1920s, this new blues sound was being recorded by Chicago record labels. “Blues singers came from the agricultural class. They were used to the style they sang in the fields,” says Plumpp. “They created the music, the clubs and the scene.”

The most significant Chicago “race” record label at the time was Bluebird, run by Lester Melrose, who, according to Chicago Breakdown, shaped the recorded Chicago blues sound into a consistent lineup of singer, guitar, piano, bass, drum and an occasional harmonica or sax. Race records were aimed specifically at the new African American market of music fans, eager to hear the new urban blues. Not only was the sound different than the stark shouting of the country singers, but the mood was also different. Big Bill Broonzy, one of the pioneers of the new urban blues, sounded exuberant on his recordings. He transitioned from playing country blues on his acoustic guitar to being backed by his Memphis Five, which supplied an up-tempo sound that mixed popular dance music with blues. By the late ’30s, Chicago blues had a distinct sound and mood that reflected the sensibilities of the Great Migration travelers who had settled in the city. Austin Sonnier explains in A Guide to the Blues: History, Who’s Who, Research Sources:

Departing from the ease and subdued temperament of the blues that went before, the emotional level of blues in Chicago in the late 1930s and early 1940s was beginning to pick up. By that time the city’s black population had established its own cultural roots, and there began a new feeling of assertion in the music. Different instrumental combinations sprung up. Melodic and rhythm patterns changed, and off beat accents became popular. Vocal acrobatics also added greatly to a new musical excitement. All of these elements generated a strong sense of social cohesion and power among blacks.

The emotional pain of the blues was quieted with a focus on the lively band rhythms. It was as if the prospect of better opportunities and rest from backbreaking labor seeped out from the music and inspired southern listeners to seek out the northern Promised Land. Of course, the reality of this storied city was much different than the hopeful dreams of southern migrants.

The first stop for musicians landing in Chicago was Maxwell Street. Called “Jew Town” because of the large numbers of Eastern European Jewish vendors who dominated the market with pushcarts, the open-air market was centered on Maxwell and Halsted Streets. A hodgepodge of cheap clothes, used furniture, appliances, produce, handicrafts and street food served as the backdrop for the blues streaming out of the market. Musicians stood on corners, in between sellers’ tables—anywhere they could find to draw a crowd. By the ’40s, they had started to hook up amplifiers so their blues sound could carry across the crowded market. Playing on Maxwell Street served as an introduction to the Chicago blues scene; before the musicians could win a club gig or a record contract, they’d get their feet wet on Maxwell Street. Many blues musicians traveled from the South specifically to play on Maxwell Street. According to legendary Chicago blues musician Honeyboy Edwards’s autobiography, The World Don’t Owe Me Nothing, “I remember when musicians walked from Memphis, Arkansas, and Mississippi with their guitars on their shoulders because they found out they could make some money on Maxwell Street!”

After establishing a following on Maxwell Street, blues musicians could parlay that into playing in the blues clubs that blanketed the South and West Sides of the city. An array of clubs represented the chance to make more money than the musicians had ever seen on southern plantations and in rural towns. It also presented opportunities to play on stages before appreciative, dancing crowds. The best, most popular clubs were all located in the neighborhood where the recent African American migrants were forced to settle. Called the “black belt” and the “black metropolis,” the area was teeming with dilapidated tenements, as well as elegant brownstones and nightclubs. This was where the southern transplants faced the northern brand of segregation and racism. Stretching across a narrow strip of Chicago, the area was also famously called Bronzeville.

2

The Black Belt of Bronzeville

The numbers of African Americans fleeing the South and flooding into Chicago during the Great Migration were unprecedented. According to Isabel Wilkerson in her chronicle of the Great Migration, The Warmth of Other Suns, “World War II brought the fastest flow of black people out of the South in history—nearly 1.6 million left during the 1940s, more than any decade before.” Bronzeville originally unfolded from Sixteenth Street to Thirty-ninth Street in 1900, forming a long, narrow, belt-like shape. By 1930, the thousands of new arrivals had pushed the area from Sixteenth Street to Sixty-seventh Street. The misery that the overcrowded, overpriced conditions created was observed by Edith Abbott, a researcher at the nearby University of Chicago who studied tenement life in the city in the 1930s. As Wilkerson explains, according to Abbott, “Families lived without light, without heat and sometimes without water…The rents in the South Side Negro districts were conspicuously the highest of all districts visited.” If that weren’t enough, the migrants were met with the same racism, and sometimes violence, from which they had fled in the South. A notorious riot broke out in 1919 when a black boy swam across the invisible line separating the black side from the white side of the beach. In another infamous Chicago incident in 1951, a black family who dared to leave Bronzeville to move into an apartment in Chicago’s Cicero suburb had their furniture and belongings torched and their building firebombed.

These are the factors that helped create Bronzeville, an area of the city where African Americans were segregated and forced to create their own businesses since they weren’t welcome downtown. So they opened their own restaurants, grocery stores, doctor’s offices and even a large department store, South Center. At night, the main strip of Forty-seventh Street was lit up with nightclubs and lounges, including the Regal Theatre, 708 Club, the Parkway Ballroom, the Boulevard Lounge, the Savoy, Square’s and Gerri’s Palm Tavern. These were the venues where the southerners played the songs that had helped soothe the pains of southern injustice. Now, the music gave solace in a cold and unfriendly city with its own kind of injustice. Inside these dance halls and bars, which were basically urban juke joints, acoustic strains of country blues evolved into the electric rhythms of what would eventually be dubbed Chicago blues.

Playing Maxwell Street was an easy introduction to the city. It was similar to playing the corners and country stores in rural towns; you just grabbed a spot and started to play. But performing inside a Bronzeville club or lounge was a different story. Typically, new musicians would get their starts by sitting in with the established musicians. Owners would hear them and book them at their clubs, initiating them onto the slippery road to a big-city musician’s career. Mike Rowe explains the blues club setup through the experience of legendary Chicago bluesman Homesick James in Chicago Blues: The City & the Music:

Homesick was working with Horace Henderson’s mixed group at Circle Inn, 63rd and Wentworth, and at the inappropriately named Square Deal Club, 230 W. Division Street, with the pianist Jimmy Walker. They played for five or six hours, mostly Blind Boy Fuller and Memphis Minnie numbers, for three dollars each. This was always the pattern, for, with the long-established artists like Big Bill, Tampa Red and Memphis Minnie playing regularly at the bigger clubs, it was very hard for newcomers to break into the scene, although most of the well-known singers were always willing to lend a hand to the young hopefuls from the South.

This was the environment that spawned the birth of Chicago blues. Crammed into the designated black areas of the South and West Sides, the new arrivals re-created the comforts of their southern homes in Chicago. They brought their barbecue and ham hocks, their church rituals and their music. The simple acoustic guitars and personal laments were altered by the big city and grew into bands with not just guitar and harmonica but also bass guitar, drums, piano and sometimes saxophone. The music was amplified to be heard over the rowdy bar crowds, and the lyrics expanded to encompass broader, urban experiences. And they called it Chicago blues.

3

Chicago Blues Papas

The names and talents of all the musicians who have influenced and helped develop Chicago blues could fill a small library. This section will not attempt to identify all of these musicians. Instead, this small group represents the bluesmen who left a recognizable and unquestionable mark on the genre. These are the names that even the most casual Chicago blues fan should know. In order to understand Chicago blues, it helps to know a little about all of these historic musicians.

BIG BILL BROONZY

A legendary figure whose prolific songwriting and guitar playing helped shape the Chicago blues sound from the 1930s through the late ’50s, Big Bill Broonzy was a highly versatile musician with lasting influence. He started out with the acoustic country blues he heard growing up in Arkansas, playing the box fiddle and violin. He didn’t learn guitar until arriving in Chicago in 1920, crafting a dexterous finger-picking style that he easily adjusted to the setting and style the situation required. Big Bill played guitar for pivotal Chicago blues artists, including Georgia Tom Dorsey, Tampa Red and Memphis Minnie, but it was his years recording and writing for Chicago’s legendary Bluebird Records that would firmly establish his legacy.

Bluebird Records was a Chicago label that recorded the majority of blues artists during the ’30s and through the early ’50s. Most of these performers didn’t have their own backup bands, so Bluebird’s owner, Lester Melrose, decided to have these same musicians play on one another’s records. The result was the “bluebird beat,” which Big Bill helped create by playing guitar on hundreds of records. Characterized by upright bass and trap drums, the bluebird beat was the sound of a newly developed urban blues, which would evolve into the postwar Chicago blues sound. Big Bill didn’t just play on the records; he also worked as Melrose’s co-manager, organizing recording sessions, scouting talent and writing songs, deepening his impact on this new blues style.

As a man of so many talents, it’s hard to narrow Big Bill’s most significant legacy, but his songwriting and storytelling skills were unmatched by anyone in his era. The author of at least one hundred original blues songs, he wrote classics like “Key to the Highway,” “Unemployment Stomp,” “Digging My Potatoes” and his most controversial, “Black, Brown and White,” a stinging narrative on racism. His evocative storytelling abilities reached into his personal life, which he treated as an extension of his music. He related accounts and sang songs of growing up in rural Mississippi, the son of slaves. It’s only recently that researchers have discovered that neither of these points was true; even his name was made up. He changed and re-created realities that best suited the situation. Toward the end of his life, when folk music became popular as a tool for social change, he reinvented his show and included folk songs, creating a second act in a long and ever-changing career. He paved the way for the next generation of blues performers to adapt to the changing musical landsca...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I: Chicago Blues History

- Part II: Chicago Blues Now

- Bibliography

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Exploring Chicago Blues by Rosalind Cummings-Yeates in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.