![]()

Chapter 1

OPENING MOVES

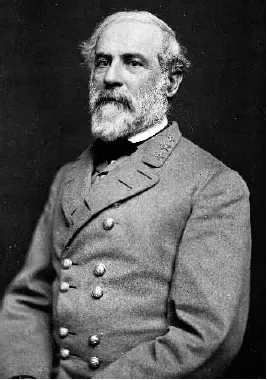

Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia thrashed Joseph Hooker’s Union Army of the Potomac at the Battle of Chancellorsville, fought May 1–5, 1863. The spring campaign had begun inauspiciously. The Army of the Potomac broke its winter camps and began marching on April 27. Three Federal corps, the Fifth, Sixth and Twelfth, marched to Kelly’s Ford, crossed the Rappahannock River and swung southeast toward Germanna Ford on the Rapidan River. The Federal Third Corps remained at Falmouth, while the First and Sixth Corps started moving toward the Rappahannock crossings at Fredericksburg. Thus, Hooker had more than 133,000 blue-clad infantrymen in motion by the afternoon of April 28.

By the night of April 29, Major General George G. Meade’s Fifth Corps was poised to enter the Wilderness from Ely’s Ford on the Rapidan, while Major General Darius N. Couch’s Second Corps crossed the Rappahannock at U.S. Ford and moved toward Chancellorsville, a handsome tavern situated at a critical road intersection on Lee’s left flank. By the night of April 30, four Union infantry corps were concentrated around Chancellorsville, ready to move against Lee’s exposed flank. Lee did not know they were there and was unprepared to fend them off, as his attention was focused on the large force in front of Fredericksburg. However, instead of pressing his advantage, Hooker halted and ceded the initiative to the wily Lee, who shifted most of his army to meet the threat once he became aware of it.

Major General Joseph Hooker, commander of the Army of the Potomac. Library of Congress.

The battle around Chancellorsville began in earnest on May 1. Hooker’s troops attacked the outnumbered Confederates of Lieutenant General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s Second Corps and shoved them back. Union infantry took possession of commanding high ground east of Chancellorsville. However, over the vehement objections of his subordinates, Hooker abandoned the strong position taken by his troops that day and instead pulled back to a defensive position at Chancellorsville, where he waited for Robert E. Lee to attack him.

That attack came on the afternoon of May 2. Lee gambled, dividing his outnumbered force and sending Jackson and the Second Corps on a seventeen-mile flank march, leaving fewer than twenty thousand men to contend with Hooker at Chancellorsville. In spite of warnings and evidence indicating that Jackson’s corps was on the move, Hooker refused to act. The Confederate infantry crashed into the exposed and unprotected Eleventh Corps flank and broke it, sending its routed elements streaming back toward Chancellorsville late in the afternoon. That night, while out scouting, Jackson was shot by his own troops. He died a few days later. However, his flank attack shattered Hooker’s confidence and cast the die for the Army of the Potomac’s campaign in the Wilderness.

Hooker pulled back into a tight defensive position centered on Chancellorsville. On the morning of May 3, Jackson’s weary infantrymen, now commanded by Major General J.E.B. Stuart, the Army of Northern Virginia’s cavalry chief, resumed the assault on Hooker’s left. About nine o’clock that morning, a Southern artillery shell struck the porch where Hooker stood, stunning and probably concussing the army commander, leaving him incapacitated. Couch, the senior corps commander, found himself in de facto command of the Army of the Potomac, and he fought a superb defensive action against Jackson’s determined veterans, who were joined by the rest of Lee’s army. Couch was wounded twice in the action, and his horse was shot out from under him. The Army of the Potomac withstood the onslaught with heavy losses.

Meanwhile, the Union Sixth Corps crossed the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg and drove the Confederate defenders from their strong position along a sunken road at Marye’s Heights. They pressed westward, hoping to link up with Hooker from the east, but a stout stand by Major General Lafayette McLaws’s Confederate infantry at Salem Church on May 4 repulsed this attack, preventing the Sixth Corps from reinforcing the Union position at Chancellorsville. Southern reinforcements then drove the Sixth Corps back toward Fredericksburg, ending any hope of linking up with the Army of the Potomac’s main body.

General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia. Library of Congress.

By now thoroughly beaten, Hooker pulled back into prepared defensive positions around the Chancellor House, with both of his flanks anchored on the banks of the Rappahannock River. The two battered armies spent May 5 glaring at each other, but there was not much fighting. On the morning of May 6, Hooker finally admitted defeat and began pulling the Army of the Potomac back across the Rappahannock at U.S. Ford. The Federals returned to their jumping-off point near Falmouth. Lee let them go, knowing that his outnumbered army had already accomplished as much as he might have hoped. Hooker’s magnificent campaign, which had begun with so much hope, ended with a fizzle, a victim of the commander’s hesitation at the critical moment on May 1.1

Having seized the initiative from Hooker, Lee wanted to gamble again. The Confederate high command convened a series of meetings in Richmond to discuss the next moves after the epic victory at Chancellorsville. After three days of intensive dialogue, Lee persuaded the Confederate leadership that the time had come for a second invasion of the North. Confederate secretary of war James A. Seddon later reported that Lee’s opinion “naturally had great effect in the decisions of the Executive.”2 A northward thrust would serve a variety of purposes: first, it held the potential of relieving Federal pressure on the beleaguered Southern garrison at Vicksburg; second, it would provide the people of Virginia with an opportunity to recover from “the ravages of war and a chance to harvest their crops free from interruption by military operation”; third, it would draw Hooker’s army away from its base at Falmouth, giving Lee an opportunity to defeat the Army of the Potomac in the open field; and finally, Lee wanted to spend the summer months in Pennsylvania in the hope of leveraging political gain from such an invasion.

With his bold plan approved, Lee returned to his army and began making preparations for the coming campaign. All seven brigades of cavalry assigned to the Army of Northern Virginia began concentrating in Culpeper County in anticipation of the campaign’s opening. That concentration of cavalry proved to be an irresistible target for its Federal counterparts, who remained active and diligent, looking for opportunities to strike a blow.

On May 14, reports of Confederate raiders in Hooker’s rear brought action. With a ten-year-old boy named Bertram E. Trenis as their guide, elements of seven Northern mounted units set out to pursue the marauders, rousting a group of Southern guerrillas in the process. Major J. Claude White of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry led the pursuit, scouting the country to and around Brentsville. The Federals took a few prisoners, killing three horses and inflicting severe wounds on several enemy troopers with saber cuts.3

Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton, commander of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps in June 1863. Library of Congress.

On May 17, Lieutenant Colonel David R. Clendennin’s Eighth Illinois Cavalry received orders to go out on a lengthy reconnaissance into the so-called “Northern Neck” between the Rappahannock and Potomac Rivers in King George, Westmoreland, Richmond, Northumberland and Lancaster Counties.4 Clendennin divided his command into three battalions, which traversed the entire length of the Neck, making their way to the confluence of the two rivers. They arrived at Leed’s Ferry and determined that it was used for smuggling contraband across the Rappahannock. Clendennin decided to destroy the ferry. Six of the Illinois saddle soldiers dressed themselves in gray, took two prisoners with them and called out to the men on the opposite bank to bring the boat across. The deception worked famously, and when the ferrymen brought the boat across the river, they were promptly captured and the boat burned.5

Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton, who assumed temporary command of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps when its regular commander, Major General George Stoneman, left the army to take medical leave on May 15, 1863, reported that the Illini horsemen

destroyed 50 boats, and broke up the underground trade pretty effectually, having destroyed some $30,000 worth of goods in transit. They bring back with them 800 contrabands, innumerable mules, horses, &c., and have captured between 40 and 50 prisoners, including a captain and lieutenant.

Pleasonton claimed that his horse soldiers caused more than $1 million in damage to the enemy war effort at the cost of one man severely wounded and two slightly injured. “Considering the force engaged and the results obtained, this is the greatest raid of the war,” boasted Pleasonton.6 The regimental historian of the Eighth Illinois noted:

It was found that some of the wealthiest citizens on “the neck” were engaged in the smuggling business, or contributing in some way to the support of the rebellion; and these gentlemen were made to pay dearly for their secession sympathies.7

Several infantry regiments also accompanied this expedition, raiding deep into the heart of Virginia. Captain George H. Thompson’s squadron of the Third Indiana Cavalry joined them, making a lengthy march and successfully completing a dangerous crossing of the Rappahannock in leaky boats. The Northern saddle soldiers covered forty-five miles in just five hours that day. “We hid in the woods till next morning,” reported Captain George A. Custer of the Fifth U.S. Cavalry, of Pleasonton’s staff, who accompanied the expedition. “With 9 men and an officer in a small canoe I started in pursuit of a small sailing-vessel.” They pursued for nearly ten miles until the Southerners ran their boat aground, jumped overboard and ran for the shore. “We captured boat and passengers,” continued Custer. “They had left Richmond the previous morning and had in their possession a large sum of Confederate money.”

Custer and a handful of men waded ashore and headed for the nearest house. Custer spotted a man in Confederate uniform lying on the piazza, reading a book. Although worried that he might be falling into a trap, Custer took the man prisoner.

Then, with twenty men, in three small boats, I rowed to Urbana on the opposite shore. Here we burned two schooners and a bridge over the bay, driving the rebel pickets out of town. We returned to the north bank where we captured 12 prisoners, thirty horses, two large boxes of Confederate boots and shoes, and two barrels of whiskey, which we destroyed.

Custer captured two horses himself.8

The Hoosiers successfully completed their march, capturing a handful of prisoners, a stash of Confederate money and fifteen horses, which they turned over to Pleasonton.9 Custer, a scant two years out of West Point, was beginning to attract attention with his exploits. Hooker sent for him and complimented him highly on his conduct of the expedition, saying that it could not have been done better and that he would have more for Custer to do.10

Several days later, Michigan governor Austin Blair visited the camps of his state’s troops. The colonelcy of the Fifth Michigan Cavalry was vacant, and Custer craved it. Custer asked Pleasonton to write a letter of recommendation for him, something that Pleasonton happily did. “Captain Custer,” wrote Pleasonton,

will make an excellent commander of a cavalry regiment and is entitled to such promotion for his gallant and efficient services in the present war of rebellion. I do not know anyone I could recommend to you with more confidence than Captain Custer.

Hooker gladly endorsed the recommendation. “I cheerfully concur in the recommendation of Brig Genl Pleasonton. He is a young officer of great promise and uncommon merit.”11 Although the ap...