- 209 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

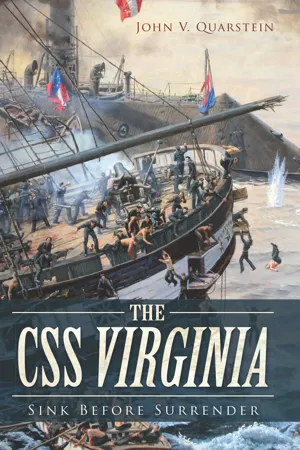

This history of the Confederate Navy's ironclad warship " will likely be the definitive single title on the CSS

Virginia" (

Civil War News).

When the CSS Virginia—formerly the USS Merrimack—slowly steamed down the Elizabeth River toward Hampton Roads on March 8, 1862, the tide of naval warfare turned from wooden sailing ships to armored, steam-powered vessels. Little did the ironclad's crew realize that their makeshift warship would achieve the greatest Confederate naval victory.

The trip was thought by most of the crew to be a trial cruise. Instead, the Virginia's aggressive commander, Franklin Buchanan, transformed the voyage into a test by fire that forever proved the supreme power of iron over wood. The Virginia's ability to beat the odds to become the first ironclad to enter Hampton Roads stands as a testament to her designers, builders, officers, and crew. Virtually everything about the Virginia's design was an improvisation or an adaptation, characteristic of the Confederacy's efforts to wage a modern war with limited industrial resources. Noted historian John V. Quarstein recounts the compelling story of this ironclad underdog, providing detailed appendices, including crew member biographies and a complete chronology of the ship and crew.

Includes illustrations

When the CSS Virginia—formerly the USS Merrimack—slowly steamed down the Elizabeth River toward Hampton Roads on March 8, 1862, the tide of naval warfare turned from wooden sailing ships to armored, steam-powered vessels. Little did the ironclad's crew realize that their makeshift warship would achieve the greatest Confederate naval victory.

The trip was thought by most of the crew to be a trial cruise. Instead, the Virginia's aggressive commander, Franklin Buchanan, transformed the voyage into a test by fire that forever proved the supreme power of iron over wood. The Virginia's ability to beat the odds to become the first ironclad to enter Hampton Roads stands as a testament to her designers, builders, officers, and crew. Virtually everything about the Virginia's design was an improvisation or an adaptation, characteristic of the Confederacy's efforts to wage a modern war with limited industrial resources. Noted historian John V. Quarstein recounts the compelling story of this ironclad underdog, providing detailed appendices, including crew member biographies and a complete chronology of the ship and crew.

Includes illustrations

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

eBook ISBN

9781614238355Subtopic

American Civil War History1

“A Magnificent Specimen of Naval Architecture”

Admirals throughout the world took serious notice on November 30, 1853, when the Russian Black Sea Fleet, under the command of Admiral Pavel Stepanovich Nakhimov, attacked a Turkish squadron off Sinope. The Russians, armed with guns firing explosive shells, utterly destroyed the Turkish wooden vessels. It was the first major naval engagement of the Crimean War and set in motion a revolution in ship design, culminating in the development of armor-clad warships. The engagement at Sinope sent a telling message to naval leaders: wooden ships could not withstand the destructive power of explosive shells. While the Europeans began their transition to an iron navy during the Crimean War with the construction of ironclad floating batteries, the U.S. Navy was slow to recognize the need to construct armored warships. Nevertheless, the United States, faced with the need to protect overseas economic interests and seaborne trade, sought to modernize its navy. The result would be the construction of six steam screw frigates, one of which was the USS Merrimack.

Thus, the story of the CSS Virginia actually begins on April 6, 1854, when the United States Congress authorized Secretary of the Navy James C. Dobbin to construct “six first-class steam frigates to be provided with screw propellers.”1 This new class of frigates was intended to be superior to any other warship in the world. Each was named in honor of an American river: Merrimack, Wabash, Colorado, Roanoke, Minnesota and Niagara. John Lenthall, chief of the United States Bureau of Naval Construction, was ordered to develop the overall concepts for the new class. Lenthall, called “the ablest naval architect in any country,” designed the frigates to operate primarily under sail.2 Steam engines were considered as auxiliary while entering port, during storms or when maneuvering in battle. Lenthall completed his plans on June 27, 1854, and forwarded them to Charlestown Navy Yard, near Boston, Massachusetts, where the first frigate, the Merrimack, would be built.

John Lenthall, Chief, U.S. Navy Bureau of Naval Construction, engraving, circa 1855. Courtesy of John Moran Quarstein.

The Merrimack’s keel was laid on September 23, 1854. Construction was supervised by Commodore Francis Hoyt Gregory, commandant of the Charlestown Navy Yard, and directed by the yard’s naval constructor, Edward H. Delano. Even though the Merrimack was considered a trial ship, nothing but the finest materials available were used in her construction. Her frame was constructed of live oak, originally procured for more traditional sailing warships, and she was built for speed under sail. Her hull was rather sheer but of traditional design. The only difference from a typical sailing warship of the era was her overhung stern. This design modification was necessary to accommodate the propeller, as there was a gap of more than six feet between the sternpost and rudderpost.

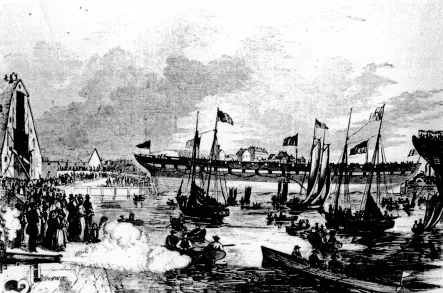

The Merrimack was launched on schedule on June 14, 1855. It was a grand affair with over twenty thousand spectators on hand to witness the event. The decks of the old ships of the line, USS Ohio and USS Vermont, were reserved for dignitaries, while others crowded along bridges and docks and aboard the estimated one hundred ships in the harbor to gain a view of the ceremony. Miss Mary E. Simmons, daughter of Master Carpenter Melvin Simmons, USN, sponsored and christened the Merrimack. In honor of the American Temperance Society (which had been founded in Boston in 1826), Miss Simmons christened the frigate with a bottle of water from the Merrimack River rather than the more traditional champagne. A thirty-one-gun salute, one for each state of the Union, was fired as the Merrimack slid down the ways into her “destined element” at 11:00 a.m. and “shot out into the stream about half way to East Boston before stopping.” The crowd reacted with “enthusiastic huzzas” as the frigate glided into the harbor. The Boston Daily Evening Transcript noted that the affair was “altogether the most beautiful and perfectly artistic” launch ever witnessed in Boston. The Transcript added a postscript that while “the Merrimac is in Dry Dock there will be a good opportunity for strangers and others to examine this new and important addition to our naval force.”3

Launching of the Merrimack, engraving, 1857. Courtesy of John Moran Quarstein.

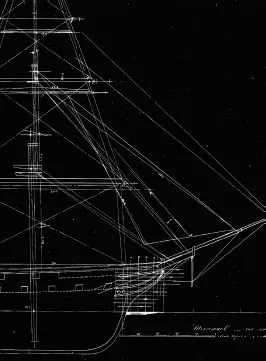

The Merrimack was then masted and rigged for sails. Her mainmast was 242 feet in length, divided into four sections. The foremast and mizzenmast were stepped in proportion. The frigate was designed to be fully rigged, with the area of ten principal sails being about thirty-two times the immersed midship section.4 The Merrimack could unfurl 48,757 feet of canvas.

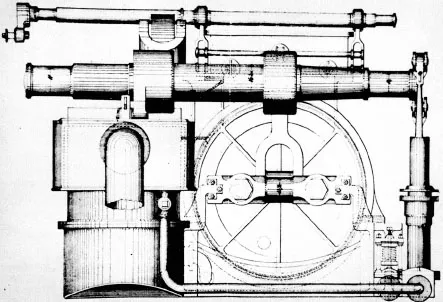

On July 21, 1855, the Merrimack’s machinery began to arrive at the navy yard for installation. The engines were designed by Robert Parrott and built at West Point Foundry in Cold Springs, New York. Two horizontal, back-acting engines formed the power plant, with

the cylinders being on opposite sides of the ship and located at diagonally opposite corners of a rectangle circumscribing the engines, the jet of the other cylinders, the two piston rods of each cylinder striding the crank shaft. The cylinders were 72 inches in diameter by 3 feet stroke of piston and were designed to make about 45 double strokes per minute. A three-ported slide valve placed horizontally on top of the cylinder and activated by a rock-shaft was used, expansion being obtained by the use of an independent cut-off valve of the gridiron type.5

The two engines were capable of delivering a total of 869 horsepower and reaching an estimated top speed under steam power alone, in smooth water, of 8.870 knots per hour. Actually, the engines never achieved that speed. Log entries noted that under sail and steam the Merrimack reached a top speed of 10.656 knots. The frigate managed just 6 knots excessively under steam.

Steam was provided by four 4-furnace (with one auxiliary), vertical glass tube, twenty-eight-ton boilers designed by Daniel B. Martin, engineer-in-chief of the U.S. Navy. Each boiler was fourteen feet wide, twelve feet deep and fifteen feet high, with an aggregate heating surface of 12,537 square feet. The boilers each had a series of brass tubes underneath for a fired water heater; the superheated salt water was pumped through the tubes. Water was heated to 137 degrees Fahrenheit before entering the boilers. Two large steam-operated Worthington pumps were installed to keep the bilges dry or reversed to provide seawater for the boilers.6

Merrimack sail plan, circa 1855. Courtesy of the National Archives.

Merrimack’s engine, engraving, circa 1857. Courtesy of John Moran Quarstein.

All this energy only produced 869 horsepower at the propeller shaft. The engines required 103 horsepower to start, and when all this power was delivered to the segmented propeller shaft, 65 horsepower was lost from the friction of the propeller shaft turning on bearings mounted on unstable wooden supports, which dissipated even more power.

The engine system consumed a tremendous amount of space within the warship. The system had a combined weight of 129 tons and was 20.3 feet long, 22.6 feet wide and 12 feet high.

Perhaps the ship’s most notable feature was her screw propeller. This propulsion method was invented by John Ericsson, although some give credit to Sir Francis Petit Smith. The screw propeller enabled the warship’s engines to be installed beneath the waterline, thereby protecting the propulsion unit from enemy cannon fire. The Merrimack’s propeller was a two-blade bronze screw with spherical hub and blades designed by Robert Griffiths. Griffiths’s concept endeavored to enhance the engine power while also operating under sail. His concept featured a narrow blade design and fitted the propeller in its socket with an automatic pitch gear to increase the pitch as the velocity increased. When operating under steam, the propeller was set at thirty-six degrees. The blades would be set at zero and locked vertically behind the sternpost to reduce drag for operation under sail. The propeller was huge: seventeen feet, four inches in height, and it weighed fifteen tons. At full speed, the propeller would turn at forty rpm. In addition to the sternpost locking device, the Merrimack was fitted with a bronze frame hoist system called a banjo. The Merrimack’s banjo could lift the propeller out of the water completely while operating under sail; it could also allow the propeller to be raised onto the deck for maintenance.7

Despite this advanced steam-powered, screw propeller system, the Merrimack was truly designed to rely on sail power for long sea voyages. The propeller’s sternpost lock and banjo devices were major indicators of the preference for sail power. Also, the funnel was telescopic, which enabled the smokepipe to be lowered to reduce drag while operating under sail, as well as improving the frigate’s appearance when in port. The U.S. Navy and its designers appear to have added steam power as an afterthought. The hull was designed for sail, and the purpose of the steam engine was to enable the frigate to have ease moving in and out of ports while maneuvering in combat.8

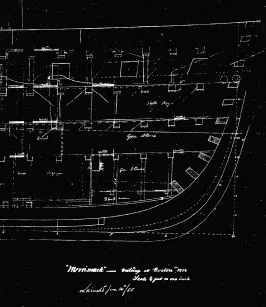

Merrimack hull plan, circa 1855. Courtesy of the National Archives.

The frigate was completed in February 1856 at a cost of $685,842.19. She was 275 feet in length with a beam of 38 feet, 6 inches and a depth of 27 feet, 6 inches. The Merrimack’s tonnage was 3,800, with a 4,000-ton capacity. The frigate’s draft was 24 feet, 3 inches. The Merrimack, based on the advice of the Delafield Report, was armed with the most advanced artillery available, making her one of the most powerful vessels afloat. Her armament was two 10-inch pivot guns, twenty-four IX-inch Dahlgrens and fourteen 11-inch guns. John Dahlgren, chief of the Bureau of Naval Ordnance, supervised the selection of the ship’s armament. All of the Merrimack’s cannons were produced at the Alger Foundry in Boston.

The USS Merrimack was commissioned on February 20, 1856, and was immediately acclaimed as the pride of the U.S. Navy. She left Boston on February 25, 1856, for her sea trials under the command of Captain Garrett J. Pendergrast. A farewell hymn was written by Phineas Stowe, pastor of the First Baptist Mariner’s Church in Boston. The hymn’s first and final stanzas proclaimed:

Saviour, o’er the restless ocean

May the gospel banner wave,

And beneath its folds of beauty

Cheer the sailor—guide the brave.

Fare-thee-well, shall be our prayer,

We on earth may meet no more;

But we’ll hope to dwell together,

On that calm and heavenly shore.

The Merrimack briefly returned to the Charlestown Navy Yard and then set sail for the Chesapeake Bay. She arrived at Annapolis on April 19, 1856, with great fanfare. President Franklin Pierce, accompanied by Secretary of the Navy James C. Dobbin, surveyed the frigate and proclaimed her “a magnificent specimen of naval architecture.”9 U.S. Naval Academy midshipmen paraded as the Merrimack’s powerful guns boomed in honor of the president and the many members of Congress who attended the gala affair.

Following the celebration in Annapolis, the Merrimack sailed to Gosport Navy Yard and then left for Havana. Her engines broke down, and the frigate made it to Cuba under sail. The Merrimack’s rudder then broke, and she was towed back to Boston. Once back in the Charlesto...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. “A Magnificent Specimen of Naval Architecture”

- 2. Flashpoint—Gosport

- 3. Iron Against Wood

- 4. The Virginia

- 5. The Race for Hampton Roads

- 6. Like a Huge Half-Submerged Crocodile

- 7. Aftermath

- 8. Enter the Monitor

- 9. “Mistress of the Roads”

- 10. Equal to Five Thousand Men

- 11. Fire a Gun to Windward

- 12. Loss and Redemption

- 13. I Fought in Hampton Roads

- Appendix I. You Say Merrimack, I Say Virginia

- Appendix II. CSS Virginia Designers

- Appendix III. The Commanders

- Appendix IV. CSS Virginia Officers’ Assignment Dates

- Appendix V. Confederate Navy Volunteers Aboard the CSS Virginia

- Appendix VI. Confederate Marines Aboard the CSS Virginia

- Appendix VII. Confederate Army Volunteers Aboard the CSS Virginia by Unit Designation

- Appendix VIII. CSS Virginia Casualties, March 8, 1862

- Appendix IX. CSS Virginia Personnel Paroled at Appomattox, Virginia, and Greensboro, North Carolina

- Appendix X. CSS Virginia Officer Assignments, March 8, 1862

- Appendix XI. CSS Virginia Dimensions and Statistics

- Appendix XII. The Crew of the CSS Virginia

- Appendix XIII. Chronology of the CSS Virginia

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The CSS Virginia by John V Quarstein in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.