![]()

Part I

KEEPERS OF THE BAY

![]()

Chapter 1

Early European Encounters

Narragansett oral history tells us that the aboriginal people of Rhode Island have existed, in Sachem Canonicus’s words, since “time out of mind.” Anthropological evidence shows that as far back as thirty thousand years ago, the tribe lived in the forests and along shoreline of southern New England, subsisting on hunting, gardening and gathering from the abundant resources available in their homeland.

At the period of their greatest authority, the Narragansett had a domain that extended throughout most of what is now Rhode Island, from Westerly in the southwest to about Pawtucket and the Blackstone River valley in the northeast, and also included Block Island offshore and Conanicut Island in Narragansett Bay.

Narragansett sachems ruled extensive territories by their authority respected beyond traditional homelands, holding considerable influence over the Nipmuck, Pokanoket, eastern Niantic and other remaining tribes of the area. At the peak of this authority, the tribe’s population was reputed to be as high as thirty-five to forty thousand.

In communities throughout southern New England, these Native Americans predominately grew corn, beans and squash though also hunted deer, beaver, fowl and sea birds, as well as fished and harvested clams and oysters from the bay. Early tools were made from shells or soapstone that had been quarried from stone outcroppings on their lands, including sites identified in Oaklawn and Neutaconcanut Hill. The Narragansett also obtained wealth from the shores in the way of “Wampompeage,” or wampum, as it came to be known to Europeans, harvesting the unlimited resources of shells from the bay and fashioning the pearl-like interiors of whelks and the purple shells of the quahog into a currency that was used up and down the eastern seaboard. William Wood wrote in an early description that the Narragansett were “Mint-masters,” so skilled in their manufacturing that English attempts at producing counterfeit currency were dismal failures.

The origins of the Narragansett people have been debated for at least three centuries; however, William Simmons related the earliest known reference from oral history to a “great sachem” named Tashtasick. It was the eldest grandson of this sachem, known as Canonicus, who would befriend Roger Williams during the period in which the tribe is most recorded.

Narragansett members called the first Europeans they encountered “Chauquaquock,” or “knife-men,” and were quick to recognize the advantages of trading for the iron axes, knives and hoes that these visitors brought to their shores. Despite the initial eagerness to deal with the newcomers, there is no doubt that the English who would eventually colonize the Narragansett country interrupted a successful way of life that had formed over many generations.

The first European record of the tribe came from the visit of Giovanni da Verrazzano, who spent fifteen days with the Narragansett during his journey up the Atlantic seaboard in 1524. His letter to Francis I contained an early description of Narragansett Bay:

The coast of this land runs from west to east. The harbor mouth faces south, and is half a league wide; from its entrance it extends for XII leagues in a northeasterly direction, and then widens out to form a large bay of about XX leagues in circumference. In this bay there are five small islands, very fertile and beautiful, full of tall spreading trees…Then, going southward to the entrance of the harbor, there are very pleasant hills on either side, with many streams of clear water flowing from the high land into the sea.

The Narragansett welcomed the visitors, as was their custom, boarding their ships bearing gifts and leading them back to their homes for feasting and entertainment. Tribal history records that the explorer was greeted by Tashtasick and by Canonicus, who was then a young man.1 Verrazzano described the tribe as “the most beautiful and have the most civil customs that we have found on this voyage.” He was much taken by their appearance, describing the men as “taller than we are; they are a bronze color, some tending more towards whiteness, others to a tawny color. The face is clear-cut, the hair is long and black, and they take great pains to decorate it; the eyes are black and alert, and their manner is sweet and gentle.”

He was also much taken by the appearance and manners of the women, writing that

[t]heir women are just as shapely and beautiful; very gracious, of attractive manner and pleasant appearance…they go nude except for a stag skin embroidered like the men’s, and some wear rich lynx skins on their arms; their bare heads are decorated with various ornaments made of braids of their own hair which hang down over their breasts on either side.

While writing of their generosity and hospitality, he did note, however, that they held extreme caution with regard to their “womenfolk”: “They are very careful with them, for when they come aboard and stay a long time, they make the women wait in the boats; and however many entreaties we made or offers of gifts, we could not persuade them to let the women come on board ship.”

It is perhaps telling in this fact that the Narragansett so carefully guarded their women. Verrazzano was likely not the first European encountered, nor the first to admire native women, and earlier encounters with trappers and traders from France, England and Canada, as well as Dutch fishermen, may have resulted in interracial relations, normally frowned on by Native Americans at this time,2 who saw their bloodlines as something that should be pure and protected. Nonetheless, the prospect of trade and commerce enjoined the Narragansett, like other tribes surrounding them, to continue to welcome Europeans and the goods brought with them.

Around 1570, however, less than fifty years after Verrazzano’s visit, a devastating illness took what was estimated by the tribe’s preservation officer to be 80 percent of the population of the Narragansett at that time. It was a forewarning of plagues to come, and as tribes along the East Coast of America suffered these afflictions, the white visitors took full advantage of the devastation. Another early visitor to Narragansett shores was the Dutch trader Adrian Block, who skirted the island that would later bear his name and slipped into Narragansett Bay to locate the tribe that he called the Nahican; the Dutch were already familiar enough with the area to distinguish between the Narragansett, whom he found on the western side of the bay, with the Wamponec, or Wampanoag, the neighboring tribe.

By the early seventeenth century, the Narragansett still remained somewhat isolated from European settlement. Canonicus’s famous “gift” of arrows in a snakeskin given to the Pilgrims at Plymouth signaled an early resistance to any white intentions of settling on Narragansett lands. This proved to be of considerable fortune when the first epidemic of smallpox swept through New England beginning in 1629. By 1634, Narragansett people had lost up to seven hundred of this generation of the tribe, but this was a small loss compared to the desolation wreaked by the outbreak on neighboring tribes in New England.3

These encounters indicate that at the time of Roger Williams’s fabled landing on their shores, the Narragansett were as familiar with white visitors as Williams was with the native language. The circumstances of his stepping ashore from the wide cove at the eastern edge of what would become the settlement of Providence preceded an unprecedented period of political turmoil for the Narragansett. In time, it would matter little that Williams proved to be a friend and defendant of their rights. Their acceptance of the white visitors exiled from Massachusetts was the beginning of an encroachment that would bring the tribe to the edge of extinction.

Williams had entered the wilderness of New England as a trader and a missionary, learning the language of the Algonquian tongue by listening and taking meticulous notes. In time, Williams came to a singular understanding of the Narragansett exceeding any prior Jesuit, Puritan-oriented minister or, perhaps, white visitor to the tribe. It was his view as a separatist and his long-growing idea of “liberty of conscience” that allowed him to glimpse the nobility of Narragansett life and portray that life with an undiminished admiration for its virtues.

Much has been written and mythologized concerning Williams’s banishment and his arrival on the shores of Rhode Island. This mythology comes partly from Williams’s own writings, which were published years after the events. Having been sentenced to banishment on October 19, 1634, he almost immediately fell ill and, after recovering, delayed his exile until January 1635, when he received word from Governor Winthrop that a group of magistrates was en route to arrest him and expedite his return to England. According to Williams’s own account, Winthrop advised him explicitly to “go into the fertile, comely, and as yet unsettled Narragansett country.” Williams’s description of his flight as “[e]xposed to the mercy of an howling wilderness in frost and snow…sorely lost for…fourteen weeks, in a bitter winter season, not knowing what bed or bread did meane” is somewhat misleading.

The Roger Williams Monument in Providence, Rhode Island. Photo by author.

From Henry Martyn Dexter’s early, meticulous research, we know that Williams entered exile not alone but rather with four companions, two of the men being John Smythe, a miller from Dorchester, and William Harris, who would write his own pamphlets on religion once in the safe haven of “New Providence.” Moreover, as Williams lay recovering from illness with the certainty of exile looming, “some of his friends went to the place appointed before hand, to make provision of housing, and other necessaries for him against his coming.”4 This reportedly included at least three more men and eight women, all of whom were undoubtedly dispatched to the land that Williams had purchased years before from Ousamaquin to begin a new colony. According to Dexter, Williams “most likely…went as quickly as he could to Sowams [Warren, Rhode Island] the home of his friend Massasoit (Ousamaquin).”5

We know, as mentioned before, that Williams was already acquainted with the neighboring Wampanoag, Niantic and other smaller tribes and that while in Plymouth he had written a “treatise” that had caused some consternation among officials, namely Plymouth governor Bradford, who was already wary of Williams’s “strang opinions.” The treatise was brought to the attention of the authorities, and in December 1633, a meeting was held to pass judgment on the document. The panel included Massachusetts Bay Colony governor John Winthrop, whose journal recorded that “wherin, among other things, he disputed their right to the lands they possessed here, and concluded that, claiming by the King’s Grant, they could have no title, nor otherwise, except they compounded with the Natives.”

More to the panel’s displeasure, however, than this signature claim of Native American rights were the slanders against the English King Charles II. Unfortunately for historians, any copies of the “treatise” printed have disappeared.

By the autumn of 1636, Williams and a handful of his followers had spent nearly a year in exile, enduring “the miserie of a winter’s banishment among the barbarians,” those tribes that lived outside the shaky boundaries of European control. Williams and his followers walked southeast from Salem, camping out in the smoky longhouses, accepting Indian hospitality, until they reached the bank of the Seekonk River, where the crude housing constructed there was surely little better than the native houses they had shared.

Here Williams found himself and the others in a precarious position between those who had banished him and those on whom he depended for survival.6

Informed some weeks later that this land was also within the Massachusetts Bay Colony domain, Williams was directed downriver to the Eastern Shore, where a curious group of natives gathered to greet the long dugout canoe he had borrowed for the short journey. It was, he wrote years later, “a shaggy world of primeval forests, red men, and freedom.”

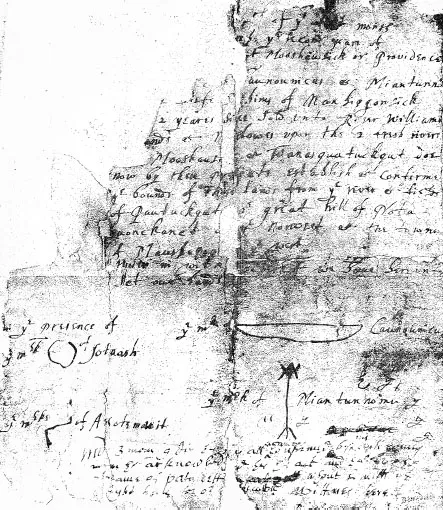

The original deed signed by Canonicus and Miantonomo with Roger Williams for the purchase of Providence. Courtesy of the Providence City Archives and the State of Rhode Island.

Once led to what would become Providence Plantations, Williams and his group flourished in remarkable time, establishing a trading post in Cocumscussoc near Wickford and a community in Providence at the meeting of the Moshassuck and Woonasquatucket Rivers, which brought trade with natives from Seekonk, Rehoboth and beyond. Williams became friends with Canonicus, the sachem who had been among those who greeted him ashore, as well as his nephew, Miantonomo, another leader whose later stance against European encroachment would leave a legacy as a precursor of the Wampanoag Philip (Metacom) in native resistance.

Seven years after stepping ashore onto Narragansett lands, Williams was en route to England to obtain the charter for the lands had had acquired with others from the Narragansett. He took the weeks of ocean voyage to compose a remarkable book on the language and culture he had shared in the past seven years. Ostensibly a guide for missionaries “to spread civility and Christianity; for one candle will light ten thousand,” his pamphlet A Key into the Language of America was unique in its compilation of the Algonquian language, far exceeding any contribution before, and notable as well for Williams’s “briefe Observations of the Customs, Manners and Worships Etc. of the aforesaid Natives, in Peace and Warre, in Life and Death.”

Less than a decade after his “banishment among the barbarians,” Williams wrote of the natives, “I have acknowledged amongst them an heart of sensible kindnesses, and have reaped kindness against from many, seven years after, when my selfe had forgotten.”

In his inimitable style, Williams scoffed at those Europeans who thought the natives uncivilized: “The sociablenesse of the nature of man appears in the wildest of them, who love societie, families, cohabitation, and consociation of houses and townes together…There are no beggars amongst them, no fatherless children unprovided for…their affections, especially to their children are very strong.”

This sociableness extended to an equal contribution to the subsistence of the tribe as a whole:

When a field is to be broken up, they have a very loving sociable speedy way to dispatch it: All the neighbors men and Women forty, fifty, a hundred &c, joyne and come in to help freely.

With friendly joining they breake up their fields, build their forts, hunt the Woods, stop and kill fish in the Rivers, it being true with them as in all the World in the Affaires of Earth or Heaven.

Williams found an intelligent and curious people who had grasped a clear understanding of what many Europeans saw as a vast and frightening wilderness. “It is a mercy,” he wrote, “that for a hire a man sh...