This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lincoln's Springfield Neighborhood

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

When an emotional Abraham Lincoln took leave of his Springfield neighbors, never to return, his moving tribute to the town and its people reflected their profound influence on the newly elected president. His old neighborhood still stands today as a National Historic Site. The story of the life Lincoln and his family built there returns to us through the careful work of authors Bonnie E. Paull and Richard E. Hart. Journey back in time and meet this diverse but harmonious community as it participated in the business of everyday living while gradually playing a larger role on the national stage.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Lincoln's Springfield Neighborhood by Bonnie E Paull, Richard E. Hart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

LINCOLN’S SPRINGFIELD

The Beginning of the Town

I now felt firmly rooted, and determined to seek no further, as I believed I was then in the center of the most extensive body of the richest land in the United States, or perhaps in the world; and don’t yet think I was mistaken.1

—Elijah Iles

Nine years before Thomas Lincoln and his family migrated north from Indiana to Macon County, Illinois, Elijah Iles, a twenty-five-year-old pioneer, arrived on horseback in what is now Springfield. In 1821, only nine settlers populated this area of maple, hickory and elm groves surrounded by thousands of acres of prairie. Among them was John Kelly—the first man to build a cabin in Springfield on what are now Jefferson and Second Streets.

An enterprising adventurer, Iles left his Kentucky home for St. Louis. He remained there for three years, learning to trade, to keep shop and to buy and sell land. Still restless and in search of his ideal home, he traveled from Missouri through the waving grass of the prairie to the rich land of the Sangamo Country in central Illinois. Iles, being the visionary that he was, saw its potential and decided to settle down here permanently. He boarded with the Kelly family while he established the first store in this tiny wilderness settlement. He eventually came to be known as the “Father of Springfield.”

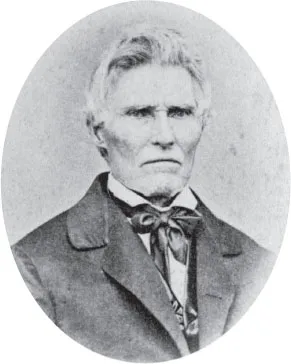

Elijah Iles, one of Springfield’s founders and the developer of the Lincoln Home neighborhood, pictured in a photograph by Christopher Smith German of Springfield, Illinois. From the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, courtesy of the Allen County Public Library and Indiana State Museum.

I was the first one to sell goods in Springfield. For some time my sales were about as much to Indians as to the whites. For the first two years I had no competition, and my customers were widely and thinly scattered over the territory… Many had to come more than eighty miles to trade. They were poor, and their purchases very light. There never was a more uniformly hospitable, honest, and industrious class of first settlers [who] ever settled new country.2

In 1823, the federal land office opened at Springfield, then a small village of twenty or thirty log cabins stretched along Jefferson from First to Fourth Streets. When parcels of land were offered for sale, Elijah Iles and three of his friends—Pascal P. Enos, Thomas Cox and John Taylor—purchased four adjoining parcels for $1.25 an acre and had them surveyed into lots that became the original Town of Springfield. They then proceeded to sell the lots.3

They named the town’s first streets for American presidents—Monroe, Adams, Washington, Jefferson and Madison—and the village itself “Calhoun” after the popular South Carolina senator John C. Calhoun. When the little village was legally incorporated in 1832, the name was changed to that of a nearby creek, a name preferred by the residents: Springfield.

In 1824, Springfield was selected as the permanent county seat of Sangamon County. The census recorded just five hundred residents. By now, many transients had left for “less populous” areas where they could not see the smoke from a neighbor’s home; it was in this same year that Iles built his first home from logs.

Springfield Becomes the Capital

By 1837, thanks to the efforts of Lincoln and “the Long Nine,” a group of legislators all over six feet tall, the state capital was moved from Vandalia to Springfield, closer to the geographic center of the state. This move, which was completed by 1839, would alter forever the history of this frontier village now grown to two thousand inhabitants.

Naturally, a state capital demanded an appropriate building, so the county courthouse on the public square was demolished, making way for the new capitol, and a new courthouse was erected on the east side of Sixth Street.

Iles continued promoting the rich agricultural potential of the area, but it was his town real estate ventures that made him a millionaire. Shrewdly anticipating the town’s growth as the new capital, he began the construction, in 1836, of Springfield’s first luxury hotel at the southeast corner of Sixth and Adams Streets, and the American House opened its doors in 1838.

The Illinois State House during Lincoln’s time in Springfield. This photograph was taken by an unknown photographer from a building on Fifth Street looking east. Courtesy of the Sangamon Valley Collection, Lincoln Library, Springfield, Illinois.

A visiting Ohio editor remarked somewhat sarcastically of Iles’s hotel that “everything inside puts you in mind of the Turkish splendor: the carpeting, the papering and the furniture, weary the eye with magnificence.”4 Its popularity was instant. In one week alone in 1839, when the legislature was in session, 158 people registered at the grand American House. Many of them were legislators who lived too far away for frequent visits home.

With his typical foresight and energy, while the American House was still under construction, Iles began the first of several housing additions (now called subdivisions) that came to bear his name. One contained 436 lots and covered a twenty-seven-block radius. It was here that the now famous Lincoln Home was built in 1839 and also Iles’s own second home.

Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln Arrive in Springfield

In 1837, Mary Todd made her second visit to Springfield as a guest of her eldest sister, Elizabeth, wife of Ninian Wirt Edwards, son of Ninian Edwards Sr., first territorial governor of Illinois. In this same year, Lincoln was admitted to the bar and rode with two saddle bags, his borrowed horse and seven dollars in his pocket from New Salem to Springfield. Now a bona fide lawyer, he planned on launching his first law practice with Mary’s cousin, John Todd Stuart.

This was also a year of other notable events. Eighteen-year-old Victoria became Queen of England and reigned for the next sixty-three years; Chicago incorporated as a city; the electrical telegraph, which later became a great help to Lincoln, was patented; and a financial panic hit, the worst since the country’s founding, creating a major recession. Unemployment soared, banks collapsed and many businesses failed.

Despite the country’s financial plunge, Mary and Abraham were young and hopeful about the future. But they were disappointed in Springfield. It was nothing like the sophisticated Lexington, Kentucky—the “Athens of the South”—where Mary was born and brought up. Lincoln wrote to Mary Owens, whom he had courted in New Salem, that he found the town “a busy wilderness.”5

Earlier in the decade, the poet William Cullen Bryant, passing through Springfield, had departed with a negative impression: “The houses are not so good…a considerable portion of them being log cabins and the whole town having an appearance of dirt and discomfort.”6

Mary Lincoln pictured in a circa 1846 daguerreotype (photograph) by Nicholas H. Shepherd of Springfield, Illinois. This is the earliest confirmed photographic image of Mary Lincoln. Courtesy of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum. The original is in the Library of Congress.

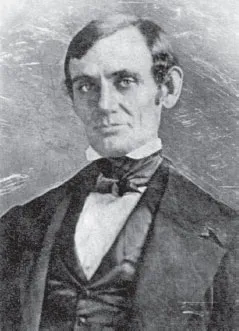

Abraham Lincoln pictured in a circa 1846 daguerreotype (photograph) by Nicholas H. Shepherd of Springfield, Illinois. This is the earliest confirmed photographic image of Abraham Lincoln. Courtesy of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum. The original is in the Library of Congress.

In the absence of sidewalks and paved streets, the pig population wandered freely through the often muddy streets. While pro-hog and anti-hog factions argued, the porcine population continued to enjoy its freedom, rooting in the dirt and wallowing in the mud. Chickens and dogs sometimes joined in the fun. And in wet or wintry weather, carriages routinely got stuck in the dark sludge of the roadways.

Meanwhile, Simeon Francis, editor of the Sangamo Journal and the man who was to bring together Mary and Abraham after their romantic breakup, was optimistic, enthusiastically promoting the exciting growth of the new capital:

The owner of real estate sees his property rapidly enhancing in value; the merchant anticipates a large accession to our population and a corresponding additional sale for his goods; the mechanic already has more contracts offered him for building and improvement than he can execute; the farmer anticipates, in the growth of a large and important town, a market for the varied products of his farm; indeed every class of our citizens look to the future with confidence that we trust, will not be disappointed.7

From the small square at Second and Jefferson where Iles’s store and the first courthouse had stood, Springfield’s new town center expanded its boundaries. The State House moved toward completion. Assisting was brick mason Jared Irwin, later a neighbor of the Lincolns and one of many workmen lured from the East by job opportunities in Springfield. One- to three-story buildings were constructed on Fifth Street south from the corner of Washington, as well as along Hoffman’s Row, where Lincoln shared an upstairs office with John Todd Stuart. Craftsmen’s signs in growing numbers invited customers to purchase hats, shoes, leather goods and clothing.

Further, the administration of state government and the growing community required more service providers: clerks, doctors, lawyers, mechanics, hoteliers, builders and shopkeepers. Even a bookstore appeared, a sure sign that culture was coming to the prairie.

Robert Irwin opened a general store where Lincoln’s close friend Joshua Speed had once done business and where Lincoln had made his first home in the community. Irwin’s welcomed frequent customers like Mary Todd—a serious shopper who delighted in choosing from among the variety now available of lovely fabrics, ribbons, straw hats, coffee and tea.

At the same time, Springfield was becoming a town of politically aware and involved citizens. On every street corner, in shops on the square and in new drinking establishments, lively political discussions took place. During presidential campaigns, tempers ran high. In 1839, during the election campaign of William Henry Harrison and Martin Van Buren, both the Whigs and the Democrats arrived by the thousands to hold their state conventions in the new capital. Speaking tournaments went on for hours followed by torchlight parades, singing and barbecues until midnight.

Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln flourished in this milieu. “This fall,” she wrote, “I became quite a politician, rather an unladylike profession, yet at such a crisis, whose heart could remain untouched while the energies of all were called in question?”8

And people partied! When in session, the legislature included many eligible bachelors. This meant a lively social life attracting marriageable young women like Mary Todd and her sisters. The home of her sister Elizabeth and brother-in-law Ninian Wirt Edwards was a popular venue for many entertaining gatherings of what Mary called the “the coterie,” including awkward Abraham Lincoln, his friend Joshua Speed and the brilliant young politician Stephen A. Douglas. Isaac Arnold, a legislator, remembering Springfield of those early capital days, said, “We read much of ‘Merrie England,’ but I doubt if there was ever anything more ‘merrie’ than Springfield in those days.”9

The Lincolns Buy a Home

As the city grew, so did the churches and their need for bigger and better buildings and new ministers. The local Episcopal Church, seeking a new pastor, contacted Reverend Charles Dresser of Virginia. He accepted the position and moved with his wife, Louisa, and two sons to Springfield in 1838. The following year, he decided to build a home and purchased Lot 8 in Block 10 of the Elijah Iles’s Addition (subdivision). The lot Dresser purchased had been owned originally by Elijah Iles. It was bought by Dr. Gershom Jayne, Springfield’s first physician, who then sold it to the Dressers. In order to accommodate the building plans, Dresser paid ninety dollars to Francis and Emeline M. Wester Jr. for an additional ten-foot-wide strip off the south side of the lot.10

The home Dresser built faced Eighth Street and was a modest cottage of one and a half stories that extended 150 feet north, down Jackson Street. It stood on a rise above the unpaved street. Shutters flanked the set of two windows on each side of the walnut front door.

On the ground floor, the home contained a parlor, a sitting room with fireplaces for heating and a kitchen. Above, in the half loft, there were two low-ceilinged bedrooms under the slanting roof. Reverend Dresser added an outhouse and possibly a barn in the back, along with a well and cistern for collecting rainwater.

By November 4, 1842, Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln had passed through their stormy courtship and engaged Reverend Dresser to perform their marriage ceremony in her sister’s parlor. At this time, Reverend Dresser had his own problems. He was struggling with debts and eager to sell his Eighth and Jackson property. Lincoln would most certainly have visited the home and probably found it to his liking, but the time was not right for him to make this kind of financial commitm...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword, by Dr. Wayne C. Temple

- Preface, by Bonnie E. Paull

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction, by Richard E. Hart

- Lincoln’s Farewell Address

- 1. Lincoln’s Springfield

- 2. Mary Todd Lincoln and Her Neighbors

- 3. Lincoln, His Boys and the Neighborhood Children

- 4. A Neighborhood of Diversity—Foreign Born

- 5. A Neighborhood of Diversity—African Americans

- 6. The Schools in and Near the Lincoln Neighborhood

- 7. Political Allies and Opponents in the Neighborhood

- 8. Parties and Parades in the Neighborhood

- Appendix A. Irish Families Living in the Lincoln Neighborhood

- Appendix B. Irish Servants Living in the Lincoln Neighborhood

- Appendix C. German Families Living in the Lincoln Neighborhood

- Appendix D. German Servants Living in the Lincoln Neighborhood

- Appendix E. English and Scottish Families Living in the Lincoln Neighborhood

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Authors