![]()

Chapter 1

THE BEGINNING

Bars, Brothels and Bad Neighborhoods

It’s been known as many things: the Capital of the New South, the Gateway City, the City Too Busy to Hate. A place where business booms and growth is a given. A cradle of gentility, hospitality and soft melodious accents. Atlanta is all of these things.

But it didn’t start out that way. In its infancy, Atlanta was a rough-edged frontier town, a Wild West settlement in the heart of the Deep South, known for bars, bordellos and unrestrained lawlessness.

A RAILROAD TOWN ON THE GEORGIA FRONTIER

If Atlanta’s birth date were to be named, it would be the day in 1837 when, in the heart of present-day downtown, a stake was driven into the red Georgia clay, marking the spot of the future railroad hub of the South.

Prior to that fateful day, Atlanta was just a sparsely populated settlement of about thirty-five families, approximately 253 people in total scattered from present-day Grant Park to Buckhead. It was a span of thirteen miles—a long way to go to visit a neighbor, especially by horse-drawn carriage. Far from being on its way to becoming a major city, Atlanta wasn’t even headed in the direction of becoming a village. Then came the day that changed everything.

It happened like this: State legislators had started to notice that Georgia was missing out on lucrative trade opportunities to the west. The reason wasn’t hard to figure out: there was simply no way to get there. Georgia needed a westbound railroad, and the legislature voted to build one.

The plan was to create a railroad from Georgia to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Two existing railroads, one between Macon and Savannah and the other between Athens and Augusta, would be extended to the new line’s endpoint in Georgia.

The question was: where should the endpoint be? To find the optimal site, surveyors were deployed to determine the location. Their quest ended in northern Georgia, just southeast of the Chattahoochee River. They drove a stake into the ground and changed the destiny of that barely settled area forever.

Eager settlers rushed to the promise that a railroad town held, and not just any railroad town, but one that would link a network of rails heading in all four directions. The lure was too much to resist.

A flow of railway workers, fortune hunters, gold prospectors, land speculators and enterprising pioneers poured in. More than three hundred of them were Irish, who mainly came looking for railroad work. The Irish alone more than doubled the population.

It was hot, isolated and not for the faint of heart. After all, it was a frontier town, with all that that implies. Saloons and brothels sprang up quickly, and the settlement soon gained an unsavory reputation as a place of debauchery, where liquor flowed and “painted ladies” strolled the streets. The typical hallmarks of a growing community—schools, residential neighborhoods, places of worship—took awhile to take root, at least in any significant number. Indeed, the first tavern opened for business ten years before the first church was built.

As growth continued, the seedier elements became centralized in three areas, all close to today’s downtown. Murrell’s Row was a favorite hangout for thieves, gamblers and prostitutes. It was named for John Murrell, a notorious bandit who ran a thievery network rumored to include hundreds of participants with outposts in Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi and Georgia. Whether Murrell ever got as far east as Georgia is unknown, but the name “Murrell’s Row” is unquestionably a reference to the lawlessness of the area. Murrell’s Row started at the intersection of Line, Decatur and Peachtree Streets, today’s Five Points, and progressed eastward toward Pryor Street.

Slabtown was the second of the blighted areas. Built largely with abandoned concrete slabs used for construction, it was a red-light district located where Grady Memorial Hospital now stands. Third in the triumvirate was Snake Nation, so named due to the large number of snake oil salesman and the generally bad characters who called it home.

“Nothing serves as a reminder that Atlanta was once a frontier town more than the history of its early shanty town settlements in the late 1840s and 1850s,” writes author Vivian Price in The History of Dekalb County, Georgia, 1822–1900. Snake Nation, she says, “was devoted almost entirely to the criminal and immoral element. Snake Nation, Murrell’s Row and Slabtown were pockets where drinking, gambling and brothels were common, and murders were not uncommon.”

Arrests were practically pointless because the small wooden jail, measuring only twelve square feet on the outside and eight on the inside, was not sturdy enough to keep anyone locked up for long. About two criminals per day were brought there, and they could easily dig their way out. When there were enough of them, they just flipped the flimsy structure over. Once, when a big uproar had filled the prison, friends of the incarcerated arrived in the middle of the night, lifted the building off its foundation and held it up while the jailed men emerged from underneath.

Noted Atlanta historian Franklin Garrett describes the situation: “By 1851, law and order in Atlanta had come perilously close to extinction. The authority of the municipal government was being openly flouted by ‘toughs’ from Murrell’s Row and Snake Nation.”

THE REIGN OF THE ROWDIES

It all came to a head in the mayoral election of 1850, a bitterly fought political battle between the two parties that had always divided the town: the Free and Rowdy Party and the Moral Party. Needless to say, they had very different outlooks.

Consisting mainly of the Irish, the Rowdies had run the show in Atlanta since its founding, many owning saloons, distilleries and brothels. The first three mayors—Moses Formwalt, Benjamin Bomar and Willis Buell—were all Rowdies.

The first election took place in January 1848. The Rowdy candidate, Moses Formwalt, was the owner of a tin shop on Decatur Street, where he made and sold liquor stills. Only twenty-eight when he ran for office, Formwalt garnered the majority of the 215 votes cast, but victory did not come easily. Election day was fraught with violence, and approximately sixty fights broke out before it was over.

Grave site of Moses Formwalt, Atlanta’s first mayor. Formwalt’s body was moved to this location in Oakland Cemetery, and the monument was erected in 1848. Author’s Collection.

Violence continued to run through Formwalt’s life. After completing his one-year term as mayor, he became deputy sheriff of Dekalb County. Two years later, while Formwalt escorted a prisoner from council chambers, he was stabbed to death with a jagged knife. He was originally buried in an unmarked grave in Oakland Cemetery, but in 1907, the city council decided to build a memorial more suitable for Atlanta’s first mayor, and Formwalt’s casket was exhumed and moved to a more prominent place in the cemetery.

In direct opposition to the Free and Rowdies, the Moral Party promoted temperance, chastity and a government of law and order. Temperance and chastity were clearly not in the business interests of the Rowdies: their governing approach was more a containment of chaos, through force if necessary. But in 1850, the Rowdies’ rule was about to come to an end. A successful businessman was running for mayor as the candidate for the Moral Party. Things were about to change.

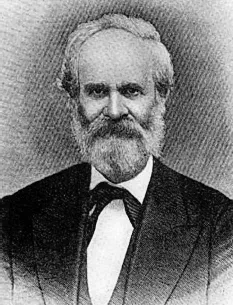

Jonathan Norcross was a man with roots that ran deep in American soil. A descendant of one of the original pilgrims to come from England and settle in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Norcross had Puritan blood in his veins and a strong work ethic in his soul. He arrived in Atlanta in 1844 and quickly established a thriving dry goods business and sawmill operation. Interestingly, the discarded timbers from the Norcross Mill were used to build the shanties of Slabtown.

In 1848, Norcross entered politics and ran in Atlanta’s first mayoral election. But it was still Rowdy time then, and Norcross came out the loser. Two years later, he tried again. This time, the outcome was different, but only after heated and divisive campaigning. Norcross, the candidate representing clean living and civil obedience, was up against Rowdy Leonard Simpson, whose followers owned the town’s forty-plus bars and thriving brothels. Their election tactics underscored their differences: while Norcross handed out apples and sweets, Simpson gave away whiskey. In the end, temperance and candy prevailed, and the Moral Party took the election.

Jonathan Norcross, the first Moral Party candidate to be elected mayor. Creative Commons.

With or without a majority, the Rowdies weren’t about to turn the reins over without a fight. At the time, whoever was mayor was also the superintendent of the streets and the chief of police. In those capacities, he presided over the trials of municipal law violators. This was no small part of the job because Atlanta, although it had an increasing number of law-abiding citizens, was still a town of rough edges.

It didn’t take long for the first violator to appear in police court. No more than two days into Norcross’s term, a burly offender was brought before him for creating a disturbance in the streets. His offense was most likely just a contrivance to cause trouble for the new mayor. Suspicions arose that a whole group of Murrell’s Row ruffians planned to follow this up by getting themselves arrested as well. That way, they could attack the mayor in the courtroom when the first man was brought to trial.

Despite concern over possible violence, the matter proceeded without incident. Norcross found the man guilty, imposed a fine and moved on to the next case. But before he could begin, the convicted man leapt to his feet, brandishing a knife with a long blade of polished steel. Threatening to “chop into bits” anyone who came near him, he began slashing the air in all directions, as if to prove that he meant what he said.

The case had attracted a crowd of spectators, primarily Rowdies, curious to see how the new mayor would handle the trial of their man. But when the knife slashing began, panic and personal safety overrode curiosity and support, and the onlookers clamored to get out, pushing their way down the narrow stairway and out the door. A few men, however, stood their ground. Norcross was one of them. Calmly, he rose from his seat, turned around and picked up his chair to use to defend himself.

Sheriff Allen Johnson had also remained in the courtroom, and the moment he saw his chance, he lunged at the armed man. Johnson hit the convict’s hand that held the knife and sent the shining silver weapon clattering to the floor. Instantly, Johnson and clerk of the court C.H. Strong grabbed the now unarmed Rowdy and pushed him down the stairs and out into the street, where he ran away in fear. Norcross and the new Moral regime had prevailed.

But the Rowdies hadn’t given up quite yet. A few days later, they managed to come up with a cannon used for Fourth of July celebrations. They mounted it on wheels and hauled it along the dirt roads until they reached Norcross’s dry goods store. There, they parked the cannon, which they had packed with dirt and leaves, and fired directly at the store. The action was a threat—a promise to do serious damage if Norcross didn’t pack up and leave town. They figured the cannon blast should do it.

They were wrong. Norcross not only didn’t do what they’d expected, but he also did the opposite. Instead of fleeing, he reached out to the citizens who supported him and rapidly organized them into a volunteer militia. The Morals believed in law and order, and if the Rowdies thought that meant quietly following the rules no matter what the circumstances, they were mistaken. If it took an armed attack to defend the peace and civil obedience of their town, that’s what the Morals would do.

They moved in on Decatur Street, where Rowdies had also assembled. It didn’t take long for the organized militia to overtake the disordered Rowdies. Most were more bluff than brawn and soon turned tail and ran. Only fifteen or twenty remained but were easy arrests for the one-hundred-plus citizen army. They were taken to the small wooden jail, and because it couldn’t hold all of them, only the leaders were locked up. They were guarded throughout the night and taken before the mayor the next day. He gave them the maximum fine allowed and let them go on their way.

From then on, the Rowdies presented little disruption to the peaceful operation of the city. Norcross’s show of strength and fast planning had moved Atlanta forward, from rough frontier town to one on its way to bigger and better things.

THE TIGHT SQUEEZE

That said, the city still had problems with crime, especially in hard economic times. With the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865, Atlanta found itself in a classic postwar situation, trying to get back to normal despite the feeling of desperation that filled the streets. The hungry, homeless and wounded were everywhere, and money was scarce.

The main north–south artery was Peachtree Road, which started at downtown’s Five Points and followed an old Indian trail north to the small settlement of Buckhead. In the years following the Civil War, residential Atlanta extended only a short distance along Peachtree, no farther than Second Street. Peachtree continued on until its path was interrupted by Eighth Street—and a large thirty-foot ravine. To avoid it, the road sharply angled to the west. It proceeded along what is now Crescent Avenue until reaching the area between Eleventh and Twelfth Streets, where it returned to its original course.

The loop around the ravine was narrow, crooked and lined with heavy woods. Populated by thieves and cutthroats, it became known as the “Tight Squeeze” because it was said that it took a tight squeeze to get through there with your life. Anyone forced to travel along the twisting road through the forest faced a dangerous trip.

Just north of the ravine, where Peachtree crossed Fourteenth Street, there was a wagon yard where sellers from the north unloaded their freight for downtown merchants to pick up. The merchants were prime targets in the Tight Squeeze, either as they headed north with pockets full of cash to pay for the goods they were going to collect or upon their return with wagons full of new merchandise.

Two attacks in particular pushed Atlantans to the breaking point. On February 22, 1867, Confederate veteran John Plaster was hauling a load of firewood by ox cart into the city. After dropping it off, he headed back home. He never made it past the Tight Squeeze. Plaster, who was the grandson of one of Atlanta’s original pioneers, Benjamin Plaster, received a brutal blow to the head before he made it to Eleventh Street. He was found lying in the middle of the road, his ox team standing silently to the side. Still alive, he was carried to a nearby house but died soon after.

Around the same time, another respected citizen, Jerome Cheshire, was attacked. Unlike Plaster, Cheshire survived, but his injuries were so severe that he lived with the resulting pain for the remainder of his life. The two attacks, so close in time and both carried out on well-regarded members of the community, resulted in a grand jury call for action:

The recent frequent atrocious attempts at murder and robbery upon respectable persons returning from the City of Atlanta after the transacting of their ordinary business, admonishes that something should be speedily done to arrest such terribly outrageous conduct. We cannot too heartily commend the action of the Mayor and the city council of Atlanta, as well as the citizens, for the liberal rewards offered for the apprehension of the perpetrators of the villainous deeds already committed. But this is not sufficient. The prevention of future similar occurrences must be provided for at once. We therefore recommend the Inferior Court and the Mayor unite in raising a force of secret detectives sufficient to patrol constantly the avenues leading to the city; adopt a prudent and judicious plan of operations; appoint men sober, steady, and energetic, and we sincerely believe that if this course is faithfully carried out, the present alarming state of affairs will soon be changed to one of quiet and security.

(Minutes of the Supreme Court, Fulton County, 1867, Book E)

After this and continuing throughout the 1890s, the Tight Squeeze became something of an urban renewal project. By the 1870s, while the city’s border was still located around Sixth Street, residential “suburbs” had continued to develop and progress farther north along Peachtree. Land speculators wanting to sell homes in the Tight Squeeze zone optimistically began calling it “Blooming Hill” and pitched hard to change the circle of land’s negative reputation. A few years later, the men of the Gentle...