eBook - ePub

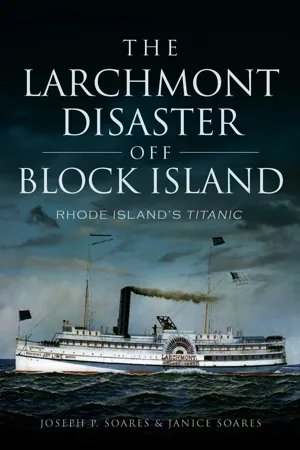

The Larchmont Disaster Off Block Island

Rhode Island's Titanic

This is a test

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

On February 11, 1907, the steamship Larchmont collided with the schooner Harry Knowlton. Thrown from their bunks, passengers of the Larchmont panicked and ran onto the ship's deck. Haphazardly loaded lifeboats set out only partially full, and shrieks from those left behind were heard in the distance. Nearly 150 passengers were lost that night. The men and women of Block Island courageously aided those in need and dealt with the horrors that washed ashore. Controversy swirled around the conduct of the captain and crew of the Larchmont as investigators tried to determine who was responsible for the collision. Authors Joseph and Janice Soares chronicle one of the greatest disasters in New England's waters.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Larchmont Disaster Off Block Island by Joseph P Soares, Janice Soares in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

NIGHT OF TERROR

A strong northwesterly wind blew down through the eastern passage of Narragansett Bay on the night of February 11, 1907. The passenger steamer Larchmont, loaded with passengers and freight, left the wharf at Providence, Rhode Island, bound for New York, New York. Setting off down the Providence River and Narragansett Bay, it rounded Point Judith and proceeded through Block Island Sound, where the Larchmont encountered the full effects of a strong gale and large waves. The captain of the Larchmont, George W. McVay—occasionally written “McVey”—who had been in the pilothouse as the ship left the wharf and sailed out to sea, left to make his rounds, leaving control of the ship in the hands of his officers. After his inspection of the ship, the captain returned to the pilothouse and spoke with his officers and then went to his cabin. Within a short time, several blasts of a steam whistle sounded, startling Captain McVay.

The captain hurriedly made his way to the pilothouse. As he looked eastward, he saw a schooner moving along under a strong wind. Several more blasts from the Larchmont’s steam whistle were sounded. In the pilothouse, the pilot and quartermaster spun the wheel hard to port in a frantic effort to avoid the collision. As the Larchmont responded slowly to the pilot’s efforts, the schooner Harry Knowlton suddenly rose upward and headed straight for the steamer. It seemed to be traveling at the speed of the gale that filled its sails. Before another blast from the steam whistle could be sounded, the schooner Harry Knowlton crashed violently into the port side of the Larchmont, eating its way into half the breadth of the large steamer.

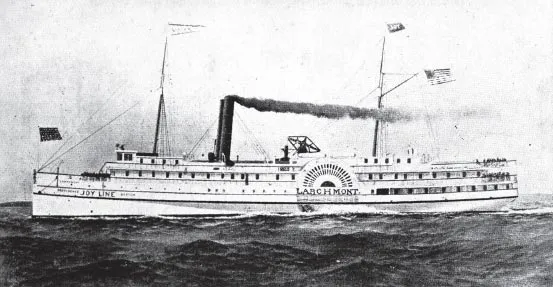

The steamer Larchmont of the Joy Line, out at sea.

Passengers on the upper deck of a ship, while the ship is underway.

The velocity of the impact from the schooner tore through the vitals of the Larchmont and then the schooner sat helpless within the innards of the crippled steamer. Acting like a plug in a bottle, the schooner held tight, keeping out the ocean. The raging seas rocked the two vessels, and after a short time, the violent seas separated the two vessels. When the schooner Harry Knowlton became free from its entanglement, it slid away, and the raging ocean rushed into the gigantic hole in the Larchmont that was left by the impact. With no watertight compartments that could be closed, the steamer’s fate was sealed. Ocean water filled the cargo hold of the steamer within minutes. The rushing water sounded like a freight train as it made its way toward the boiler room. As the water hit the boiler’s red-hot skin, enormous clouds of steam rose up.

The panic-stricken passengers on deck watched in amazement as the events unfolded. Many of the passengers who were resting in their cabins were thrown from their bunks during the collision. Numerous passengers came streaming out from their cabins and onto the decks, reacting out of fear, believing a fire had broken out onboard the ship. Very few had taken the time to properly cloth themselves during the turmoil.

The zero-degree temperature seemed to go unnoticed by many at first, but it soon became evident that the frigid weather threatened the passengers’ safety. Many of them found it impossible to return to their rooms, which were now flooded, making their belongings unusable. The ship, now floundering, was sinking rapidly. The dire situation eroded the professionalism of the crew aboard the Larchmont. Preparations to lower the lifeboats and rafts began. The extreme cold numbed the hands and feet of the passengers and crew alike, turning noses and ears white with a bitter frost.

As the lifeboats and rafts were loaded haphazardly—many being only partially filled as they were pushed away from the ship—chaos began to reign as the shrieks of the drowning filled the air.

Those who considered themselves lucky to find refuge in the lifeboats soon understood their situation and the fact that the cruel pain of the violent weather that they would endure had just begun. As the small lifeboats bobbed along in the high seas, spray from the ocean rose up and covered them with each wave. Before long, a thin coating of ice enveloped the boats, leaving those partially clothed in mortal pain.

The nearest point of land was Fisher’s Point, to the west of where the steamer went down. All the struggling crafts headed in that direction. The men at the oars, many half dead, strained against the unrelenting gale. Before long, the crafts became separated, and each faced its own ordeal. The first word of the disaster came to Block Island at 6:00 a.m., brought by a young man named Fred Hiergesell, who survived the collision and departed the sinking ship in a lifeboat. The boat he was in capsized just offshore of Block Island. Once in the water, the young man swam frantically to shore. Suffering physically and mentally from the ordeal, he made his way to the North Lighthouse near where he came ashore. At the lighthouse, he pounded on the door, half crazed. Elam Littlefield, the lighthouse keeper, was awoken, and he quickly dressed. Opening the door, Littlefield found a young man in a pitiful condition. As the young man entered, he collapsed, muttering, “More coming, more coming.” The lighthouse keeper woke others, and they began tending to the young man, now half-conscious, while he continued muttering, “More coming.”

The Cumberland while under steam power.

A chilling scene occurred aboard the captain’s lifeboat that night. As the men aboard struggled at the oars, which had frozen because of the cold temperature, one man found the situation unbearable and pulled out a knife from his coat pocket and plunged it into his throat. The man then fell from his seat to the floor of the boat while all looked on in disbelief.

Once the lifeboat floated ashore at Block Island, assistance was given to those aboard, none of whom could walk because of their badly frozen feet. All the survivors were carried from the lifeboat to shelter. Those who assisted with the rescue soon realized the severity of the ordeal for those in the lifeboats. The lifeless body of the man who could not endure the situation was gently removed from the lifeboat and brought inland.

At another location on Block Island, a surfman from the United States Life-Saving Service, while on beach patrol, noticed a surreal image emerging from the surf. The visibility that morning was poor, and a heavy mist covered the ocean. As the patrolman made his way around the northwest side of Block Island, a man caked in ice staggered out of the surf and onto the beach. The surfman brought the man to the lifesaving station for aid. A short time from when the man walked ashore, a lifeboat full of frozen bodies drifted out from the fog and onto the beach. Word spread of the situation, and within hours, the majority of the population of the island came to the shore to help. From the direction of the disaster, bodies began floating ashore one by one. Those who gathered to assist began the daylong task of hauling the unfortunate ashore from the icy surf, many of who encased in inches of ice.

Retrieving bodies along the beach on Block Island.

Many of the bodies had their arms raised as if they were swimming, retaining their forms as they became frozen in the act by the severe weather. Sympathetic tears from the islanders fell on the faces of those being gently placed on the wagons for the journey inland. The few that came ashore alive were well cared for and given the best medical attention the island could offer.

The lifesaving stations at New Shoreham and Sandy Point were used as temporary morgues. The frozen bodies retrieved from the ocean were laid out on the floors. Many of those on the island who assisted in the rescue would never forget the gruesome scene of the many bodies with their twisted limbs frozen in place. The lifesaving stations were also used as hospitals. Carts and beds were set up in the sleeping and living rooms of the stations.

The pitiful condition of those being treated at the makeshift hospital tore at the hearts of those rendering aid. Many of the survivors suffered from severe frostbite. Some of them needed fingers or hands amputated. Compounding the physical ailments of the survivors were the emotional injuries from that horrible night. Many of those being cared for could not sleep with the images of the terror from the prior night running through their minds. At the hospital, cries of anguish filled the air that first night.

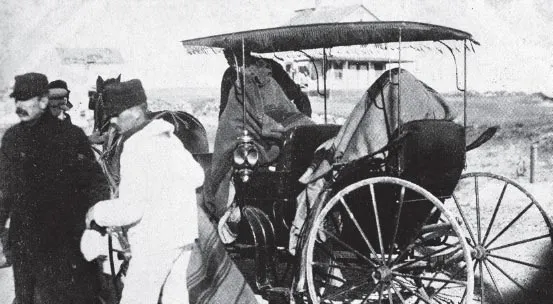

Transporting survivors from the New Shoreham Life-Saving Station.

Days after the disaster, the steamer Kentucky of the Joy Line was dispatched to Block Island to pick up the survivors as well as the bodies of the unfortunate who died in the accident. Relatives of the deceased gathered in Providence to await the arrival of the funeral ship Kentucky, which carried the bodies of their loved ones. The Kentucky arrived much later in Providence than planned, due to the difficulties in getting the bodies aboard ship at Block Island.

The bodies had to be transported five miles by wagon to where the Kentucky was located and then loaded aboard. One of the survivors wouldn’t board the Kentucky for the trip to the mainland. Sadie Golub, traumatized by the events of that dreadful night, refused to go aboard the Kentucky or any other ship, afraid that another incident might happen once out to sea. Needing proper medical treatment for potential pneumonia and frostbite, she was finally persuaded to make the trip. The Kentucky made additional trips to the island for the purpose of bringing back bodies that were found later.

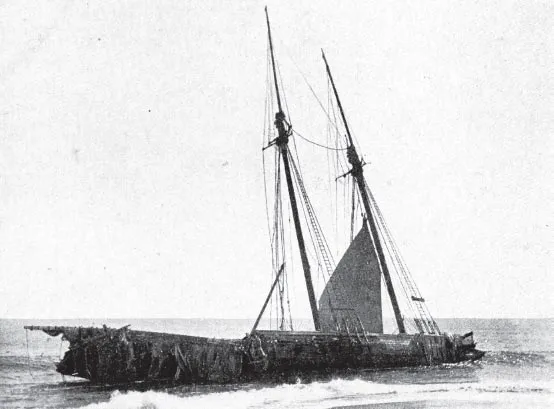

The schooner Harry Knowlton, after backing away from the collision, quickly began taking on water. Captain Frank T. Haley and his crew of six quickly began pumping out the ship in an attempt to keep it afloat. The crew managed to sail the schooner toward the shore, but before long, all efforts to save the ship were abandoned.

Remains of the schooner Harry Knowlton off Watch Hill, Rhode Island.

The crew then boarded the lifeboat, pushed away from the ship and attempted to row ashore. The men, enduring the extreme cold and heavy surf, struggled to row their lifeboat toward the beach. While floundering just off the beach, a surfman from the Quonochontaug Life-Saving Station spotted them and came to their aid. Once on the beach, the crew of the schooner walked about three miles to the Quonochontaug Life-Saving Station where they were given food and shelter. The men of the Harry Knowlton were very fortunate; had it not been for the crew’s proficient seamanship, their fate might have been similar to that of those onboard the Larchmont.

FEBRUARY 12, 1907

As the residents of Block Island and many living along the shores from Westerly to Providence, Rhode Island, awoke to the news of a tragedy that had occurred while they slept, concern quickly spread. They were some of the first to hear the news of the tragedy that befell the steamship Larchmont. Details of the unbelievable events that took place just off shore the night prior trickled in. As the day wore on, it became evident that there had been a great loss of life. Much of the news of the collision spread neighbor to neighbor, and many hearing of the tragedy had trouble digesting some of what they were hearing. As the details were put in print, those skeptics became aware of the facts.

News accounts began with the basic details of the incident: that the Larchmont left the wharf at Providence, Rhode Island, around 7:00 p.m. on February 11, 1907, bound for New York, New York, with an estimated one hundred passengers. The vessel was also half loaded with a cargo of mixed freight.

The beginning of the voyage was routine as the Larchmont navigated its way down the Providence River, mastered by George W. McVay. Once the Larchmont passed Sabin’s Point, the control of the vessel was given to the first pilot John L. Anson; this was an established custom. This procedure was in full compliance with the provisions governing the navigation of steam vessels. Soon after Captain McVay gave command to the first pilot, he began a routine inspection of his ship and its freight. From the pilothouse, he proceeded to the salon deck and then to the main deck.

As a tradition, he would stop and talk to members of the crew. Captain McVay would then make his way to the engine room, also located on the main deck. After talking with the engineer, the captain would move aft to the quarterdeck to where the salon watchmen were located. He would stop at the purser’s office to speak with the steward. On that day, Captain McVay left the purser’s office at 10:40 p.m. and headed for his room, which adjoined the pilothouse on the upper deck.

On entering the pilothouse, Captain McVay conversed with first pilot John Anson...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. NIGHT OF TERROR

- 2. THE SCHOONER HARRY KNOWLTON

- 3. THE PASSENGERS AND LIFESAVERS

- 4. INVESTIGATION AND OFFICIAL REPORT

- 5. THE JOY LINE

- 6. OTHER DISASTERS

- 7. POPULAR DESTINATIONS

- Bibliography

- About the Authors