![]()

Many a One of Us Will be Cold Tomorrow Night

CHAPTER ONE

JULY 21, 1861

On July 20, 1861, tall, bearded Pvt. Arthur Alcock walked the makeshift campgrounds of the 11th New York Fire Zouaves at Centerville. He had arrived about 10:00 p.m. after obtaining hospital supplies at Alexandria for the regimental surgeon, Dr. Charles Gray. Alcock visited the officers of the different units, getting a cup of coffee and a roasted potato from Capt. Michael Tagan of Company D along with some good conversation from the sleepless men. Each one knew that the next day would bring a fight, the Fire Zouaves’ first one. The “bespangled sons of Mars,” now weary, footsore, and hungry, contemplated their immediate future. Lieutenant Daniel Diver, who did not know that he was enjoying his last night alive, accompanied Alcock in his ramble.

The distinctive uniforms of the Zouaves—such as the one on display at the Fredericksburg Battlefield Visitor Center—were based on a French design. (cm)

The two men discussed the condition of the troops, commenting on their good spirits “in view of the expected fight” the next day. In Alcock’s journal, written during his imprisonment in Richmond after the first battle of Bull Run, wrote, “poor Diver said to me, ‘Many a one of us will be cold to-morrow night.’ Who will say that ‘coming events do not cast their shadows before?’”

Before the third week in July, Union and Confederate armies had prepared somewhat for the sad fact that the coming altercation would probably result in casualties of some variety. The firing on Fort Sumter three months earlier was an anomaly; it had produced no deaths attributable to the actual fighting. No one was naive enough to think this trend would continue, so the Federals prepared hospitals in Washington, D.C., for incoming wounded. Wagons were equipped to carry medical supplies to the field of battle, and the Union had purchased both two- and four-wheeled varieties to be used as ambulances; the larger one would return to the capital with wounded who had been triaged on the scene. The Confederacy brought similar wagons, planning to evacuate its wounded to hospitals in and around Richmond. On both sides, women staffed these makeshift facilities.

No one had really thought what to do with any dead men that might actually accrue during the brief kerfuffle. After all, one Confederate could easily whip from three to 10 Yankees; or, if one preferred, one Yankee just had to stand his ground and the blustering Rebels would run out of things to brag about and retreat. It would be one short, decisive battle, and then the war would be over—or so many thought.

A walking trail across Matthews Hill follows part of the Federal advance, which came from the right of the photo toward the fence. Somewhere in this area on Matthews Hill, the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry lost its officers. (ro)

The first battle of Bull Run, also known as First Manassas, was fought on July 21, 1861, near the city of Manassas, Virginia, not far from the Federal capital in Washington. It was the first major battle of the Civil War. Union forces fought well early in the day, but the Confederate forces, strengthened by reinforcements that arrived by rail, eventually won the battle. Each side had about 30,000 inexperienced troops led by equally inexperienced officers. The Confederate victory was followed by a disorganized Union retreat.

In hindsight, the casualties were light, at least compared to what the future held. Approximately 400 Confederates were killed and 1,600 wounded. Union forces had comparable casualty rates: 460 killed and 1,124 wounded, with an additional 1,312 Union soldiers listed as missing and captured. Even at the time, Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson referred to it as a “tupenny skirmish,” but these deaths deeply affected communities in 20 states, both Northern and Southern. The majority of casualties were from either New York or Virginia. Now, as one Virginian said, “War was no longer funny.”

Both Union and Confederate dead lay exposed to a terrible rainstorm that began the evening of the 21st and continued all the next day. Federal troops had rather abruptly left the battlefield, being unceremoniously routed by the Confederates after several hours of intense fighting during which the outcome of the battle was uncertain. At the end, however, it was certain—the Federal forces had lost the first engagement of the war.

Private Alcock was the orderly for Dr. Gray, the regimental surgeon for the 11th New York Fire Zouaves. Due to his position as a non-combatant, he was able to observe his surroundings, and he gave his report later on, in the journal he wrote in prison. Dr. Gray and several other surgeons had set up a field hospital at the Sudley Methodist Church, on the upper northwest part of the battlefield. As the battle wound down outside the little church, Alcock and the others realized that, although they were in danger of becoming prisoners, they could not stop their bloody work. “In the church,” Alcock wrote, “the scene of human suffering was terrible. Every part of the floor was covered with the wounded—dying and dead…. So close together did the wounded lay upon the floor, that it was with the greatest I could pick my way through them.”

Judith Henry, too infirm to evacuate her home during the battle, became the first civilian casualty of the Civil War when an artillery shell exploded in her bedroom, killing her. After the battle, her family buried her in a small plot behind the house, where visitors to the battlefield can still pay their respects. (cm)

Cries of “Water, water, for God’s sake!” and “Oh! For Heaven’s sake don’t step on me,” rang everywhere. No amount of pleading on the parts of the doctors, their assistants, or the wounded kept the Confederate cavalry lieutenant in charge of rounding up prisoners in that part of the field from forcing all who could walk, regardless of situation, to begin the eight mile trek to Manassas. Many men were left behind, and the little group of Federals “passed by scores of dead men and horses, many of them horribly mutilated.” The grim work of burial would begin almost immediately, even in the rain.

Usually burial work was the job of slaves, but there were far too many bodies for the few slaves available in the Manassas-Centerville area to bury them quickly. This was the first battle, after all, and sometimes a friend or brother wanted to perform this service for those about whom he cared. One Confederate soldier decided he would go back to the battlefield to find his friend Blue. After he located Blue’s body, he used a hoe and a spade to dig a grave in the orchard next to Mrs. Henry’s house. As he worked, another Confederate came up to him and asked to borrow the tools, as he had located his brother’s remains and wished to bury him as well. The rain poured down over the two men and their sad burdens, so the two agreed to work together to dig a hole large enough to accommodate both dead men. “So we buried them that way,” the first soldier recalled, “and gathered up some old shingles to put over the bodies.”

Battlefield visitors look for remains on the Manassas battlefield; through the trees, Sudley Church stands on the ridge in the background. (loc)

Because the Confederates had won the battle, they were left in charge of the field. The burials were done hastily, with little attention to detail, and within three days the field was considered cleared, although a spot of rain might uncover a decomposing foot or hand. The dead, however, did not necessarily rest in peace.

* * *

Many men who died at the First Bull Run have become famous and their remains are identified and well-cared for. Confederate Gen. Barnard Bee, who gave Brigade Commander Thomas Jackson his sobriquet “Stonewall,” and Confederate Col. Francis Bartow, who died after having been hit in the chest by a projectile while leading Col. Lucius J. Gartrell’s 7th Georgians up Henry House Hill, are two examples. Bee’s and Bartow’s remains were taken back to Richmond via train, given services at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, and then sent to their families for burial.

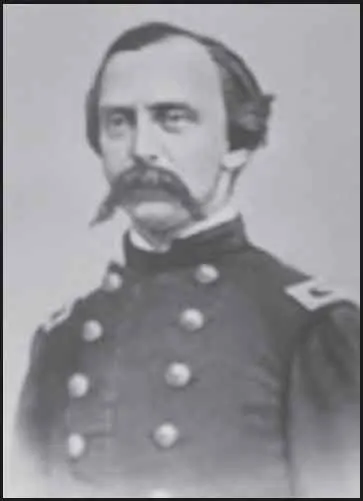

A monument to Col. John Slocum (above) was erected by the Grand Army of the Republic at Swan Point Cemetery in Providence, Rhode Island. (mg)

Union Maj. Sullivan Ballou, of the 2nd Rhode Island, and arguably the most romantic man in either army, was not so lucky. He and several other Rhode Island officers had been too badly injured to move during the Union retreat, and were left at the field hospital within Sudley Church. The men were then moved to the Thornberry house, where Rhode Island Col. John S. Slocum died on July 23 and Ballou on the 28th. They were buried, side-by-side, near Sudley Church. Rumors had surfaced in the winter of 1861 that some Confederates had returned to the battlefield and exhumed Federal bodies, the Rhode Island officers being among those who were desecrated. Rhode Island Governor William Sprague and his party of 70 politicians and soldiers left Washington, D.C., on the rainy morning of March 19, 1862, to check the truth of the rumors and retrieve the bodies of their officers and men, if possible.

“The indications are very strong that we shall move in a few days—perhaps tomorrow. Lest I should not be able to write you again, I feel impelled to write lines that may fall under your eye when I shall be no more….

“If it is necessary that I should fall on the battlefield for my country, I am ready. I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in, the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage does not halt or falter. I know how strongly American Civilization now leans upon the triumph of the Government, and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution. And I am willing—perfectly willing—to lay down all my joys in this life, to help maintain this Government, and to pay that debt….

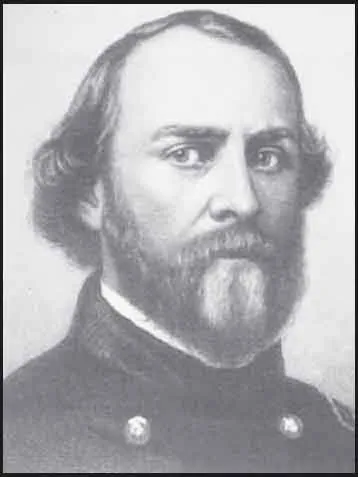

Sullivan Ballou (above) gained national attention for modern audiences when Ken Burns featured him at the end of the first episode of his 1990 film The Civil War. Ballou wrote a poignant letter to his wife, Sarah, just days before being killed at the battle of First Manassas.

“I cannot describe to you my feelings on this calm summer night, when two thousand men are sleeping around me, many of them enjoying the last, perhaps, before that of death—and I, suspicious that Death is creeping behind me with his fatal dart, am communing with God, my country, and thee….

“Sarah, my love for you is deathless, it seems to bind me to you with mighty cables that nothing but Omnipotence could break; and yet my love of Country comes over me like a strong wind and bears me irresistibly on with all these chains to the battlefield….

“And hard it is for me to give them up and burn to ashes the hopes of future years, when God willing, we might still have lived and loved together and seen our sons grow up to honorable manhood around us…. If I d...