![]()

Chapter 1

Along the Rivers

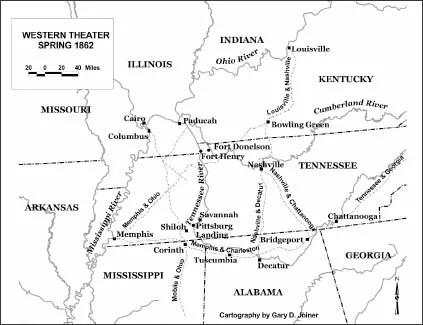

A POET MIGHT DESCRIBE them as arrows running though the heart of the Confederacy, but to the military and political leaders of the North and South back in 1861, the Cumberland, Tennessee, and Mississippi rivers represented something much more prosaic, yet vital: the probable difference between victory and defeat in the American Civil War. Besides serving as a major peacetime avenue of trade for the western states, these rivers dissected and divided much of the richest area of the South. With its tremendously greater industrial resources, the North could easily utilize these rivers as avenues of invasion into the heartland of the South, striking at the population centers of Tennessee, at the railroad lines connecting the Confederacy, and at the industrial centers that were beginning to bud, notably Chattanooga, Nashville, and Atlanta. The Confederacy, lacking the industrial facilities to build a powerful river fleet, would be forced to utilize river fortifications as a defense against a Northern push down the lines of these rivers.

One of the prizes in the war in this heartland region was the all important border states, Kentucky and Missouri. Not only for their geographical locations, but also as a fertile field for recruiting and obtaining munitions, these states were of the utmost importance to both sides.

The geographical features of this heartland region, where the war was slowly developing, were significant. The two great rivers, the Tennessee and Cumberland, intersected the region, and would be of great use as a means of moving troops and supplies with minimum cost. The Tennessee was navigable from its mouth, through Western Kentucky and Tennessee, and into the northern part of Alabama as far as Mussel Shoals, while the Cumberland could be navigated far up beyond Nashville. In the eastern region were the Cumberland Mountains which could be crossed at certain passes, the most important of which was Cumberland Gap, if the Union forces could develop a strong enough army with a secure logistics base to immediately advance and drive out the comparatively small Confederate force in the area. The Tennessee and Georgia Railway ran up the valley of these mountains into Virginia, making it one of the main lines of communications between the Southern armies operating in that region and the Gulf States. At the city of Chattanooga, in East Tennessee, Unionist territory, this railway connected with the Georgia Central Railroad, which led into the heart of Georgia, and with the Memphis and Charleston, which passed into northern Alabama and Mississippi and Memphis, Tennessee. From Louisville, Kentucky, the Louisville and Nashville line ran southward through Bowling Green a hundred miles and to Nashville, seventy miles farther.

![]()

![]()

From General Albert Sidney Johnston’s base at Bowling Green, the Memphis and Ohio passed through Clarksville, Paris, and Humboldt, Tennessee, and to Memphis, two hundred and forty miles away. Running from Paris, Tennessee, there was a branch through to Columbus, which was about a hundred and seventy miles by rail from Bowling Green, the center of the Confederate line. There was a double line of railroads directly from Humboldt into the state of Mississippi. From Nashville, Tennessee, the Nashville-Decatur line ran southward into Alabama, while the Nashville and Chattanooga connected Nashville with the Confederate railroad center at Chattanooga. As long as General Johnston could hold the line from Bowling Green to Columbus, he not only plugged off the Cumberland, Tennessee, and Mississippi rivers against a Unionist advance, but he also protected this powerful and important railway system. An advance overland by either army was apt to be an extremely difficult proposition, for the roads in Kentucky and Tennessee were usually of the ordinary country type, which was passable in the summer, but was very difficult to move over when the rains came in winter and spring.1

Besides the transportation system, there were other pressing reasons why the South had to defend this heartland region. By retaining control of the region, Southern authorities could eventually draw large numbers of conscripts and drafted troops. If the Union army could occupy this region, then persons of lukewarm sympathy could be drafted into the Federal army. Also, mines in the extreme southeastern part of Tennessee, at Ducktown, furnished 90 percent of the copper mined in the Confederacy. Furthermore, Tennessee, with seventeen furnaces smelting twenty-two hundred tons of iron ore annually in 1860, was the largest producer of pig iron in the South.2 The Kentucky-Tennessee region was also tremendously important for the large quantities of food stuffs produced. In 1860, Kentucky produced almost seven and one-half million bushels of wheat, six times that of Alabama, while Tennessee produced five and one-half million bushels as compared to less than six hundred thousand raised in Mississippi. In the same year, Kentucky produced sixty-four million bushels of corn, and Tennessee produced fifty-two million as against twenty-nine million for Mississippi and thirty-three million for Alabama. This meant the Kentucky-Tennessee region not only produced adequate supplies for its own use, but enough to export, potentially, to other regions of the Confederacy, both for military and civil use. This region was also vastly important for livestock. In 1860, Kentucky was listed in the census records as possessing three hundred and fifty-five thousand horses, one hundred and seventeen thousand mules and asses, and more than a third of a million sheep, while Tennessee followed only slightly behind with two hundred and ninety thousand horses, one hundred and twenty-six thousand mules and asses, and three quarters of a million sheep. At this same time Alabama only had a hundred and twenty-seven thousand horses, one hundred and eleven thousand mules and asses, and three hundred and seventy thousand sheep, while Mississippi followed with one hundred and seventeen thousand, one hundred and ten thousand, and three hundred and fifty-two thousand, respectively. Thus not only was this region a bread basket, but it also would be extremely useful for supplying remounts for Confederate cavalry and work animals for Confederate ordnance and commissary depots.3 Tennessee also supplied more than a quarter of the scant leather supply that would be available in the Southern Confederacy.4 Economics as well as strategy dictated that the Confederacy must hold the line in Kentucky and Tennessee.5

It naturally followed that whoever could gain control would be in a much better position both militarily and politically. The governors of Tennessee and Kentucky both tended to be pro-secessionist, but at the outbreak of war the legislators tended to either favor a policy of neutrality or were in favor of remaining within the framework of the Union. Using illegal or extra legal means, pro-Unionist forces quickly gained control of the Missouri state government, seized most of the large stocks of munitions lying within the state, and launched an offensive to clear out pro-Confederate forces from the state. After a preliminary engagement at Boonville, Missouri, Unionist forces led by Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon began a move southward.

Brigadier General Franz Sigel was defeated in a minor action at Carthage, Missouri, but managed to link up with Lyon in time to attack the Confederate army in Missouri, which was led by Brigadier General Ben McCullough, and the Missouri State Confederate Guard, commanded by Brigadier General Sterling “Pap” Price. Lyon was killed in battle at Wilson’s Creek, Missouri, on August 10, 1861, and his numerically smaller army was forced to retreat in one of the bloodiest actions for its size in the entire war. The following month, in September, Price succeeded in capturing Lexington, Missouri, after a two weeks’ siege, but lack of equipment and numbers forced the pro-secessionist forces to withdraw southward.

In Kentucky, the situation was even more complex. Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner commanded the Kentucky State Guard, a well-trained and organized military force of about twelve thousand men, largely pro-Confederate in sympathy. Buckner, the soul of honor, refused to use his position to advance the cause of the Confederacy and entered into an agreement with Major General George B. McClellan to maintain Kentucky’s neutrality. Both sides immediately began raising troops from this state. The Confederates, who were theoretically at least in the eyes of most Northerners, Rebels, unfortunately insisted on acting in the most legal and officious manner possible, while their Northern foe, who supposedly represented the forces of good order and legality, acted with almost true revolutionary zeal. Arms and munitions were brought into Kentucky from Northern arsenals, and several bodies of pro-Union Kentucky troops were soon organized, the most important at Camp Dick Robinson, in Northern Kentucky, commanded by one of the most interesting figures of the war, Brigadier General William Nelson, a naval officer turned soldier in the emergency.

The Confederates drew troops from the state, but they set up their camps across the Kentucky line in the friendly state of Tennessee, which had seceded in June. The Kentucky situation finally exploded on September 3, 1861, when Major General Leonidas Polk led Confederate force across the state line and occupied Columbus, which he immediately began fortifying into one of the strongest Confederate positions in the West. In retaliation for the act, Brigadier General U. S. Grant led a small Union force south, occupying Paducah on the following day. Polk’s act was militarily important because it did give the Confederates a good base of operations for their left flank in Kentucky, but it was politically unfortunate because it put on the South the stain of first invading a neutral state and alienated many Kentuckians, who might otherwise have been more sympathetic to the Southern position. The line of Confederate forces in Kentucky was soon stabilized, running from Bowling Green in the center, left to Polk’s newly acquired position at Columbus, and to the right roughly to the vicinity of Cumberland Gap. Confederate headquarters were at Bowling Green, on the south bank of the Barren River, where the railroad from Nashville to Louisville crosses. This position also enabled the Southerners to use the Mobile and Ohio Railroad, which crossed over into Tennessee, enabling the Confederates to use rail communications between their center and their left. Across the Mississippi River, the Confederates occupied and began fortifying New Madrid, Missouri, as well as Island No. 10, which actually was an island at a point between the Tennessee and Missouri shores.6

Even before Tennessee seceded Union authorities had already begun work on building a fleet capable of potentially dominating this heartland region. At Cairo, Mound City, and St. Louis, Union ironclad warships, as well as wooden gunboats, were quickly constructed and outfitted. Across half a dozen states Confederate and Union generals raised troops, collected munitions, and tried frantically to put their forces together in some reasonable state of preparation for the fighting that sooner or later would break out. At this early stage in the war, both sides were handicapped by the lack of practical experience, as well as sufficient quantities of supplies and weapons. The South naturally suffered most in this department, lacking funds to buy materials in Europe and resources at home with which to build war equipment, but even the Union forces were often inadequately equipped in the first days of the war. Neither side was prepared to launch any kind of major offensive operation at this time, and most Union leaders were too happy to retain control of Missouri and Kentucky.

After the fall of Fort Sumter, Major Robert Anderson, Kentucky-born but loyal to the Union, achieved the status of a national hero even though he had been forced to yield his position, after a two day bombardment, to Brigadier General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard. Because of his Kentucky connections, Lincoln and other Washington officials thought it would be politically expedient to send him to command in Kentucky once Union and Confederate forces had moved into the state. Anderson was in ill health, and he soon asked to be relieved after a little more than a month in service. On October 7, the hero of Fort Sumter was formally relieved of his command by Brigadier General William Tecumseh Sherman, who after his services at the Battle of First Manassas had been appointed to command an infantry brigade at Lexington, Kentucky. Sherman held this command for a little more than a week before he became involved in his famous discussion with Secretary of War Simon Cameron over just how many troops would be needed to suppress the rebellion and crush the Rebels in the Mississippi and Tennessee valleys. The following month Sherman was replaced by Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell as head of the Department of the Ohio. Sherman was shunted off for a short rest, and was out of the main-stream of events for some weeks while he recovered control of his nerves.7

With Buell in command in central and eastern Kentucky and the adjacent Northern states and Major General Henry W. Halleck in command of the Department of the West across the river and the district of western Kentucky, it would seem that the Union army was suffering from a serious error in divided command. Actually the division of the West in the various departments was the product of the thinking of the new General-in-Chief of the Union Army, George Brinton McClellan. On November 9, just eight days after McClellan assumed his new position as head of the Union army, he divided the extensive Western Department into the Department of Kansas and Missouri. The latter included not only Missouri but the Western states of Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, Arkansas, and the segment of Kentucky lying west of the Cumberland River. Lincoln’s home state of Illinois had been in the Western Department since the third of July, but all of Kentucky, with Tennessee, had comprised the old Department of the Cumberland, though forces from the Western Department had been stationed at Paducah and Cairo.

With a large but motley collection of half-trained armies scattered on both sides of the Mississippi River, the stage was practically set for the opening of the real war for the Mississippi and Tennessee valleys. But if the stage were set, the casting of the roles of the leading actors was not complete. Most of the characters were on hand, but no one had been picked to direct the play. Major General John Charles Fremont, the famous Pathfinder of Western explorat...