This is a test

- 1 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Complete Guide to Postnatal Fitness

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

An updated third edition of the guide for new mums, fitness leaders and physios on how to regain fitness following the birth of a baby. This Complete Guide includes:

- exercises

- advice

- relevant anatomy and physiology All clearly explained, fully updated and packed with exercises. Includes new guidance and up to date references, and all illustrations replaced with new photographs.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Complete Guide to Postnatal Fitness by Judy DiFiore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Sport & Exercise Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

STRUCTURE AND FORM | 1 |

THE PELVIS

Structure of the pelvis

The pelvis is made up of four bones: two hip bones, plus the sacrum and the coccyx. Each hip bone is made up of three fused bones: ilium, ischium and pubis. The acetabulum, the deep socket for the head of the femur, is formed by the unification of all three bones.

• The ilium is the large wing-shaped part of the pelvis providing a broad surface area for muscle attachment. The upper border, the iliac crest, can be felt when the hands are placed on the hips. The bony points at each end of the iliac crest can be felt at the front of the pelvis, as the anterior superior iliac spines (ASIS), and at the back, as the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS). These are useful landmarks when checking correct postural alignment as they should be approximately at the same level.

• The ischium is the thick, lower part of the pelvis leading down to the ischial tuberosities, commonly referred to as the ‘sit bones’.

• The pubis is at the front of the pelvis where the two pubic bones join to form the symphysis pubis at the top and the pubic arch underneath.

• The sacrum is a triangular-shaped bone made up of five fused vertebrae. It is joined to the ilium by the sacroiliac joints, which are positioned on either side of the sacrum.

• The coccyx consists of four fused vertebrae that are joined to the sacrum at the sacrococcygeal joint.

Figure 1.1 The bones of the pelvis

The joints of the pelvis

The pelvis is made of two halves that join at the front at the symphysis pubis and at the back at the sacroiliac joints.

• The symphysis pubis (SP) is situated at the front of the pelvis where the two pubic bones meet. Separated by a pad of cartilage resembling a vertebral disc, the joint is approximately 4mm wide and has minimal movement, except in pregnancy.

• The sacroiliac joints (SIJ) join the spine to the pelvis (one on each side) between the ilium and the sacrum. The strongest joints in the body, they transmit forces from the upper body and ground reaction forces from the lower extremities. The SIJ allow limited backward and forward movement during flexion and extension of the trunk. During gait the joints lock alternately to allow transmission of body weight from the sacrum to the hip bone. They are synovial (gliding) joints, held together by both anterior and posterior ligaments. By 30 years of age the SIJ lose their synovial quality and become more cartilaginous (Mercer 2009).

• The sacrococcygeal joint, situated between the sacrum and the coccyx, is worth a mention as it allows a small amount of flexion and extension of the coccyx. This is necessary during labour to increase the size of the pelvic outlet.

Figure 1.2 Joints of the pelvis showing ligaments

Form and force closure

These are mechanisms to prevent excessive movement at a joint. Form closure relates to the structure of the joints, bones and ligaments; force closure is the activation of muscles and fascia, together providing stability for a joint. These mechanisms are particularly relevant to pelvic stability during pregnancy.

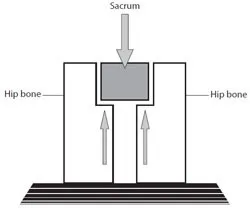

Form closure of the pelvis

The structure of the SIJ provides excellent form closure. The triangular-shaped sacrum is wedged in between the two hip bones, securing its position, and the irregular shape and coarse texture of the bony surfaces interlock with each other to help close the joint. The inner surface of the joint is covered in smooth cartilage to promote glide. Very strong ligaments provide additional support.

Figure 1.3 Form closure of the pelvis provides a natural compression of the joints

The SP has less form closure as the joint is relatively flat. As a cartilaginous joint, it has no synovial capsule – the two ends have ‘grown together’ and are held together by fibrocartilage. Lee (2007 (i)) suggests it is more vulnerable to shearing forces than the SIJ. Its stability is dependent on the correct alignment of the SIJ and it relies more on the muscular system for support.

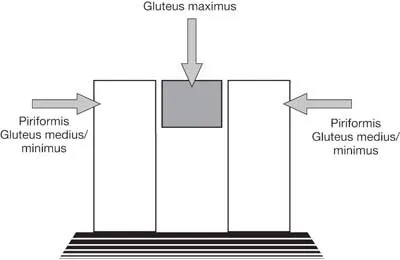

Force closure of the pelvis

As discussed above, the structure of the pelvis provides a natural compression of the joints but a degree of mobility is necessary to allow movement to occur. Force closure is the action of muscles around the joints to increase compression at the moment of loading. The amount of force closure required depends on the individual’s form closure and the size of the load (Lee 2007 (ii)).

Figure 1.4 Force closure of the pelvis is provided by the muscles surrounding the joint

Numerous muscles attach onto the pelvis to provide increased lumbopelvic stability from all aspects, but the SP and SIJ are not so well served. At the SP, for example, no muscles actually cross the joint; the closest muscular support comes from fibres of the adductor longus and the abdominal aponeurosis that feed into the anterior ligament, which then crosses the joint. At the SIJ the piriformis is the only muscle to cross it. A deep lateral rotator of the hip, the piriformis originates from the anterior side of the sacrum and attaches to the greater trochanter of the femur. The implications for this are discussed later in this chapter.

Effects of pregnancy on form and force closure

Increased joint laxity during pregnancy has major implications for pelvic stability due to its effects on form closure. Relaxin (see below) specifically targets the pelvic ligaments and increases the size of the pelvic outlet in preparation for a vaginal delivery. Lax ligaments reduce joint support, increase range of movement and reduce form closure. Weight gain and pressure from the baby exacerbate the situation. Jain & Sternberg (2005) suggest there is frequently up to 1cm separation of SP during pregnancy and labour.

With the lack of ligamentous support the muscular system is required to step in and assist with the stabilising role and the body relies on this much more during pregnancy. The effects of this are discussed in chapter 2.

Pelvic girdle pain (PGP)

This is an umbrella term for all problems relating to the pelvis that may occur separately or in conjunction with low back pain. It is a common complaint for women during pregnancy, causing considerable disability and distress (Gutke et al. 2006) and is believed to occur in one in five pregnant women (ACPWH 2007). PGP is associated with changes to form and force closure mechanisms during pregnancy and is discussed in chapter 6.

Relaxin

What is relaxin?

Relaxin is a hormone produced in both pregnant and non-pregnant women (Bani 1997). In non-pregnant women and those in the early stages of pregnancy it is produced by the corpus luteum, which is a yellow mass left behind in the ovaries following ovulation. In the second trimester the placenta and the decidua take over production. Relaxin levels peak during the first trimester, then fall approximately 20 per cent for the remainder of the pregnancy. Production ceases with delivery of the placenta and resumes with the recommencement of the menstrual cycle. Levels are higher in second and subsequent pregnancies and in women carrying more than one baby.

What effects do increased levels of relaxin have on the body during pregnancy?

The most significant pregnancy changes occur in the collagen component of connective tissue. As one of the principal proteins of connective tissue, collagen provides strength and resistance to pulling forces and is found in bone, cartilage, tendons and ligaments. Elastin, as its name suggests, gives elastic strength to connective tissue. Increased levels of relaxin affect the remodelling structure of collagen by increasing elasticity and reducing strength. Joint stability is particularly affected, as ligaments are unable to provide the same degree of support as before.

The degree of change is variable among women and not just dependent on the level of circulating relaxin (Marnoch et al. 2003). Collagen type, which is genetically determined, is a key factor – women with a higher proportion of weaker collagen type, e.g. hypermobile women, will be more at risk during this time. Increased ligament elasticity allows the pelvic joints a greater range of movement and, together with the forwar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Structure and Form

- 2 Lumbopelvic Stability

- 3 The Abdominal Muscles

- 4 The Pelvic Floor

- 5 The Breasts

- 6 Postnatal Complications

- 7 Preparing to Exercise

- 8 Selected Postnatal Exercises

- 9 Cardiovascular Training

- 10 Resistance Training

- 11 Group Fitness Sessions

- 12 Water Workouts

- 13 Relaxation

- 14 Planning a Postnatal Fitness Session

- 15 Management, Teaching and Evaluation of a Postnatal Fitness Session

- Appendix

- Glossary

- Recommended Reading

- Useful Contacts

- Acknowledgements

- eCopyright