- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Key Concepts in Operations Management

About this book

Key Concepts in Operations Management introduces a selection of key concepts and techniques in the field.

Concise, informative and contemporary, with consideration given to explaining the principles of the topic, as well as the relevant debates and literature, the book contains over 50 concept entries including: Operations Strategy, Managing Innovation, Process Modeling, New Product Development, Forecasting, Planning and Control, Supply Chain Management, Risk Management and many more.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Operations

Operations Management is the business function dealing with the management of all the processes directly involved with the provision of goods and services to customers.

OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT AS A DISCIPLINE

Operations management is both an academic discipline and a professional occupation. It is generally classified as a subset of business studies but its intellectual heritage is divided. On the one hand, a lot of operations management concepts are inherited from management practice. On the other hand, other concepts in operations management are inherited from engineering, and more especially, industrial engineering.

Neither management nor industrial engineering is recognised as a ‘pure science’ and both are often viewed as pragmatic, hands-on fields of applied study. This often results in the image of operations management as a low-brow discipline and a technical subject. Meredith (2001: 397) recognises this when he writes that ‘in spite of the somewhat-glorious history of operations, we are perceived as drab, mundane, hard, dirty, not respected, out of date, low-paid, something one’s father does, and other such negative characteristics’.

This is not a flattering statement, but it is worth moderating it quickly by the fact that economic development, economic success, and economic stability seem to go hand in hand with the mastery of operations management. Operations management is an Anglo-Saxon concept which has spread effectively throughout many cultures, but has often failed to diffuse into others. For example, there is no exact translation of the term ‘operations management’ in French, or at least, not one that is readily agreed upon. This is not to say that French organisations do not manage operations: the lack of a direct translation may be due to the fact that the operations function ‘belongs’ to engineers rather than managers in French culture. In other cultures, however, the very idea that one should manage operations may not be a concern. For example, it is not unusual in some countries to have to queues for two hours or more to deposit a cheque in a bank, whereas other countries will have stringent specifications requiring immediate management attention if a customer has to wait more than five minutes.

If indeed the mastery of operations management is associated with economic success, this means that despite its potential image problems operations management as a practice may play a fundamental role in society. As acknowledged by Schmenner and Swink (1998), operations management as a field has been too harsh on itself, as it both informs and complements economic theories (see Theory).

WHY OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT?

A theory of operations management

The purpose of a theory of operations is to explain:

- why operations management exists;

- the boundaries of operations management;

- what operations management consists of.

Note that the concept of operations predates the concept of operations management. Hunters and gatherers, soldiers, slaves and craftsmen have throughout human history engaged in ‘operations’, i.e. the harvest, transformation, or manipulation of objects, feelings and beliefs. Operations management, as we know it today, is an organisational function: it only exists and has meaning when considered in the context of the function that it serves within a firm or an institution. Thus, in order to propose a theory of operations management we first need to ask ourselves – ‘Why do firms exist?’

In a Nobel-prize winning essay in 1937, Ronald Coase explained how firms are created and preferred as a form of economic organisation over specialist exchange economies. The key tenet of Coase’s theory is that the firm prevails under conditions of marketing uncertainty. It is because of the fear of not finding a buyer, of not convincing the buyer to buy, or of failing to match the buyer’s expectations that an individual economic actor is exposed to marketing risk. When uncertainty exists, individuals will prefer to specialise and to ‘join forces’, seeking synergistic effects in order to cope with uncertainty.

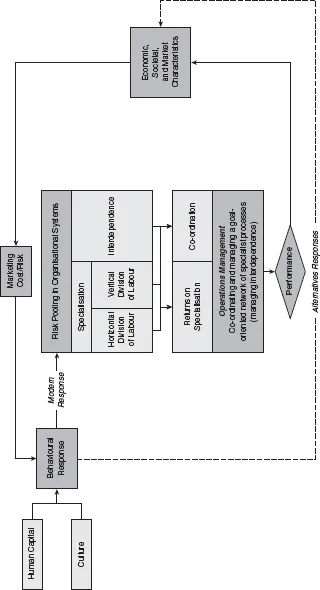

Figure 1 below builds on Coase’s theory and proposes a theory of operations management. It shows that individuals seeking wealth are discouraged from working independently because of marketing risks. In order to reduce their exposure to uncertainty, they will prefer to enter into a collaborative agreement to pool risks in large organisational systems, there by capturing a broad range of complementary specialist skills. The rationale for this behaviour is that it pays to concentrate on what one is good at: a specialist will be more effective at executing a task than a non specialist. Specialisation was the major driver during the Industrial Revolution along with technological innovation. Specialisation patterns are commonly described through the theory of the division of labour.

The division of labour

The division of labour is a concept which can be analysed at several levels. When you wonder about whether to become a doctor, an engineer or a farmer, this choice of a specialist profession represents the social division of labour at work. The emergence of firms has resulted in the further specialisation of individuals with the technical division of labour.

To understand what the technical division of labour implies, consider the example of a craftsman assembling a car before 1900. Without the assistance of modern power tools, of automation, and of technological innovations such as interchangeable parts, building one car could require up to two years to complete. The craftsman was not only a manual worker but also an engineer: he knew perfectly the working principle of an internal combustion engine and what each part’s function was. In a modern assembly factory today, it is not unusual for a car to be assembled from scratch in about nine hours by workers who know very little about automotive engineering. This incredible gain of efficiency is the result of the technical division of labour.

In 1776 Adam Smith published his treatise ‘An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations’, which is often regarded as one of the first business theory books ever written. Adam Smith was a pioneer in documenting how the division of labour would result in considerable productivity gains. Note that his contribution was only to observe that the division of labour was a major factor explaining why some firms and societies were wealthier than others. In other words, Adam Smith documented that such wealth seemed to stem from specialisation. The individuals who transformed the concept of division of labour into management principles were Charles Babbage and Frederick Taylor.

Babbage’s intellectual contribution in 1835 was to build on Smith’s observations and to highlight the benefits of the horizontal division of labour. The horizontal division of labour requires dividing tasks into smaller and smaller sub-tasks. To be more productive, to generate more wealth, one should simplify jobs to their most simple expression.

Figure 1 Theory of operations management

Frederick Taylor, the author of Scientific Management (1911), went one step further. His theory was that effective operations in a business could only be achieved if work was studied scientifically. Taylor’s contribution to management was the introduction of the vertical division of labour. This principle implies that the individual (or unit) who designs a job is usually not the individual (or unit) who implements it. This gave birth to a new field of business studies, called work design (see Work), which was the ancestor of modern process management.

Theory of the division of labour

Although the division of labour was for a long while not considered a theory, both the overwhelming evidence of its existence and recent economic research show that economists may one day finalise the formalisation of a theory of division of labour (Yang and Ng, 1993). Although this constitutes ongoing research, it is possible to speculate on what the fundamental laws of this theory are:

- Law of specialisation: In order to mitigate risk and to benefit from synergistic system effects, firms specialise tasks. It pays to concentrate on what one is good at. Increased specialisation tends to lead to increased performance levels.

- Law of learning and experience curves: The repetition of a task is associated with increasing efficiency at performing that task (see Learning Curves).

- Law of technology: Technology can be used to further increase the efficiency of specialised tasks (see Technology).

- Law of waste reduction: The refinement of an operations process results in the streaming of this process into a lean, non-wasteful production process (see Lean).

- Law of improved quality: Specialisation results in the ability to produce a better quality job (as the division of labour requires individuals to concentrate on what they are good at, it is easier to become better at a specialist task and to avoid performing poorly on peripheral tasks).

Interdependence

Specialisation, however, comes at a price. An individual economic actor will only depend on himself or herself for success. In a firm, though, specialist A relies on specialist B, and vice versa. In such a work context, the potential size of operations systems raises questions about feasibility. When assembling cars, how do you make sure that every single part and component needed is available in the inventory? How do you make sure that every worker knows what to do and how to do it? When running a restaurant, how do you ensure that you keep a fresh supply of all the ingredients required by your chef, given the fact that ordered items will only be known at the last minute? And how do you make sure that everybody is served quickly?

In other words, ‘joining forces’ in the pursuit of wealth is easier said than done. With the shift of work from individuals (craftsmen) to specialist networks, each process and task has been simplified or specialised, but their overall co-ordination has become more difficult. This trend is still taking place today, for example, with the distribution of manufacturing and service facilities across countries to take advantage of locational advantages (the international division of labour). Excellent co-ordination is a fundamental requirement of operations system, as individuals have – in exchange for reducing their exposure to risks – replaced independence with mutual dependence, or interdependence.

Interdependence is why we need operations management. Without operations management, inventory shortages, delays and a lack of communication between design and manufacturing would mean that a firm would never be able to convert risk pooling and specialisation into profits.

- Law of managed interdependence: The higher the interdependence of tasks, the higher the risk of organisational or system failure. This risk can be mitigated, hedged or eliminated altogether through co-ordination processes. Different types of interdependence require different types of co-ordination processes (see Co-ordination).

In a specialised firm, the application of the vertical division of labour means that a restricted set of employees, called the technostructure by Henry Mintzberg, is in charge of designing operations systems and supporting planning and control activities.

Return on specialisation

Today’s economies, and therefore most of our daily lives, take place within the context of specialisation and the resulting need for trade and exchange. How specialisation works is the domain of many economic theories, such as the theory of absolute advantage and the theory of comparative advantage. How specialisation, exchange and trade work together is the domain of much research on macro and international economics.

From an operations management perspective, it is important to appreciate fully the central role of specialisation. Operations management is nothing other than the ‘art’ or ‘science’ of making specialisation patterns work. The law of specialisation states that increased specialisation results in an increased performance level. Like most laws, this statement should be considered carefully: it is only under specific conditions that specialisation will lead to such performance benefits. To better appreciate these conditions, it is a good idea to consider the possible benefits and disadvantages of specialisation.

The benefits of specialisation

These are:

- Increased performance and efficie...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- The Operations Function

- Operations Strategy

- Innovation Management

- Process Management

- Quality

- Inventory

- Planning and Control

- Integrated Management Frameworks

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Key Concepts in Operations Management by Michel Leseure in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.