![]()

1

The Strategic Orientations of Trade Unionism

A Stylized Introduction

In the Nordic countries, trade unions and employers’ organizations are usually described as the ‘labour market parties’. In Britain, it has been traditional to speak of the ‘two sides’ in industrial relations. In many other European countries, the normal term is the ‘social partners’. These differences in vocabulary neatly encapsulate a core concern of this book. In different national contexts and historical periods, trade unions may be seen – by their own members and officials and by outsiders – primarily as economic agencies engaged in collective bargaining over routine terms and conditions of employment; as fighting organizations confronting employers in a struggle between hostile classes;1 or as components of the fabric of social order. In some times and places, they may be perceived in all these guises simultaneously.

The Eternal Triangle: Market, Class, Society

Trade unions in twentieth-century Europe have displayed a multiplicity of organizational forms and ideological orientations. The pluralism of trade unionisms (Dufour, 1992) is associated with conflicting definitions of the very nature of a union, rival conceptions of the purpose of collective organization, opposing models of strategy and tactics. The dominant identities embraced by particular unions, confederations and national movements – themselves reflecting the specific contexts in which national organizations historically emerged (Crouch, 1993) – have shaped the interests with which they identify, the conceptions of democracy influencing members, activists and leaders, the agenda they pursue, and the type of power resources which they cultivate and apply. The clash between distinctive ideological visions of trade union identity has led in almost every European country to the fragmentation of labour movements.

To simplify the analysis of this complex diversity I identify three ideal types of European trade unionism, each associated with a distinctive ideological orientation. In the first, unions are interest organizations with predominantly labour market functions; in the second, vehicles for raising workers’ status in society more generally and hence advancing social justice; in the third, ‘schools of war’ in a struggle between labour and capital (Hyman, 1994 and 1995).

Trade unions as substantial organizations were products of the industrial revolution, even though in some countries they evolved with no significant disjuncture from pre-capitalist artisanal associations. Indeed the very word trade union (which is not translated literally in most European languages) denotes a combination of workers with a common craft or skill. Initially their character and orientations reflected the circumstances of their formation: in most of Europe, brutal resistance by employers to assertions of independence and opposition on the part of the workforce, often accompanied by state repression. Such hostility in turn encouraged in trade unions militant, oppositional, sometimes explicitly anti-capitalist dispositions towards employers; and radical political attitudes which – in circumstances of restricted franchise and autocratic government – were not clearly distinguishable from revolutionary socialism. This, not surprisingly, reinforced the antagonism of unions’ opponents.

Yet trade unions survived repression; over decades, indeed generations, survival encouraged and was in turn supported by some form of accommodation. Its features varied between (and often within) countries; but typically the latter half of the nineteenth century saw the more successful unions marginalizing or ritualizing their radicalism, and seeking understandings with employers on the basis of the maxim of ‘a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work’ – a principle whose concrete meaning, Marx complained, was determined by the operation of the (bourgeois) laws of supply and demand.

The clearest instance of this de-radicalization was in Britain, and underlay the Webbs’ classic definition of a trade union: ‘a continuous association of wage-earners for the purpose of maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment’ (1894: 1). Lenin, as is well known, was greatly influenced by the analysis of the Webbs when constructing his 1902 polemic What is To Be Done? Left to develop spontaneously, he argued, unions would become preoccupied with the defence of their members’ immediate occupational interests. The tendency towards ‘pure-and-simple unionism’ (Nur-Gewerkschaftlerei) – an accommodative and typically sectional economism – could be resisted only through the deliberate intervention of a revolutionary party.

The debates of a century ago became associated with the triple polarization of trade union identities. One model sought to develop unionism as a form of anti-capitalist opposition. This was the goal of a succession of movements of the left: radical social democracy, syndicalism, communism. Despite substantial differences of emphasis – and often bitter internecine conflicts – the common theme of all variants of this model was a priority for militancy and socio-political mobilization. The mission of trade unionism, in this configuration, was to advance class interests.

A second model evolved in part as a rival to the first, in part as a mutation from it: trade unionism as a vehicle for social integration. Its first systematic articulation was at the end of the nineteenth century as an expression of social catholicism, which counterposed a functionalist and organicist vision of society to the socialist conception of class antagonism. On this ideological basis emerged in many countries a division between socialist-oriented unions and anti-socialist confessional rivals. Ironically, however, social-democratic unionism typically assumed many of the orientations of the latter, as social democracy itself shifted – explicitly or implicitly – from the goal of revolutionary transformation to that of evolutionary reform. Already in 1897 the Webbs (who were Fabian socialists) had called for unions to become agencies for the gradual democratization of industry; and across Europe, such a programme was increasingly attractive to union leaders who still proclaimed their socialist credentials but were anxious to legitimate their differences from critics on the left. Concurrently, many christian unionists adopted perspectives which were critical of capitalism, arguing that ‘industry ... should have as its aim not private profit, but social needs’ (Lorwin, 1929: 587). Despite their organizational confrontation, then, social-democratic and christian-democratic unionisms came to share significant common ideological attributes: a priority for gradual improvement in social welfare and social cohesion, and hence a self-image as representatives of social interests.

A third model, not always clearly demarcated in practice from the second – partly because its ideological foundations have more often been implicit than explicit – is business unionism. Most forcefully articulated in the USA, but with variants in most English-speaking countries, this may be viewed as the self-conscious pursuit of economism. Its central theme is the priority of collective bargaining. Trade unions are primarily organizations for the representation of occupational interests, a function which is subverted if their operation is subordinated to broader socio-political projects: hence they must eschew political entanglements. The clearest articulation of a business union ideology is in Perlman’s Theory of the Labor Movement (1928), where he condemned the interventions of both revolutionary and reformist socialists as obstacles to the ‘maturity of a trade union “mentality”’ founded upon workers’ need for collective control of employment opportunities. Analogous arguments can be found, however, in the efforts of many continental European trade unions to assert their autonomy from the socialist parties which had engendered them; or in the sometimes tense relationship between British unions and the Labour Party, in which a strict demarcation between ‘politics’ and ‘industrial relations’ was often jealously asserted on both sides of the divide. The British notion of ‘free collective bargaining’ and the German concept of Tarifautonomie both imply that there should be at most an arm’s-length relationship between the sphere of party politics and that of trade union action.

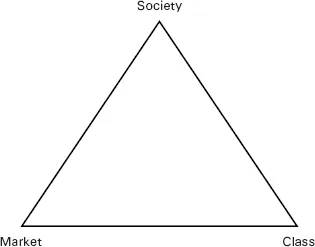

Traditionally, the ideologically-rooted confrontation of competing models of trade unionism has possessed a self-sustaining dynamic. Each model, embodied in substantial organizations with inherited traditions, principles and modes of operation, has acquired over time a considerable institutional inertia. Yet in many respects, the historically embattled ideologies of trade unionism may be regarded as variants on a single theme: a triple tension at the heart of union identity and purpose. The eternal triangle (see Figure 1.1).

All trade unions face in three directions. As associations of employees, they have a central concern to regulate the wage–labour relationship: the work they perform and the payment they receive. Unions cannot ignore the market. But as organizations of workers, unions embody in addition a conception of collective interests and collective identity which divides workers from employers. Whether or not they endorse an ideology of class division and class opposition, unions cannot escape a role as agencies of class. Yet unions also exist and function within a social framework which they may aspire to change but which constrains their current choices. Survival necessitates coexistence with other institutions and other constellations of interest (even those to which certain unions may proclaim immutable antagonism). Unions are part of society.

FIGURE 1.1 The geometry of trade unionism

In one sense, each point in the eternal triangle connects with a distinctive model of trade unionism. Business unions focus on the market; integrative unions on society; radical-oppositional unions on class. Yet a body resting on a single point is unstable. Pure business unionism has rarely, if ever, existed; even if primary attention is devoted to the labour market, unions cannot altogether neglect the broader social and political context of market relations. This is particularly evident when labour market conditions become adverse, when employers no longer agree to reciprocate in orderly collective bargaining, or when hitherto secure occupational groups find their customary position eroded. Unions as vehicles of social integration sustain a rationale for their existence as autonomous institutions only to the extent that their identities and actions reflect the fact that their members, as subordinate employees, have distinctive economic interests which can clash with those of other sections of society. Those unions which embrace an ideology of class opposition must nevertheless (as indicated above) reach at least a tacit accommodation within the existing social order; and must also reflect the fact that their members normally expect their short-term economic interests to be adequately represented.

Hence in practice, union identities and ideologies are normally located within the triangle. All three models typically have some purchase; but in most cases, actually existing unions have tended to incline towards an often contradictory admixture of two of the three ideal types. In other words, they have been oriented to one side of the triangle: between class and market; between market and society; between society and class. These orientations reflect both material circumstances and ideological traditions. In times of change and challenge for union movements, a reorientation can occur: with the third, hitherto largely neglected, dimension in the geometry of trade unionism perhaps exerting greater influence. This is indeed a major explanation of the dynamic character of trade union identities and ideologies.

In the chapters which follow I explore this evolutionary dynamic, first by examining across a broad spectrum of national experience the ways in which market, class and society have informed trade union identity and practice; then by offering a stylized account of recent developments in three countries: Britain, Germany and Italy. In each case – and in international experience more generally – growing instability in the triangular relationship has generated major challenges for unions, while perhaps also opening new opportunities.

Note

1 If this seems too strong an interpretation of the term ‘two sides’ one may refer to the Greek vocabulary of industrial relations; while the term ‘social partners’ has become popular in some circles, ‘the trade unions and their supporters reject or avoid the term, and prefer to use κοινωνικοί ανταγωνιοτέζ (social antagonists) or κοινωυικοί αντίτταλοι (social adversaries)’ (Kravaritou, 1994: 132–3).

![]()

2

Trade Unions as Economic Actors

Regulating the Labour Market

In most English-speaking countries, trade unions have traditionally been viewed as organizations the primary purpose of which is to secure economic benefits for their members; in particular, by advancing their ‘terms and conditions of employment’ through collective bargaining. From such a perspective, broader social and political objectives are of dubious legitimacy, or at best ancillary to unions’ economic functions.

In this chapter I discuss the classic analysis of trade union functions presented by Sidney and Beatrice Webb over a century ago, and the doctrine of ‘business unionism’ which acquired particular force in the USA. In the latter model, industrial relations is perceived as a largely self-contained field of action. Unions succeed best, it is assumed, by their skill and determination in playing the labour market; other forms of union action do not facilitate, and may detract from, unions’ economic goals.

Yet it is questionable how far the labour market can be treated as analogous to the general model of commodity markets; and likewise it is misleading to abstract market processes in general from the socio-political environment in which they are located. Accordingly, there is a contradiction at the heart of business unionism: trade unions can intervene effectively in regulating the labour market only to the extent that their aims and actions transcend the purely economic.

The Webbs: Beyond the ‘Higgling of the Market’

‘A Trade Union, as we understand the term, is a continuous association of wage-earners for the purpose of maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment’: so ran the famous opening by Sidney and Beatrice Webb (1894: 1) to their history of British trade unionism.1 In their subsequent ‘scientific analysis’ (Webb and Webb, 1897) they presented the core function of unions as counteracting the vulnerability of the individual worker in negotiating a labour contract with an employer who was, in turn, obliged by product market competition to cut wage costs while intensifying the pressure of work. Through the principle of the ‘common rule’, unions sought above all else to establish minimum standards in employment and hence to insulate the labour market from cut-throat competition.

The Webbs conceived trade unions as agents of a progressive revolution in industrial relations, a transformation from market anarchy and employer despotism to social control and regulation: hence the title of their major interpretative work, Industrial Democracy. In their reading, the earliest unions – exclusive societies of skilled craft workers – strove to control the market through the ‘device of restriction of numbers’. They fought to defend a specific job territory, excluding outsiders from practising the trade and limiting entry by constraining the number of apprentices. If successful, this ensured an artificial scarcity of their specific category of labour so that the ‘higgling of the market’ operated in their favour. In the long run, however, the Webbs saw this form of trade unionism as futile, since it gave employers a potent incentive to bypass union regulation and to set up with non-union labour.

Hence their insistence on the superiority of the ‘device of the common rule’ which defined standard rates of pay, normal working hours and basic health and safety requirements without otherwise interfering with the individual contract between workers and employers. The common rule could itself be determined by any of three routes which they termed the methods of mutual insurance, collective bargaining and legal enactment. The first was the prerogative of unions with generous ‘friendly benefits’: the common rule was in this case unilaterally defined (usually on the basis of customary standards) and members who were unable to find employment on acceptable terms were supported by an out-of-work ‘donation’ from union funds. (The Webbs were, of course, writing before the introduction of an insurance-based state system of benefits for sickness, retirement or unemployment.) By its nature, mutual insurance presupposed relatively high union subscriptions and a labour market in which all but a small proportion of members could find work on union conditions; in effect it was a method available only to craft societies, and even for these it was unsuitable in times of market turbulence or rapid technological change.

The method of collective bargaining did not suffer from these limitations. The term, originally invented by Beatrice Webb (then Beatrice Potter) in her 1891 study of the cooperative movement, was not explicitly defined by the Webbs in their analysis2 but denoted an institutionalized negotiating relationship between trade unions and employers (or their associations). The advantage of t...