![]()

Part One

Introducing Ida Lupino, Director and Feminist Auteur

Ida Lupino’s consistent thematic preoccupations with the oppressiveness of gender roles; her searing critique of American social institutions in the context of postwar society and American consumerism; and her courage, ingenuity, and powers of professional and artistic negotiation constitute an important story of feminist authorship that has not been fully articulated by scholars and critics. In our reading of Lupino’s life, her acting, writing, producing, and her directing not only of films but also television, we hope to give Lupino a more prominent place in American (and European) film history, one she richly deserves. We begin Ida Lupino, Director: Her Art and Resilience in Times of Transition with a brief biography that discusses her writing, contemporary accounts of her work, and her legacy as a media trailblazer, one who deftly changed careers in mid-life and faced challenges related to her gender as a powerful woman in Hollywood. Throughout Part One, we contextualize this account of her thoughts about her career and the themes with which she was occupied as a woman and a filmmaker. We describe the postwar Hollywood film industry and the rise of independent production linked with a new American realism and “message pictures,” of which The Filmakers, Lupino’s independent production company, was a part. In the concluding section of Part One, we present a close-up on Outrage, a transitional film among Lupino’s early works inflected by Italian neorealism and German Expressionism, a blend of film noir in its examination of the failure of the American Dream and the social problem film. In Part Two, we concentrate more fully on the influence of the social problem genre and film noir in Lupino’s early films.

Given Ida Lupino’s unusual life and versatile career in film and television from the 1930s through the 1970s, it is not surprising that she grew restless with her celebrated acting career and strove to undertake new artistic projects. In the late 1940s, Lupino began to concentrate on independent film production and became a director, writer, and producer. This book explores her groundbreaking work to establish The Filmakers, which she co-founded with writer Malvin Wald and producer Collier Young,1 and her subsequent creative work behind the scenes in film and television.

Like many women before and after her, from Mary Pickford in the early years of film to Jodie Foster and Angelina Jolie, among others, today, Lupino turned to directing after having established herself as an actress. Because of her success in acting and insider status in Hollywood, she was able to smooth the way for her production work, marshaling talent for The Filmakers; writing and directing the company’s films on controversial topics (including unwed motherhood, rape, and bigamy); and disarming the Production Code Administration censors.

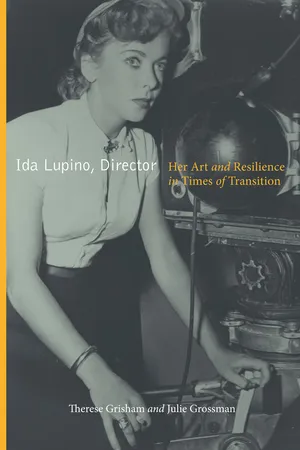

FIGURE 1 Malvin Wald, Ida Lupino, and Collier Young: The Filmakers (The Malvin Wald Collection, Brooklyn College of New York)

The cards were stacked against her, with only one woman before her, Dorothy Arzner, who made her final film in 1943, having directed sound films in Hollywood. Lupino then became the only woman to direct films in Hollywood in the immediate postwar era. While her acting career gave her some power and influence as a filmmaker, her gender certainly made her an outsider. In the next section, we discuss the strategies Lupino employed to succeed in Hollywood. Given the obstacles her outsiderdom posed, it is worth considering at the outset some of the reasons why Lupino took on such a challenge. What motivated her to decide to work behind the scenes?

A Rejection of Hollywood

Lupino had long felt ambivalent about being an actress. Her frustration with Hollywood can be seen early on in her career. In 1942, a Warner Bros. press release quotes Lupino saying that she was “tired of acting”—this, at the ripe age of twenty-four (“Ida Wants to Be Herself”). Fatigued by the pressures of performance that extended to her life off the screen, Lupino commented that actors are “expected to act all the time.” “I don’t want to smile all the time,” she said. “I may want to sit glumly in a corner. After all, you can’t act your life away” (“Ida Wants to Be Herself”).

It wasn’t just the limelight that bothered Lupino. It was her acute sense of the superficiality of life in front of the camera in a setting that objectified actors for profit, notwithstanding Emily Carman's revisionary consideration of the entrepreneurial independent female talent in classic Hollywood. In that same press release, Lupino comments on her “battle to untype [herself].” She remarks on the irony that she was cast as an “ingénue” when she first came to Hollywood in 1933, managing to escape being typecast for dramatic roles, only to wage “the battle all over again in reverse” a few years later as she sought a chance to play comic roles. Worn out by the folie of Hollywood, she said in 1942 that she would “prefer the producing and writing end of [her profession]. At this stage, I would like a long vacation to study and to write” (“Ida Wants to Be Herself”).

Such thoughtfulness went along with a penchant for resisting studio claims on her acting and led eventually to her pursuit of filmmaking. But throughout her acting career, Lupino was ambivalent toward her role as performer and found the studio system unfulfilling, despite her success in transforming herself from nymphet to a fine dramatic actress by the end of the 1930s. In 1943, Hollywood columnist Hedda Hopper wrote that Lupino’s “introspection . . . made an actress out of a blonde playgirl” (“Leap of Lupino”).

Hopper took a particular interest in Lupino’s ambition to alter her status as a glamorous star. In 1949, just as Lupino was establishing The Filmakers, the columnist applauded Lupino’s courage in abandoning her studio contract with Paramount and the $1,750 per week salary she was paid. Hopper recalled acting with Lupino in Artists and Models (1939) and discussing Lupino’s struggle to maintain a sense of artistic integrity inside the studio mill: “I told her,” said Hopper, “‘If you want to be an actress, throw your contract in the ash can and wait for the good parts. If you go on playing these blonde tramps for another year, you’ll lose all that time and maybe the courage to battle for something better’” (“Ida’s Ideals”). Years later, in 1965, Lupino expressed gratitude to Hopper for her encouragement,2 and reflected on her decision, after her successes with films such as They Drive by Night (1940) and The Hard Way (1943), to refuse a lucrative studio deal when Warners offered her a seven-year contract. Lupino recalled, “I said I’d have to think that over. All I could think of was that seven years from that day, I’d be a movie star, but they’d be saying the same thing to another girl that in seven years she’d be another Ida Lupino. I decided there was something more for me in life other than being a big star. So I said no and walked out” (“Walk Back Rocky Road”).

From early on, in other words, Lupino was aware of the commodification of the female star, a theme that would resonate in her work throughout her career. If she took charge in the 1930s to transform herself from a Hollywood baby doll with platinum blonde hair and sculpted eyebrows into a respected actress, she spent the rest of her career pursuing further creative opportunities, rejecting her objectification as part of the Hollywood spectacle. In fact, Hollywood became one of the grinding social institutions Lupino consistently criticized, since she knew well (as she said in 1949) that “Hollywood careers are perishable commodities” (“Lupino Legend”) and sought to avoid such a fate for herself.

With a contract from Paramount awaiting her in Hollywood, fifteen-year-old Lupino emigrated from England with her mother in 1933; her father stayed in England to work and to take care of her sister Rita, who would later emigrate to the United States. Lupino grew up feeling pressured to become an actress, given that her father, Stanley Lupino, was a well-known stage comedian who was himself the heir to a legacy of performing Lupinos going back centuries (see Bubbeo 155). “I did what I thought would make my father proud of me,” she said in an interview in 1976. “I knew it would break his heart if I didn’t go into the business” (Galligan 10). She first stepped onto the stage for an audience at the age of seven, despite her aversion to performing. Interviewed by Morton Moss for the Los Angeles Herald Examiner in 1972, Lupino recalls, “I was the only one who didn’t want to be part of it. I’d hide in the closet to avoid being forced to act. It was like pulling all your wisdom teeth. It was absolute, stark terror. That feeling never changed. . . . I was scared into being an actress, shoveled into it.”

Lupino’s initial film appearance was in England, in Allan Dwan’s 1932 Her First Affaire, in which, at the age of fourteen, she played a seductive teenager who falls for an older, married writer. A short time afterward, she appeared with her godfather, matinee idol Ivor Novello, in a film in which she played his lover. The episode reveals much about Lupino’s childhood: “So, there I was,” she remembers in 1976,“. . . lying on a couch on top of my Godfather playing an eighteen-year-old hooker, saying: ‘O my Gawd, ducks, I’m mad about you—I’ve got to have you’” (Galligan 10).

While Lupino still lived in England, Paramount Studios noticed her in a film called Money for Speed (1933). A small part of the film features her playing a sweet girl, on the basis of which Paramount brought her to Hollywood to star in Alice in Wonderland. When Lupino appeared at the studio in 1933 to read for the part of Alice, one of the executives commented that she sounded more like Mae West than Lewis Carroll’s Victorian girl. Thus Lupino’s career in Hollywood was stalled from the beginning because of her family’s push for her to grow up at a very young age.

If the precocious Lupino was unsuited to play Alice, her roles as seductive young women were equally a mismatch, given Lupino’s intellect. She was bored and insulted by the roles she was offered, culminating in 1934 in her suspension from Paramount after refusing a part in Cleopatra: “I was supposed to stand behind Claudette Colbert and wave a big palm frond. I said, ‘No thanks’” (“Walk Back Rocky Road”). Spending the rest of the decade acting in insignificant films and doing radio work to supplement her income, Lupino received her big break in 1939 with The Light That Failed, adapted from Rudyard Kipling’s novel about a blind painter whose working relationship with a destitute Cockney model named Bessie drives the model to madness. During the casting period, Lupino aggressively lobbied William Wellman, the film’s director, to let her audition. He hired her on the spot after her impassioned impromptu reading of the part of Bessie Broke. Lupino earned rave reviews for her performance and, after another quiet period—“back into oblivion” in Lupino’s words—she was asked by Warners to test for Raoul Walsh’s They Drive by Night (1940). Lupino once again stole the film with a bravura performance that included going mad (“The doors made me do it. Yes, the doors made me do it!”). After the success of her collaboration with Walsh at Warner Bros., she was offered the seven-year contract that she would soon refuse.

Lupino Directs

Lupino resisted acting from the start because she found it to be too focused on spectacle and appearance. Even as a teenager in Hollywood, she rejected the film industry’s commodification of talent, and soon began to search for a creative life away from the spotlight. She took a risky path by refusing Warners’ lucrative contract in the 1940s, but she did so in order to choose her own roles, both on and off the screen. It is also worth noting that Lupino’s childhood, during which she was thrust into mature and adult settings at a very early age, would inform the stories about lost innocence and the exploitation of youth she was drawn to throughout her filmmaking career.

Just as the stories she helped realize on the screen are rooted in Lupino’s understanding of marginalization and alienation, her directing work is deeply attuned to the psychic experience of space and place. Her “poor bewildered people” (Lupino, qtd. in Parker 22) drift across a postwar American landscape where their isolation is distinctly connected to the social and gender roles Lupino saw as hostile to individual desire. Lupino’s own role in Hollywood as an insider (an acclaimed actress) and outsider (a woman filmmaker) gave her a unique perspective on the theme of isolation, on the challenges her own creative force as a woman would pose to the status quo, and on the projects she undertook. Hollywood was only one of the modern social institutions she rebuffed. While throughout her life Lupino was eager to learn, her ambivalence toward formal education stemmed in part from her unhappy experiences in boarding school as a young child. As her daughter Bridget recalled, “She seemed to think school was a lot of suffering. She didn’t feel like a duck in water with academia. She already had that artist’s spirit” (“Ida Lupino: Through the Lens”). In her films, Lupino was especially critical of marriage, which she saw as failing those who entered into its contract, mainly because of the scripted roles it demanded that men and women play. These roles were disappointingly backward-looking in light of the modernity World War II was supposed to have ushered in, if we think of that modernity as a loosening of gender roles and the offer of more equitable gender relations. The government promulgated these roles in part by recruiting women to work in many different jobs and careers, as well as by encouraging women to stay single, even giving them communal housing, during the war. Postwar modernity was really a retrograde version of those gender roles and relations, a step backward.

In a radio interview with Anna Roosevelt in 1949 prior to the release of Not Wanted, Lupino spoke about the cultural habit of making pariahs of individuals who violate social norms: “Life doesn’t give us the means of finding love within the bounds of our conventions and many of us will find it outside.” Lupino here makes a plea for extending sympathy to unwed mothers and their children, rejecting, as Anna and her mother Eleanor Roosevelt did, not only the practice of “pointing the finger of blame at the girl or her family or any individual,” but the prejudice implied in the rhetoric of “illegitimate children.” Lupino’s desire in Not Wanted to show “the heartbreak of the unwed mother” and the “difficulties of life, such as poverty, ignorance, overwork [that] are the underlying causes of girls becoming mothers outside of marriage” reflects her commitment to social change and her belief in the power of film to help bring about that change.

Lupino’s work reveals modern institutional life, as it regulates personal and professional opportunities, to be oppressive, exploitative, and ultimately absurd. Her deep suspicion of cultural authority figures links her to Fritz Lang, Orson Welles, Nicholas Ray, Roberto Rossellini, and Alfred Hitchcock. Like these modernist filmmakers, Lupino sees human agency as often futile and desire as usually thwarted. In addition, like the celebrated male filmmakers who present us with the grand failures of their characters’ strivings, Lupino’s tone is ironic, repeatedly demonstrating the gap between desire and reality. Because Hollywood offered a particularly salient example of the failure of the American Dream for Lupino, it was a setting Lupino rejected, m...