![]()

Chapter 1

The Artificial Birth

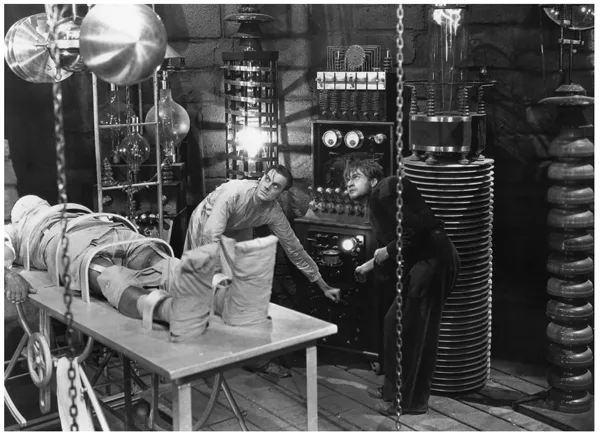

Perhaps the best-known story about a constructed or artificial person in modern literature, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818) offers an evocative depiction of the animation of Victor Frankenstein’s monster.1 The creature is formed as a man about eight feet in height, assembled in Victor’s workshop from body parts stolen from cadavers, and animated through a process that is both scientific and mysterious, potentially combining alchemical and electrical means. In contrast to its treatment in film, where it has acquired dials, vials, bubbling liquids, strange machinery, hunched assistants, and the power of lightning, in the novel the description of the monster’s animation is evasive and remarkably brief. Victor recounts: “It was on a dreary night of November, that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils. With an anxiety that almost amounted to agony, I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet. It was already one in the morning; the rain pattered dismally against the panes, and my candle was nearly burnt out, when, by the glimmer of the half-extinguished light, I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs” (37).

The novel’s version of animation contains many of the elements that we find again and again in stories of artificial people: they are born adult, through processes that do not require sexuality, in contexts that often do not include women or family. The moment of animation includes at least one visible event that marks the radical change of status for spectators, in this case the opening of the eye and the convulsion that alerts Victor of the monster’s aliveness. These visible markers structure the scene’s before/after format and render it supremely suited for later spectacular treatments in cinema.2 Everything that usually takes place inside the body is externalized: processes of conception and gestation are transformed into visible and instantaneous events, and the pain and mystery of childbirth are replaced by technological promises of clarity and control—promises betrayed rather quickly in Frankenstein but still operative in other texts of the discourse.

While it may seem inevitable that a historical account of artificial people should begin with Frankenstein, the text functions as both origin and limit. Although Frankenstein is justifiably heralded as foundational for modern science fiction, the conceptual patterns of the monster’s animation are not unique to Frankenstein.3 Despite its technological trappings, the representation of the artificial birth is in fact rooted in a transhistorical conceptual vocabulary: Shelley’s depiction of animation is consistent with an array of premodern animating scenes found in origin stories and cosmological myths, in literary texts that reference ancient ritual patterns, and in medieval and early Renaissance scientific and pseudo-scientific fantasies. Even elements we take for granted or experience as thoroughly modern, such as the focus on visibility, emerge in animating tales of great antiquity. This paradoxical dimension of the discourse of the artificial person is my topic in this chapter, which focuses on the multiple ways in which issues of origin structure stories of artificial people. Far from inspiring questions of influence or imitation, the transhistorical consistency of animating scenes becomes the basis for a more theoretical understanding of the stakes of the animating story, in premodern and modern contexts.

Taking the iconography of the artificial birth as a point of departure, this chapter proposes that to understand the origins of the discourse of the artificial person, to see “where artificial people come from,” we might focus on how they are born. Indeed to say they are born is itself provocative or paradoxical: the fact that artificial people are usually not born is one of the most fascinating things about them. Yet even as their mode of construction couldn’t be further from childbirth, this sense of conceptual distance—of two scenes that couldn’t be further from each other—also signals a formal relationship. Stories of artificial people traffic in the reversal, negation, or transformation of bodily states, and primary among them is the negation of childhood. Although they are often depicted as proverbial children, new to the world, artificial people almost never appear as babies, and very rarely inhabit a child’s body. From ancient tales of the creation of Pandora and Galatea to the ritualistic animation of the Golem in the Jewish Kabbalah, to the sexy physicality of the Replicants in Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982), and the striking technological birth scenes of Ghost in the Shell (Mamoru Oshii, 1995), part of the appeal of artificial people seems to depend on the attractions of their adult bodies, bodies usually gendered and rendered in culturally specific ways in terms of race, ethnicity, age, and physical appearance.

Artificial bodies are also compartmentalized, either because they are made of stitched-together body parts (as with Victor’s creature), or because they have no body fluids (as is the case with robots in later stories), or because their construction involves radically different interior and exterior materials, as with the metal skeleton and artificial skin of the cybernetic beings in The Terminator (James Cameron, 1984). Even the distinction made in Victor’s workshop between the material body, the “lifeless thing” awaiting its animation, and the “spark of being” that will infuse it with life speaks to this compartmentalizing tendency and registers the discursive importance of dualist notions of body and soul, body and mind, or matter and spark for this story type. Yet despite these negations, artificial people cannot escape the burden of their embodiment: their appearance and physicality function deterministically, since it is often these features that mark artificial people as other, with tragic consequences in the creature’s case. And while the artificial birth is often described as a cerebral process, as a construction or fabrication, it is in fact intimately related to processes of human generation.

The structural consistency of artificial birth fantasies offers an eloquent identification of what matters in the discourse of the artificial person. My contention is that when we ask “where do artificial people come from?” we are, and perhaps unconsciously, exactly at the crux, the linchpin of the issue. Artificial people emerge from the contexts that evolve around a similar question, asked since the beginning of human civilization: “where do people come from?” Origin stories, or stories that attempt to answer or radically expand this question, can be our guide to the relationship between real and artificial people before the modern era, when the boundary between them operates within different conceptual rubrics. My analysis begins from the middle of things, from a closer look at Frankenstein and the novel’s inclusion of both premodern and modern conceptualizations of matter and animation, before moving on to ancient, medieval, and early modern versions of the artificial birth. Although the styles and means, visual effects, and scientific explanations may vary, the question of the beginning of life is never uncomplicated. Recognizing the transcendental roots of the artificial birth can help us explain why the narrative of animation later becomes so pervasive in technological, political, and existential contexts.

On Birth and Death: Rereading Frankenstein

No other text in the discourse of the artificial person enjoys the cultural position of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The novel’s inspiration and writing are the stuff of legend, its impact dispersed and immeasurable. And it is perhaps both fitting and profound that a story about a being born fully formed, without parents, without peers, and without descendants, would be so concerned with questions of origin and progeny, that it would exert so much influence on later literary, scientific, and cinematic culture, and that it would inspire such speculation about its origins as a text.

Contemporary scholars generally agree that the two main versions of Frankenstein present two distinct approaches to science and ethics, and this bifurcation affects how we understand the artificial birth in the novel.4 The original 1818 novel presents Victor’s work as an unconventional but rational scientific project and does not judge or interpret his actions for readers. Although, as Marilyn Butler has argued, Shelley intends a subtle critique of Victor’s loosely vitalist ideas, the novel’s ambivalence masks its irreverence, allowing audiences to understand Victor as naïve, misguided, or obsessed, without rendering him or his pursuits particularly impious.5 We owe the more stereotypical approach to the novel as a cautionary tale against hubristic overreaching scientists to Shelley’s revisions for the 1831 edition. Some of her changes aimed to reframe the representation of science: while references to magnetism, electricity, and polar exploration were not controversial in 1818, by 1831 a series of public debates about radical science, vitalism, evolution, and genetics inflected the public’s view of Victor’s scientific aspirations.6 Eager to legitimize the novel and keenly aware of the public’s interest in her own tumultuous life, Shelley adds a moralistic tone in the 1831 edition, as Victor expresses regret, alludes to uncontrollable evil forces taking over his work and life, and frames his research as a form of hubris. In Shelley’s new preface, Victor’s work in natural philosophy becomes an engagement with the “unhallowed arts” (190), while her textual revisions target Victor’s motivations and reactions, both in constructing the creature and in rejecting him. Indeed in the most clearly preemptive gesture of the 1831 preface, Shelley explains away the fundamental mystery of her novel, presenting Victor’s panicked recoil from his creation as a moral and religious given. “Frightful must it be,” she explains, “for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (190). By thus reestablishing divine and moral order, Shelley attempts to dispel the emotional and psychological chaos of the animating scene, instead presenting the novel as an expression of the desire for and failure of imitation. And Victor’s symptom finds a name: hubris, pride, overreaching, solipsism, scientific obsession, moral blindness, the desire to become godlike, the unholy aspiration to understand or control what only the divine controls.

Returning to the 1818 version of the novel without such preconceptions, one finds a more dynamic range of meanings. The text does not actually explain why Victor panics when the monster comes to life, and it certainly does not interpret his revulsion as a sudden return to Christian piety. Instead, Victor’s shock transforms the monster’s animation into a traumatic parent/child scene, unparalleled in modern literature for the intensity with which it depicts the drama of narcissistic projection, and the trauma of withdrawal, rejection, and alienation. The monster, initially addressed as “it” during the animation scene and as “he” by the next paragraph, is curiously not recognizable as a human form, even though we are told that all his body parts were deemed beautiful when selected. Challenging essentialist notions of identity and disrupting both aesthetic and ontological chains of being, the monster embodies the unreadable, the unspeakable.7 Far from feeling victorious, Victor experiences revulsion, a reaction that is all the more powerful for being so immediate and irrevocable. “How can I describe my emotions at this catastrophe, or how delineate the wretch whom with such infinite pains and care I had endeavoured to form?” he asks (37). Victor recoils, collapses, and then flees. As the novel unfolds, the former skeptic and scientist who had claimed early in the novel that he was immune to supernatural terrors will soon become a man terrified of shadows and sounds.

Despite its scientific trappings, the animating scene in fact performs a substitution of mysteries: while the creature’s animation promises to reveal the order of nature, in the transformation of inanimate matter into a living being, his rejection evokes mysteries that are closer to home. Instead of presenting a unique sublime event, Frankenstein doubles the animating scene, creating a sequence in which the monster’s body comes to life literally through Victor’s technological processes, only to be de-animated symbolically and socially by his rejection. Combining the explanatory power of an origin story and the traumatic power of a primal scene, this treatment of animation also switches focus from science to emotion, and from the outside to the inside, and allows for multiple emotional perspectives. Readers may inhabit the position of the scientist faced with the ineffable, the parent faced with a child’s wondrous or threatening otherness, the abandoned or rejected child, and the fascinated observer whose eavesdropping on the family drama is anticipated in the novel in the character of Robert Walton, the polar explorer listening to Victor’s story. In the dynamic melodrama of identity facilitated in the scene, the reader may be defending or policing the human but also seeking to be included in the human fold or feeling unjustly excluded. And while Victor’s motivation remains unclear, the monster’s pathos is all too familiar. Despite the violence the monster unleashes in the course of the novel, his perspective is thereafter understandable, informed not so much by how he is made but by how he is unmade by processes of familial, social, and political rejection.

While the novel displays a philosophical pastiche of poetic, scientific, and social thought, much as the monster presents a collection of disparate body parts, there is a multivalent coherence of form in this unusual book. As if in narrative emulation of the questions of the inside and outside that motivate this story type, the novel’s formal structure presents a series of framed narratives: in letters to his sister, North Pole explorer Robert Walton writes of his meeting with Victor, reporting Victor’s narration of his tragedies, embedded in which we find the monster’s own story and experiences, which include the narratives of the De Lacey family and Safie’s tale.8 This box structure itself deploys a symbolic register in which the problems of exteriority and interiority, of material form and “spark of being,” play out in the novel’s composition, tempting us to look for an ever more interior story within the framed narratives or instructing us to notice the intra-frame connections. The novel offers numerous motifs that intersect within these nested narratives: orphans, idealized women, angelic but dead mothers, difficult or cruel parents, sailing, the North, ice, mountains, the desire for a friend, the desire for open travel to the ends of the earth, the desire for a quiet hearth amid the cold. A focus on passages and transitions can be found in the amniotic calm of Victor’s many reveries sailing on various lakes, Walton’s failed search for the fabled North Passage, and the novel’s final chase scenes on a sea of ice. The novel in effect teaches us to read for both matter and spark: if the framed narratives offer the body parts, the materials, the matter of our encounter with the book, we find a different trajectory in the through-lines, repetitions, and serial returns among the frames. This dynamic trajectory moves across or through the framed narratives and engages readers in a significatory quest that animates the story beyond its basic content.

One of these through-lines affects how we understand the animating process in the book as a whole. Adding to the dispersed emphasis on passages, the novel does not treat the body as inert matter that comes to life with the addition of a soul—indeed the soul is not an animating agent but a record of experience for the creature and is used in relation to his character only twice in the 1818 edition. The first mention occurs when the creature entreats Victor to listen to his story: “Believe me, Frankenstein, I was benevolent; my soul glowed with love and humanity” (73). Later, when Victor reaches the end of his own narrative, he warns Walton about the monster’s character: “His soul is as hellish as his form, full of treachery and fiend-like malice” (165). It is only after the monster’s many murders that his soul, once pure and loving, matches his already hideous form. In the 1831 edition Shelley adds a trap, a misdirection that again enables a more Christian and classically dualist reading of the text. In this version, after the death of Clerval, when Victor returns to Geneva with his father in order to kill the creature he asserts: “I might, with unfailing aim, put an end to the existence of the monstrous Image which I had endued with the mockery of a soul still more monstrous” (207). In this doubly retroactive move, Victor misremembers the animating process, where a “soul” did not pertain as either concept or scientific entity, and Shelley misrepresents the novel, destabilizing the material relationship between body and spark that motivates the book.

In contrast to the top-down structure implied by the soul-added-to-body rubric (a conventional description for such scenes), the animations of the novel in the 1818 version do not depict a controlling soul or a single localized life source, instead favoring dispersed or pervasive animating agents, life forces that may be added and subtracted, or that fluctuate radically, but that exist throughout the body. This subtly materialist treatment of animation—and also of inspiration, vitality, and liveliness—infuses the text with a series of animations and de-animations, enacting a tendency toward circularity that adds an alchemical element to the novel’s otherwise modern depictions. The animating language that permeates the novel reveals Shelley’s skillful manipulation of linguistic referent, with words first appearing in their everyday or metaphorical sense and then reappearing as technical terms or as potentially scientific literalizations of a gothic reality. Victor, for exampl...