![]()

Part I

Playing Fields

The Social Landscape of Youth Sports

![]()

Chapter 1

Surveying Youth Sports in America

What We Know and What It Means for Public Policy

Don Sabo and Philip Veliz

Former NBA basketball player and New Jersey senator Bill Bradley liked to quip that “the most popular sport in America is jumping to conclusions.” In the United States, adults often approach youth sport from a polarized, “all bad” or “all good” perspective (Eitzen 2003). Coaches are lauded or vilified. Competition is good or bad for kids. Sport enhances kids’ health or endangers it. Sport provides kids from different races, socioeconomic backgrounds, and genders an opportunity to get ahead in life or it re-creates social inequalities. But the reality is that members of the general public and research communities have only a modicum of facts and analyses to inform their assessments of youth sport. In this chapter we draw from survey research to shed light on the role of sport in kids’ lives, while pointing to new puzzles that can be explored with future research.

Sport sociology has grown since its inception during the 1970s, and yet, as Michael Messner and Michela Musto observed in their introduction, comparatively few sociologists focus on youth sports. This chapter provides an overview of what survey research reveals about US kids and sport. First, we describe participation patterns in competitive organized youth sports, focusing on variations by gender, race, and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, grade level, family characteristics, and type of community. Second, we summarize recent national data that confirm that children leave organized sports in droves as they age—a pattern that is especially prevalent among girls and kids of color. In this regard, we point to the decline in the number of US public and private schools—especially those schools with higher proportions of girls and racial/ethnic minorities—that provide interscholastic sports to their students. Third, we evaluate research on the links between youth athletic participation and educational achievement across all sport. Fourth, we examine research on links between athletic participation and adolescent health, such as illicit drug and alcohol use, physical activity involvement, sexual risk taking, and pregnancy prevention. Finally, we identify emerging areas in which sport survey research is needed, such as children with special needs, poor kids, children in immigrant families, and GLBT youth.

Participation: Who and How Many?

Social scientists recognize that millions of American youth play sports, and that youth sports have grown tremendously, particularly since the passage of Title IX in 1972 (Stevenson 2007). Less is known about why children get involved, stay involved, play multiple sports, quit one sport to explore another, leave sport altogether, or never play sports in the first place. Even fewer studies have considered how or why schools and communities provide differing levels of participation opportunities to young people. Are girls, kids from poor or working-class families, or racial and ethnic minorities provided the same level of opportunities as boys, well-to-do kids, and whites? Does youth sport function as an “equal opportunity” sector in America, or does it reflect (and maybe reproduce) inequalities between rich and poor, whites and minorities, boys and girls?

Counting the number of kids involved with sports is an important but daunting task. Sports governing bodies, coaches, educators, child and teen health advocates, parent-teacher organizations, and public health providers use overall participation rates and subgroup comparisons to guide policy and action. Social scientists who use survey research to study youth sports have tapped large government-sponsored databases to assess participation patterns and trends.1 Some data sets measure athletic participation in general, meaning they ask teenagers how many sports they participated in during the past year in their school and community. Some government school-based surveys gather information about involvement with specific sports like basketball, cheer, football, lacrosse, swimming, or volleyball (Johnston et al. 2014). Although data gathered from government surveys are often nationally representative, and have sophisticated sampling designs and high response rates, not all school officials comply. The effort to clearly understand complex realities involving millions of kids remains a work in progress.

Despite these flaws in the data, it is clear that lots of kids play sports. In collaboration with the Women’s Sports Foundation, during 2007 we conducted two nationwide surveys of kids and parents in order to better understand intersections among families, schools, and communities, and US children’s involvement with sport. We commissioned the Harris Interactive to conduct a school-based survey of youth from a random selection of about one hundred thousand public, private, and parochial schools in the United States. The final sample consisted of 2,185 third through twelfth grade girls and boys. We also conducted phone interviews with a national cross-section of 863 randomly selected parents of children in grades three through twelve. African American and Hispanic parents were oversampled in order to enhance understanding of the needs and experiences of underserved girls, boys, and their families. We outline some key findings from this Go Out and Play survey later (Sabo and Veliz 2008).

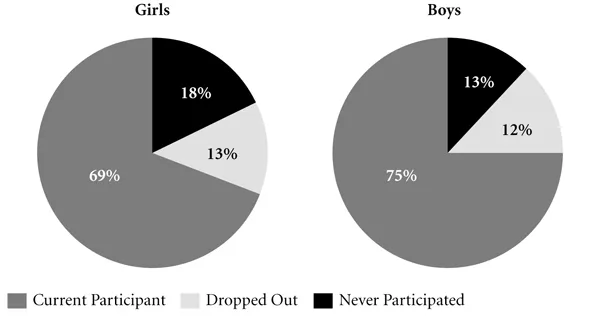

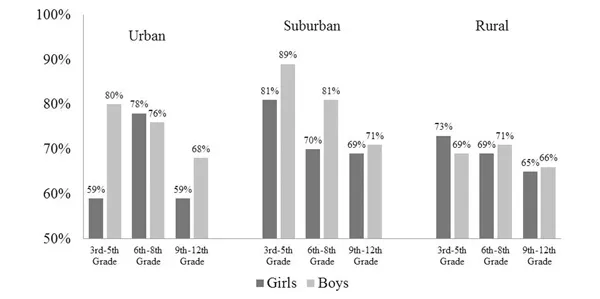

Nearly three-quarters of youth reported playing an organized or team sport, while fully 84 percent were currently playing or were past participants when asked. Only 15 percent said they have never participated in a sport. As figure 1.1 shows, nearly equal percentages of girls and boys reported currently playing organized and team sports (69 percent and 75 percent, respectively). Just 18 percent of girls and 13 percent of boys reported never participating in a sport at all, and high percentages of US children were involved with at least one sport across all grade levels. Participation rates varied a great deal, however, by grade level and type of community. Figure 1.2 demonstrates that when considering students involved with at least one sport, for example, participation was most prevalent among suburban elementary school students and also among children in urban middle schools. And yet, in urban communities, only 59 percent of third to fifth grade girls were involved with sports, compared to 80 percent of boys. The widest participation gap, between ninth through twelfth grade girls and boys, also occurred in urban communities (59 percent and 68 percent). Furthermore, despite the fact that large percentages of children participate in sport at some point in their lives, girls enter sports at a later age than boys (7.4 years old, on average, compared to 6.8 years old), and this gender gap is widest in urban communities (girls 7.8 and boys 6.9 years old).

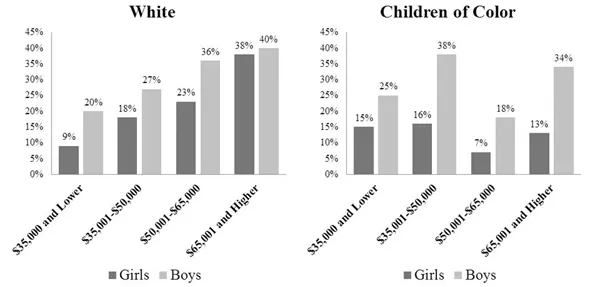

Economic disparities and racial inequalities often mediate gender gaps in sport. High involvement with sports was more typical if kids came from wealthier, more affluent communities. Overall, kids from richer communities were more apt to play three or more sports. And yet the results in figure 1.3 reveal that for both white girls and white boys the percentages of highly involved athletes grew as family median income increased. In contrast, among children of color, boys outnumbered girls as highly involved athletes across all the income groups. For girls of color, the percentages of highly involved female athletes declined in the upper-middle and well-to-do income categories ($50,000–65,000 and above $65,000). In short, a rough gender equity exists for highly involved white girl and boy athletes from the above-$65,000 income group, yet girls of color from all income levels showed lower rates of participation in US youth sports than their male counterparts.

Gender, race, and class also influence kids’ drop-out rates. Girls and boys tend to leave sport at increasing rates as they move from elementary school to high school. Suburban girls, however, are the one exception to this trend—their drop-out rate remains steady at 6 percent from third through eighth grades. Whereas the drop-out rates of suburban and rural girls and boys in middle schools were comparable, the rate for urban girls in middle schools was four times higher than that for suburban girls (24 percent and 6 percent) and twice as high as for rural girls (13 percent).

The findings raise important questions about girls’ experiences with sport. Why, for example, do so many urban girls leave sport during the middle school years? A three-year program evaluation study conducted by the Boston Girls Sports and Physical Activity Project sheds light on this issue (Women’s Sports Foundation 2007). Urban communities often provide more athletic opportunities to third through fifth grade boys than girls, which means that for many girls it is not until middle school (sixth–eighth grades) that they have real options to get involved with sport. As a result, urban girls are more likely than boys to start sport during middle school. The Boston evaluation revealed that because of the comparatively later start, many urban girls did not develop the physical literacy or athletic skills as boys their age. Girls’ fewer athletic options translated into a lack of athletic self-confidence, less fun, and feeling clumsy and out of place. Finally, some urban girls who tried sports but quit during middle school did so because they were needed at home after school to care for siblings while their single parents worked. Boys weren’t expected to fill these child care roles.

The Go Out and Play telephone survey with parents also generated information about youth sports and family life. For example, we found that children’s involvement with sports was associated with higher levels of family satisfaction. Youth sports helped build communication and trust between many parents and children. Sports provided a vehicle for parents and kids to spend time together, to have conversations, or to practice together, both in dual-parent families and single-parent families. While a majority of parents said they want similar levels of athletic opportunity for their daughters and sons, 39 percent of moms and 37 percent of dads believed that their community offered more sports programs for boys than for girls. Moreover, 32 percent of white parents felt this way, compared to 51 percent and 49 percent of Black and Hispanic parents, respectively. And finally, 53 percent of low-income parents shared this perception, compared to just 31 percent of high-income parents. Furthermore, while mothers and fathers provided similar levels of encouragement and support for both their daughters and sons, girls were often shortchanged by dads, who seemed to channel more energy into mentoring sons. While many fathers endorsed “fairness” and equal support for girls as well as boys, results from the student survey showed that whereas 46 percent of boys ranked dads as number one on their list of mentors who “taught them the most” about sports and exercise, dads ranked third on girls’ list, coming in at 28 percent. Mothers ranked fifth at 23 percent.

Michael Messner’s (2009) and Tom Farrey’s (2008) respective books on youth sports have helped fill the “sport and family” research void, but there clearly remains a great deal to learn about the role of youth sports in families. In the Go Out and Play study (Sabo and Veliz 2008) we suggested that sports often act as “part of a wider convoy of social support” (7) that may bring children into closer contact and communication with their parents. However, more nuanced qualitative studies of specific sports in a variety of community settings and interviews with parents who represent the range of parental involvement in youth sport are sorely needed. Just as there is no such thing as the “American family,” there is no typical or overarching template surrounding family life and youth sport involvement. The challenge for researchers is to better understand the complex processes that surround youth sport and family life.

Attrition: Kids’ Movements In, Out, and Between Sports

The range of athletic options has grown in recent decades. Gone are the “old days” when boys’ football, basketball, baseball, and track and field were the only games in town. Previous thinking around kids’ participation in sport was often simplistic—kids either “played” or “dropped out” of sport. However, the “in and out” dichotomy tells only part of a more complex story of youths’ participation in sport. Later in the chapter we discuss a recent survey that documents some of the complexity that enables kids’ movements in, out, and between various sports (Sabo and Veliz 2014a).

Monitoring the Future (MTF) provides perhaps the richest trove of data on teen athletic participation in a variety of sports (Johnston et al. 2014). About fifty thousand students are surveyed every year (eighth-, tenth-, and twelfth-graders) and pertinent information is gathered pertaining to sports participation as well as educational outcomes, health behaviors, social engagement, and substance use. The large sample sizes and troves of information enable researchers to examine participation rates among eighth grade, tenth grade, and twelfth grade students in a variety of sports.2 Since 2006, respondents have been able to specify baseball, basketball, cross-country, field hockey, football, gymnastics, ice hockey, lacrosse, soccer, swimming, tennis, track and field, volleyball, weight lifting, wrestling, and “other sports.” We believe that the “other sports” category provides a general vehicle to capture participation...