![]()

1

In a Country of Eternal Light

Frankenstein’s Intellectual History

Everywhere science is enriched by unscientific methods and unscientific results, . . . the separation of science and non-science is not only artificial but also detrimental to the advancement of knowledge. If we want to understand nature, if we want to master our physical surroundings, then we must use all ideas, all methods, and not just a small selection of them.

—Paul K. Feyerabend, Against Method

Commentators traditionally regard Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus as the most influential cautionary tale ever written. To this day, it remains a compelling illustration of how the seductive temptations offered by scientific research can drive researchers both to reckless excesses and a blatant disregard for ethical limitations. Such a black-and-white reading, however, fails to account for the spectrum of scientific investigation embraced and condemned by the novel. A more nuanced and historically contextual view articulates the ways in which Frankenstein walks the line trodden by many earlier scientists who struggled to defend and more clearly define their profession, thereby providing the foundation for contemporary research practices. Reviewing the variety of natural philosophies forwarded by the Renaissance authors at whose feet Shelley lays Victor’s corruption provides insight into how the rich entanglements of magic, theology, and natural philosophy function in the novel, establishes the ethical boundaries that shape the scientific revolution and its later adherents, and forms the framework for our modern conceptions of legitimate research aspirations and experimental protocols.

Frankenstein aggressively attacks the path advocated by many Renaissance magi who believed that the study of the natural world necessarily led to an understanding of the divine plan within nature and, consequently, to their control over it. While rejecting Renaissance natural philosophy, Shelley simultaneously embraces a very different kind of scientific investigation, one that places her work squarely in the middle of the ongoing struggles to define “science” in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Her approach to knowledge production, especially chemistry and polar exploration, ultimately develops a definition of the kind of science championed by many at the dawn of the nineteenth century. Controlled, occurring within institutions and the confines of peer review, and deliberately within the realm of the visible and the natural, this kind of science provided a greater understanding of the world people inhabited and illustrates how they believed science could help them to better control that world. The new approach to scientific information depended on codes of gentlemanly conduct and the ties binding scientific men to produce a culture of peer review and an emphasis on method, replicability, and witnessing that made honor among men an integral part of scientific culture and that features prominently in the binding relationship between Robert Walton and Victor Frankenstein in the novel.

Juxtaposed to the tenets of Renaissance natural philosophy, Shelley provides readers with three crucial litmus tests for separating “good” from “dangerous” science that reflect the scientific culture that spawned Frankenstein. Several windows provide readers access to the types of science and sources the novel deems legitimate and helpful versus those categorized as dangerous and potentially harmful. For example, science within the context of the university or, in the case of Arctic exploration, with governmental and institutional support emerges as beneficial, especially when it occurs in a peer-governed environment that maintains boundaries that distinguish acceptable and desirable endeavors from dangerous and harmful projects. Isolated investigations, on the other hand, veer into dangerous territory and can encourage scientists to indulge their egos and desires for personal power rather than to gain knowledge for the greater good. Motive is another defining factor for damning or lauding specific scientific endeavors. Tightly articulated efforts to better understand a specific aspect of the natural world or, in the case of exploration, to locate new sources of desirable materials or potential trade routes are suitable intellectual work. Conversely, grandiose projects that aim to eliminate all disease or solve the mystery of life remain inherently problematic and demonstrate the practitioner’s hubris, as well as a risky failure to grasp the collaborative nature of scientific work. Finally, the novel approves of work that seeks to better understand the way objects function within the natural world, but it rejects elaborate projects that endeavor to attain power over other objects or systems within nature as overreaching and potentially destructive.

As a result, Frankenstein calls into question the scientific context its period inherited, juxtaposing the opposing ideas and concerns that shaped the world of late eighteenth-century and early nineteenth-century scientific investigation. The science it champions is closely tied to the formal rules for experimentation established and enforced during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries by institutions such as the Royal Society in England, the Académie Royale in France, and major European universities. Such approaches to scientific explorations were also embraced by the men who embarked upon expeditions to better understand the biology and anthropology of exotic locations, such as the Arctic, the Antarctic, and the tropics. Because their governments often subsidized these voyages, the knowledge gained—and any new property discovered—belonged to the states that sponsored them. This arrangement meant that the process of gaining knowledge was subject to the ethical standards adopted—or at least publicly held—by their governments, and the explorers necessarily represented those regimes during their travels.

Offshoots of the Royal Society developed to provide peer review for this kind of natural science as well, including the Royal Geographical Society. Efforts to publicize the findings of natural scientists, often packaged for public consumption to stress the moral compass of the lead investigator and his selfless devotion to knowledge production, provided significant public access to—and widespread support for—natural science and scientific expeditions. Shelley’s novel falls into an interesting place within this arena because it provides two examples of scientists whose labors flirt with disaster. It damns Victor for his grandiose ambitions and refusal to join the scientific enterprise of his era and saves Walton from his personal quest for glory with a stern reminder about his social status and responsibilities to the men who serve him. Shelley also delivers a severe reminder to Walton about his socioeconomic place in society and his responsibility to the English nation.

But the actual emergence of this scientific culture is far less clear-cut than the gentlemen of the Royal Society would have wished—or publicly admitted. A review of their transcripts reveals a shared space between what we would recognize as science and early modern pursuits of natural knowledge that reflect the sixteenth century better than the nineteenth. For example, the expeditions undertaken by early nineteenth-century explorers and natural scientists in search of the open polar sea, especially in the face of extensive evidence supporting its nonexistence, are as steeped in the English imagination as any alchemical quest. The difference lies in the framing integral to understanding both the science of this period and the scientific vision in Frankenstein. Embraced by members of the Royal Society and the Royal Navy as a means of extending the power of the English nation—through both the gathering of new natural knowledge and the potential discovery of a highly lucrative and useful trade route—the investigation of the Arctic was separated from the myths still permeating the English vision of the region and embedded in the realm of useful and meaningful scientific investigation.

Part of the transition from imagined geography to formal scientific exploration involved making exploration a governmental project and, as a subsidiary goal, a viable means of employing the Royal Navy in the military vacuum following the Napoleonic wars. Such a shift separated gentlemen scientists devoted to the discovery of natural knowledge for the sake of the nation from benighted dreamers, like Shelley’s Robert Walton, bent on pursuing personal greatness through the realization of their Arctic-twilight fantasies of Hyperboreans and earthly paradise. This project was not unique to the nineteenth century. Steven Shapin writes at length about the importance of gentlemanly status in determining the worth of scientific observation in seventeenth-century England; various scholars clearly demonstrate how the shared roles of personal observation—with the value of that observation depending to some extent on the social role occupied by the observer—and historical authority merge in sixteenth-century European natural philosophy.1 But an urgency characterizes these late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century iterations, emerging at least in part because of the increasing institutionalization of science and its practitioners’ need to legitimize the discipline by differentiating between worthy and unworthy practice.

In Frankenstein, both Victor and Robert Walton derive their scientific imaginations from historical sources, and many literary critics characterize their failed quests as an overt rejection of the Romantic imagination, particularly its hyperbolic language and grandiose gestures. Shelley does, indeed, chastise both men for their actions in the novel; she places the malformed Creature squarely at the feet of the ambitious Victor, who inherits his ideas from natural philosophers such as Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa and his peers, and reproves Walton for his near-fatal search for unknown places and undiscovered people inspired by his childhood reading of exploration tales. But Shelley’s attitudes—given the sources she credits for seducing Victor away from the legitimate pursuit of knowledge—are also a rejection of the Renaissance magi who hoped to gain knowledge of the natural world. Such a goal was inspired by a desire to better understand, and even mimic, God, a narcissistic quest doomed to failure and set against natural and religious prohibitions.

Walton, Natural Science, and the Contest over Authority

Victor Frankenstein’s scientific enterprise has attracted meaningful scholarly attention during the last thirty years, much of which contributes to our understanding of how this novel reflects research currents within late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century English science. Samuel Vasbinder, for example, states, “All of Victor’s scientific studies can be traced in eighteenth-century science. There is not a statement made by [Shelley] that does not have at least one, sometimes dozens, of echoes in the scientific literature of her age.”2 That literature included a slew of theories attempting to explain how energy moved in the body—and how this activity related to sickness and health and to life itself. Mesmerism and galvanism attacked the first two of these, while the ongoing debates at the Royal College of Surgeons between 1814 and 1816 about how life begins and the interest in what constituted the “spark of life” concentrated on the third. The proliferation of these themes in Frankenstein demonstrates that Shelley was very familiar with the principal scientific questions of her day. Her careful delineation of scientific education under the watchful eyes of professors within the university community establishes that she also understood the ways in which scientific knowledge was produced, both legitimately and illegitimately, according to the conventions of her age.

The novel favors a particular approach to scientific work and explicitly supports certain kinds of investigations, most notably those grounded specifically in the natural world and not delving too deeply into loftier questions about how life begins, the unifying power behind all living things, and whether that power could be replicated. As such, Frankenstein can easily be read as a warning to scientific experimenters inclined to seek the glory promised by solving the great mystery of life. That said, however, a more subtle reading that champions a stricter version of science is also plausible. In addition to warning readers to avoid the problems of what constitutes life and how it begins, Shelley also condemns the misguided, solipsistic approach Victor adopts. The novel presents the treacherous pitfalls of working in isolation, thereby detached from communal advice and, if necessary, collegial intervention. Instead, Shelley suggests that researchers function most productively when operating under the watchful eyes of their peers, rather than removed from society in a laboratory with only their egos to judge their progress and guide their decisions. In this sense, then, Frankenstein reflects the emergence of a clearly defined scientific community that maintained its own rules for producing and assessing natural knowledge.

The perspective regarding scientific research that Shelley presents in the novel was not unique to the early nineteenth century. The Royal Society, for example, was awarded its first charter in 1662, in which King Charles II granted its members access to unclaimed bodies to pursue anatomical investigations, among other natural philosophical queries, along with the land and buildings necessary to house a great institution. This charter also recognized the importance of an international scientific community when he granted its members the right to “enjoy mutual intelligence and knowledge with all and all manner of strangers and foreigners . . . in matters of things philosophical, mathematical, or mechanical.”3 Similar institutions formed across Europe during the seventeenth century, including the Accademia dei Lincei in Rome in 1603 and the Académie Royale in Paris in 1666 (formally incorporated and chartered by the king in 1699).4 The rise of these institutions, which provided a place to discuss and pass judgment on scientific questions and approaches, increasingly brought natural philosophy into the purview of a knowledge community. The participation of the government in these institutions was matched by various European monarchs’ interest in what their kingdoms could gain from science. By investing in exploration, for example, all of the major European governments pinned their hopes for gold, new transport routes, and other treasures on the coats of scientists whose goals were often very different. When the Royal Navy and the Royal Society undertook quests for the open polar sea, for example, they had different goals for the missions they funded, but they shared the commitment to exploration as an integral part of nation- and knowledge-building.

Take, as an example of Shelley’s viewpoint, Walton’s naval quest for an open polar sea as a manifestation of the intersections between widely known scientific events and Frankenstein. England approved the renewed quest for that polar chimera in 1818, the year Shelley’s novel was first published. Yet the importance of the social communities governing and contributing to scientific knowledge production and the relationships and their helpers remained a vexed question, especially in the ice-choked waters of the polar seas, where experienced seamen were frequently endangered by library-trained experts with minimal (or no) practical knowledge. In retrospect, the learned scientific men who refused to accept the expertise of sailors, whalers, and even less formally educated but more practically experienced men defined nineteenth-century English Arctic exploration. In choosing people to embark upon major, crown-funded expeditions, for instance, the Royal Navy regularly granted expert status to educated men of higher social class over those with practical experience, even if they came with an acknowledged reputation for expertise in natural science. This preferential treatment favored men whose theories about the Arctic ran parallel to the Admiralty’s own, rather than those with prior experience in the region.

The contest over the relative authority of eyewitness testimony and classical texts, such as Pliny, has its roots in the Renaissance, and thus its appearance in a novel whose scientific framework owes a great debt to that period is not coincidental. Walton, Frankenstein’s final friend, is exactly the kind of man whose social class and lack of formal experience should have attracted Royal Navy funding, but he fails to gain a place on a national expedition because he lacks a formal education. Even so, his social class still guarantees him some consideration, while whalers and other uneducated but highly experienced men were rejected outright. William Scoresby, for example, was a veteran whaler and acknowledged expert in natural science who achieved international scientific recognition for his seventeen years of observations and drawings of polar ice. Yet he was refused a place on the government-sponsored and Royal Society–backed Arctic expedition in 1818 for two reasons: first, he lacked an Oxbridge education, and second, he took the opposite view of Sir John Barrow, the second secretary of the Admiralty and the director of polar expeditions, about whether an open polar sea was likely, contending that its absence from the reports of whalers, fishermen, and expert sea captains proved that it did not exist.5

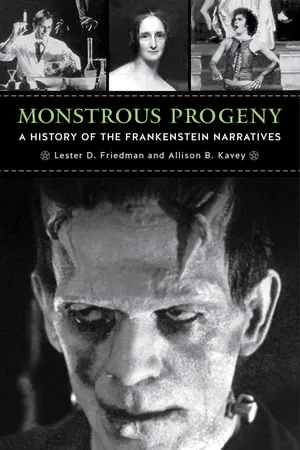

This image of the icy waters of the summer Arctic as observed during one of the expeditions to find the Northwest Passage was published in a very popular book about the expedition.

Presented as a real thing in ancient books once accepted without question as authoritative, the existence of an open polar sea was increasingly being questioned because no individual had witnessed it. Its foothold in the English imagination of the Arctic notwithstanding, the open polar sea was under attack in Shelley’s time, and the fact that Walton saw a frozen wasteland, not a tropical paradise and open water, and a gigantic creature whose existence had only been verified by its creator puts his testimony on shaky ground.. The reiteration of scientific procedure as central to confirming old tales and making new knowledge underscores the importance of the emerging scientific method in Shelley’s model for research investigations. The struggle to determine whether the experience of many individuals was more relevant than the theories contained in aged tomes went on for centuries, ultimately becoming foundational to the creation of the modern scientific approach accepted as legitimate today.

The transition from accepting single authoritative ancient reports to trusting only multiple testimonies by different witnesses to determine an experiment’s or object’s legitimacy took a long time. Its ascendency owes much to the oversight of institutions such as the universities and the Royal Society, both of which stressed the value of peer-reviewed k...