![]()

1

The Silent Screen, 1895–1927

Mark Lynn Anderson

The notion of a motion picture “producer” was initially a default identity for manufacturers of early motion picture equipment, such as Thomas Edison and Siegmund Lubin, once they began making films on a semi-regular basis at the turn of the twentieth century. It was also a label used for popular artists and entertainers like J. Stuart Blackton and William Selig, who supplied the early theatrical and itinerant markets with motion pictures. These inventors and showmen would eventually found the first movie studios in the United States, as well as form the industry’s first significant trade organization at the end of 1908, the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC).

In many ways, these early producers (inventors, showmen, cinematographic operators who screened short actualities) were the first recognizable motion picture personalities. During this period, the motion picture producer performed various types of work that would quickly become separate vocations in an emerging division of labor and in cinema’s legibility for a fascinated public. Early producers might typically write scenarios, scout locations, procure costumes and properties, direct and edit films, process prints, write promotion, secure sales, ship prints, or even project motion pictures in large exhibition venues, all of this in addition to attending to budgets and the legal and financial concerns of the companies they operated. Furthermore, their very names became the brands that created product differentiation for exhibitors and the public alike.

Movie Workers

The day-to-day work of the studio executive has been documented in various studies of the film industry and in the researched biographies of the more celebrated producers. However, the producer’s job was also regularly represented in popular and educational literature, sources that can tell us much about the public’s understanding of the industry and its appreciation of management’s role. The creation and evolution of the film producer as a public figure has received little attention from historians of the industry, even among those who have sought to reveal the “real workings” of the studio system behind the myths. Many of the popular myths about Hollywood were just as much products of the industry as were its films and movie stars. Still, such depictions can tell us a lot about how the film producer came to be recognized as a specialized worker within the studio system by an interested audience.

In 1939, Alice V. Kelijer, Franz Hess, Marion LeBron, and Rudolf Modley wrote a slim book entitled Movie Workers in which they endeavored to explain the division of studio labor to school-age children. They described the work of the film producer in relation to that of the director:

The producer and director are the ones who are responsible for all of the details of a movie production. The producer is the general manager. He takes care of the business, the purchasing, the advertising, the distribution, and the supervision of all departments working on the picture. The director is responsible for the making of the picture itself. He directs the actors, plans the camera work, guides the lighting, and is on the set to supervise all shooting of the movie. After a story is chosen for production the producer and director have story conferences to decide about details of changes and ways of screening the story.1

While the book’s authors describe the contributions of the various studio departments to motion picture production, they significantly position the producer and the director as ultimately “responsible for all the details,” with the director portrayed as the chief creative talent and the producer the principal managerial authority. This represents the ideal of the central producer system that was gradually introduced and refined during the late 1910s and 1920s.

Because the Hollywood studios became vertically integrated during the same period, the producer depicted in Movie Workers is also responsible for advertising and distribution. Here the producer is imagined as an executive with broad authority over the entirety of a studio’s operations, rather than as either an associate producer to whom an executive producer might delegate some of his own specific duties or as what we would now recognize as a unit manager who coordinates the talent and resources on a single production by implementing a predetermined work schedule.2 The executive producer oversees the studio’s full schedule of ongoing productions, as well as the distribution and promotion of all the firm’s products. In this way, the executive producer is the agent of industrial organization whose vision is not divorced from the creative basis of motion picture art but forms the very possibility of that art’s realization as entertainment for the masses. While the director might occupy the more romantically conceived position of an individual artist, the producer is more or less the personification of the studio as a unique business enterprise, one that is committed to a cultural mission of advancing and fulfilling the aesthetic aspirations of a moviegoing public.

Such a distinction between director and producer did not always exist. Consider this description of film production at the fictional Comet Film Company from Laura Lee Hope’s 1914 juvenile novel, The Moving Picture Girls at Rocky Ranch.

The scene in the studio of the moving picture concern was a lively one. Men were moving about whole “rooms”—or, at least they appeared as such on film. Others were setting various parts of the stage, electricians were adjusting powerful lights, cameras were being set up on their tripods, and operators were at the handles, grinding away, for several plays were being made at once.3

The author describes a bustling studio with a fairly advanced division of labor and with the various departments at work on several productions at once, a depiction of the “dream factory” that would become a routine representation of Hollywood filmmaking at the height of the studio system. However, none of the productions at the Comet Film Company have individual directors assigned to them. Instead, all these motion pictures are coordinated by a Mr. Pertell who, “once he had all the various scenes going[,] took a moment to rest, for he was a very busy man.”4 In the novel, Pertell is the ostensible owner of the film company, as well as its coordinating manager, and he personally directs the filming of the more elaborate feature productions, leaving individual camera operators to shoot the more conventional program fare.

Hope depicts camera operators as unit directors. In doing so, she describes a craft situation more indicative of the earliest days of American film manufacture, when, before 1907, as the film historian Janet Staiger notes, “the cameraman knew the entire work process, and conception and execution of the product were unified.”5 Hope’s fictional account thus represents a blurring of early social and technical divisions of labor in the evolving film industry.

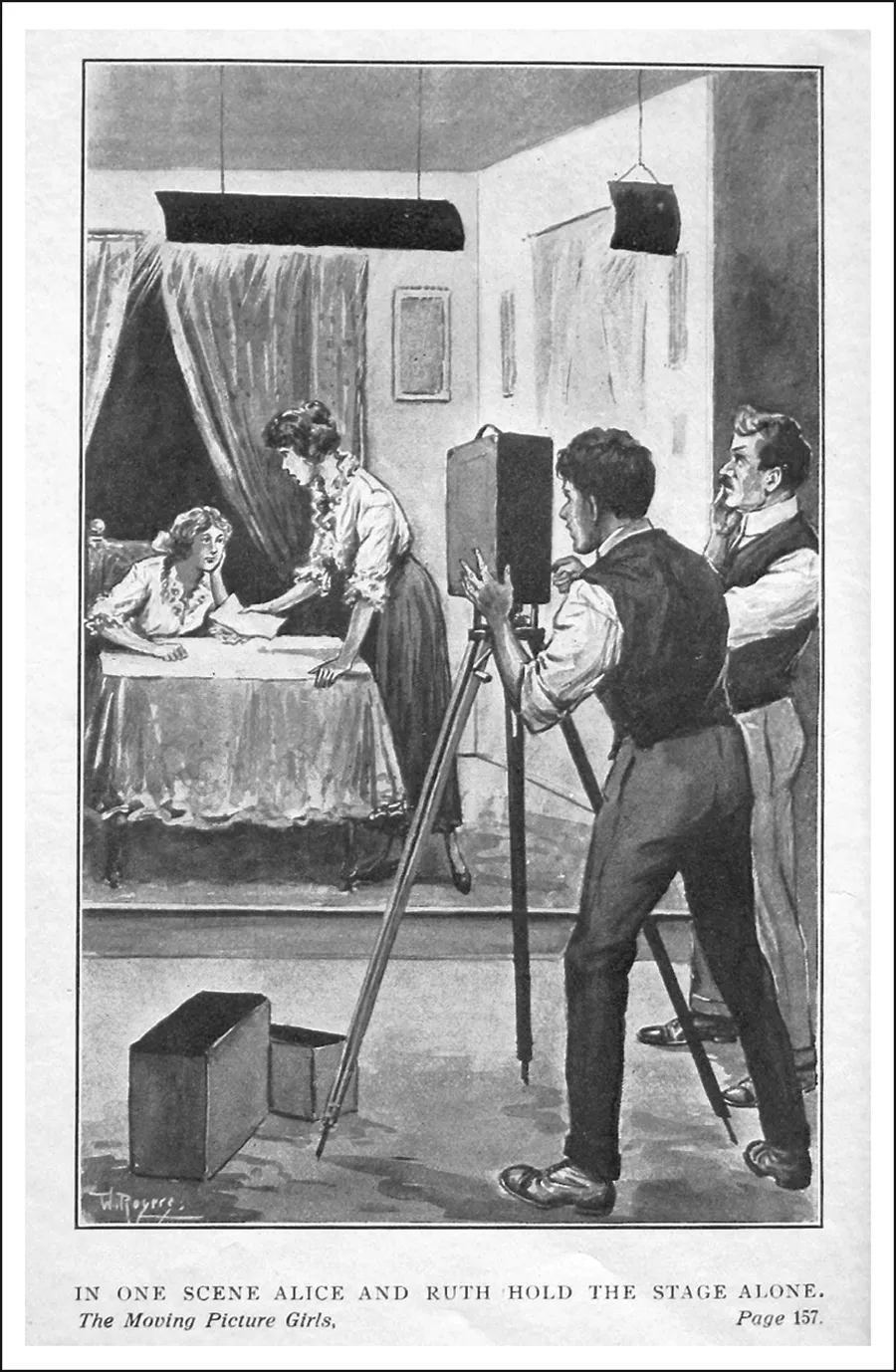

FIGURE 4: In Walter S. Rogers’s illustration for Laura Lee Hope’s The Moving Picture Girls at Rocky Ranch (1914), we can see that both Mr. Pertell, the studio manager, and cameraman Russ Dalwood are familiar with “the entire work process” at the Comet Film Company.

In Hope’s series of seven novels featuring the Moving Picture Girls, written between 1914 and 1916, these operator/directors are subject to a central coordinating authority of a producer/manager, a production context more indicative of the increasing technical division of labor that emerged after the director’s task had been firmly distinguished from the camera operator’s and a director-unit system was implemented during the late nickelodeon era (in the early to mid-1910s).6 Yet, in the Moving Picture Girls series, the camera operator’s broad manufacturing expertise is repeatedly demonstrated. On those occasions when the company’s youthful cameraman, Russ Dalwood, explains various aspects of film production to the novels’ central characters—the two DeVere sisters who act for the company, as well as to the novels’ young readers—these distinct albeit somewhat overlapping historical production models are combined. Through such means Hope is able to preserve the impression of studio manufacture as essentially a cottage industry, despite its increase in scale as the studios sought to exploit a mass entertainment market.

This notion of a filmmaking enterprise that preserves the family and familial relations within its ever increasing division of labor casts the producer/owner/manager in the role of a wise and watchful patriarch whose business success, which often results from outwitting unscrupulous competitors or from effectively adjudicating disputes between company employees, is the index of both his creativity and his fatherly beneficence. In Hope’s novels Mr. Pertell is “a very busy man,” indeed. This notion of the producer as a visionary protector of the family would become part of the enduring mythos of American film history, most easily recognizable in the silent period by those popular monikers of “Uncle Carl” (Laemmle) and “Papa” (Adolph) Zukor given to the chief executives of Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Famous Players–Lasky, respectively.

Producing and Public Relations

The increasing refinement of the role of the producer in the early studios was driven by market forces that promoted increasing motion picture output to service the expanding demand from exhibitors and exchanges for fresh product. By the 1910s, the industry’s ability to build and maintain an exploitable audience for motion pictures required the transformation of the experience of cinema: from viewing films as attractions on a mixed vaudeville bill or as a continuous program of short, one- and two-reel motion pictures screened in small, storefront theaters, to attending a sizable theater to see an advertised, multiple-reel motion-picture attraction whose featured player, genre, or subject matter constituted the principal reason for the purchase of a ticket. While managerial duties during the nickelodeon period varied from studio to studio, owners and their managers typically dealt with the oversight of the financial aspects of the business, overseeing accounts, payroll, and sales, while directors and camera operators coordinated and executed most of the preproduction, production, and postproduction processes. Relations between owners, managers, and directors could vary widely during this period, but the work of conceiving of motion pictures and then making them was one of the least formalized parts of the business, with directors and camera operators often pursuing and innovating their own methods and approaches on a day-to-day basis.

The Biograph Company was one of the most fiercely competitive studios of the nickelodeon era in terms of protecting its financial interest. It had successfully fought Edison’s attempt to control the market through licensing agreements by strategically acquiring crucial camera-technology patents in 1908.7 Biograph’s ability to control patents guaranteed the company’s eventual inclusion on its own terms in the MPPC, America’s first film oligopoly. Nevertheless, when D. W. Griffith arrived at the studio in 1908, the production process at Biograph was staggeringly unorganized. Linda Arvidson, the famous director’s spouse, described one aspect of this disorganization, the transient situation of acting talent during their first days at the studio in 1908.

It was a conglomerate mess of people that hung around the studio. Among the flotsam and jetsam appeared a few real actors and actresses. They would work a few days and disappear. They had found a job on the stage again. The better they were the quicker they got out. A motion picture was surely not something to be taken seriously.

Those running the place were not a bit annoyed by the attitude. The thing to do was to drop in at about nine in the morning, hang around awhile, see if there was anything for you, and if not, beat it up town quick, to the agents. If you were engaged in part of a picture and had to see a theatrical agent at eleven and told Mr. McCutcheon so, he would genially say, “That’s O.K. I’ll fix it so you can get off.” You were much more desirable if you made such requests. It meant that theatrical agents were seeking you for the legitimate drama so you must be good!8

While Arvidson seeks to describe a moment before screen acting held any social prestige, suggesting that the low character of film work created the conditions of an unmanaged workplace, she is also describing a moment just prior to the star system in which, because of a lack of standard practices, motion picture production was propping itself on and deferring to a theatrical labor market. Griffith himself, who came from the world of the theater, would shortly change this situation at Biograph when he formed a stock company of players with actors who had ongoing contractual obligations to work at the studio and to act in the company’s films.

Mary Pickford recounts how Griffith, against the concerns of studio management in the spring of 1909, offered her a guaranteed contract at $40 per week against the standard $10 a day she had been earning as a featured player.9 These and similar means of stabilizing the pool of acting talent for motion pictures were simultaneously implemented at other studios, often at the behest of directors who typically scouted and developed screen talent.

In this way, directors and director/producers were defining what would soon be a key task of the movie producer during the silent era and beyond, the contracting of a select group of screen talent whose rising salaries compensated not only for their hours of labor at the studio but also for their value as company assets, in other words, movie stars whose market value was presumably determined by popular demand. This became one of the first and most visible roles of the producer for a public increasingly interested in the working lives of the personalities they observed on the screen.

One of the most retold stories in American film history credits the independent producer Carl Laemmle with inventing the star system when he announced in early 1910 that he had placed Florence Lawrence under contract at his Independent Motion Picture Company (IMP). The promotion of IMP’s acquisition of Lawrence’s contract sought to publicly reveal and bank on the actress’s name. The company at which she had risen to fame, Biograph, had maintained a policy, observed by many studios of the period, of not providing the public with the names of its regular performers. Previously known only as the “Biograph Girl,” at IMP Lawrence was a key part of a publicity campaign in which the studio advertised not its films or its brand name, but its ability to lure a popular performer away from the very company with which she was once so closely identified. According to the film historian Eileen Bowser, an early advertisement for Lawrence’s new position, prior to the revelation of her name, featured only her portrait with the words, “She’s an Imp!”10

While these developments are widely recognized as the basis for what would become the regular promotion of movie stars, they also illustrate how one of the central tasks of the executive producer was defined during this period and how it was intimately tied to the developing star system, that is, the control and crafting of the studio’s public image. Whether the first movie stars appeared because of a public demand to know more about the screen performers they had come to recognize and admire or, conversely, whether the star system was principally an industrial strategy to standardize a product in order to guarantee an exploitable market of regular, recurring consumption, Laemmle’s promotion of Lawrence represents the work of the producer as promoting both the quality of the company’s products and its ability to provide the public with what they wanted and what they deserved at a cost they could afford. Thus, in addition to scheduling and overseeing the production process and managing the division of labor, the producer played a crucial role in public relations—the management of information about the company and the control over how such information is disseminated in order to shape public opinion and consumer habits.

Unlike most of the early manufacturers and inventors who headed the studios of the MPPC, the second wave of producers, such as Laemmle (who had operated nickelodeons in Chicago as early as 1906 and moved to production into 1909) came predominantly from the ranks of motion picture exhibitors and other amusements b...