![]()

Walt Whitman Birthplace, Huntington Station, New York, where the future poet caught his first glimpse of the ordinary plant that would inspire his most extraordinary book: grass.

PHOTO CREDIT: WALT WHITMAN BIRTHPLACE PHOTO COURTESY OF GEORGE MALLIS, PHOTOGRAPHER.

1

Celebrating the Many in One

WALT WHITMAN BIRTHPLACE 246 OLD WALT WHITMAN ROAD, HUNTINGTON STATION, NEW YORK

Humble local materials—wood and stone—were what a Long Island carpenter used to build this simple house for his growing family in the second decade of the 1800s. Some large rocks provided the foundation. Roughly cut whole tree trunks bound together by wooden pegs sat atop the boulders forming the base. The walls, too, were made from hand-hewn logs attached to each other with wooden pegs. It was all covered by a roof of cedar shingles.

The child who was born in this house in 1819 would learn carpentry from his father, Walter Whitman, the man who built it. But young Walt, as he would come to be known, would not be remembered as a builder of houses. Instead, he would serve his readers by becoming a builder (as he put it in the preface to his most famous book) of paths “between reality and their souls.” He would be remembered for teaching Americans how humble local materials—the lives of ordinary people and the world that surrounds them—could be the stuff from which great poetry could be wrought: distinctive, compelling poetry in the American grain that would change his countrymen’s ideas of what American poems (and poets) could be.

The second child of Walter Whitman and Louisa Van Velsor entered the world in the first-floor “borning room.” His father liked the radical political philosophy of Tom Paine, while his mother was attracted to the mystical, democratic ideas of Quaker preacher Elias Hicks. They named several of their other children after presidents—George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson—but it was the child who bore his father’s name who would take his parents’ passion for democracy to new heights.

Walt Whitman lived in this pleasing, airy country farmhouse until he was four years old, when the family moved to Brooklyn. The unusually large windows his father built throughout the house drenched it in more sunlight and fresh air than was customary for houses of its kind in the area. It was through those windows that Walt caught his first glimpse of the world beyond the bedroom in which he was born. It was the world just outside those windows that he would immortalize in poetry some thirty-five years later when he would write, in a poem that would be known as “There Was a Child Went Forth,”

There was a child went forth every day,

And the first object he looked upon and received with wonder or pity or love or dread, that object he became,

And that object became part of him for the day or a certain part of the day . . . or for many years or stretching cycles of years.

The early lilacs became part of this child,

And grass, and white and red morninglories, and white and red clover, and the song of the phoebe-bird,

And the March-born lambs, and the sow’s pink-faint litter, and the mare’s foal, and the cow’s calf, and the noisy brood of the barnyard or by the mire of the pond-side . . . and the fish suspending themselves so curiously below there . . . and the beautiful curious liquid . . . and the water-plants with their graceful flat heads . . . all became a part of him.

And the field-sprouts of April and May became part of him . . . wintergrain sprouts, and those of the light-yellow corn, and of the esculent roots of the garden,

And the appletrees covered with blossoms, and the fruit afterward . . . and woodberries . . . and the commonest weeds by the road; . . .

The lilacs and morning glories that the child saw, the apple trees and wood berries are no more. Only one acre and a barn remain from the sprawling farms and orchards worked by his ancestors in this area since the mid-1700s. But this one acre is enough to remind us of that part of the natural world that inspired Whitman’s most compelling poetic vision—for it is covered in grass from the same soil that nurtured the grass that the poet tumbled in as he was learning to walk, the grass that the child saw when he “went forth” and the grass that he “became” in the poem that would come to be known as “Song of Myself” in the stunning book he published in 1855, titled Leaves of Grass:

A child said, What is the grass? Fetching it to me with full hands;

How could I answer the child? . . . I do not know what it is any more than he.

I guess it must be the flag of my disposition, out of hopeful green stuff woven.

Or I guess it is the handkerchief of the Lord,

A scented gift and remembrancer designedly dropped,

Bearing the owner’s name someway in the corners, that we may see and remark, and say Whose?

Or I guess the grass is itself a child . . . the produced babe of the vegetation.

Or I guess it is a uniform hieroglyphic,

And it means, Sprouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones,

Growing among black folks as among white,

Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressman, Cuff, I give them the same, I receive them the same.

And now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves.

Tenderly will I use you curling grass,

Walt Whitman used that grass not only as the title of his book, but also as an object lesson in how the poetic imagination works. By showing the reader the ways in which the poet’s imagination can transfigure something as common as leaves of grass, Whitman makes good on his promise to share with his reader “the origin of all poems.” This is how you do it, the poet seems to say: look at the grass; really look at the grass; see it and see all that it connects with, all that it resonates with, all that it suggests, all that it sparks in your imagination. And somewhere along that path between the concrete physical world and the world of the spirit, Whitman seems to say, a poem will be born. For the poet, Whitman teaches us, “a leaf of grass is no less than the journey work of the stars.”

Until he wrote Leaves of Grass, Whitman thought poetry came from somewhere else entirely. His earliest poems feature the saccharine, sodden, abstract, and sentimental musings standard in popular graveyard verse, featuring lines such as “But where, O Nature, where shall be the soul’s abiding place?” They were rhymed and trite and eminently forgettable, filled with exotic subjects (a descendent of the royal family of Castile, a young Inca girl), archaic and stilted language (“’tis said,” “o’er,”), and pompous diction (“dark oblivion’s tide”).

But at the same time that he was writing hackneyed poetry, he was writing journalism that was often quite innovative for a series of New York newspapers. For example, the “city walks” to which Whitman treated readers of the New York Aurora, the city’s fourth-largest daily paper, were as fresh and vivid as his attempts at poetry were stale and pale. While an article titled “New York Market” published in the Tribune was typically filled with the prices of cotton and flour, the “Market” piece that appeared in the Aurora was dense with vivid concrete detail. In the Grand Street market he enters, Whitman waxes rhapsodic about the “array of rich, red sirloins, luscious steaks, delicate and tender joints, muttons, livers, and all the long list of various flesh stuffs” that “burst upon our eyes!” And he observes the people—a “journeyman mason . . . and his wife,” “a white faced thin bodied, sickly looking middle aged man,” a “fat, jolly featured” woman who is “keeper of a boarding house for mechanics.” “A heterogeneous mass, indeed, are they who compose the bustling crowd that fills up the passage way. Widows with sons, . . . careful housewives . . . men with the look of a foreign clime; all sorts of sizes, kinds and ages, and descriptions, all wending, and pricing, and examining and purchasing.”

Whitman’s great breakthrough as an artist came when he realized that the same subjects, styles, stances, and strategies that he had explored as a journalist could be central to his project as a poet, as well. The wonder of the “heterogeneous mass” (a variant on the “many in one” theme that would always be so important to him) would be central to all of his greatest poems, reflecting not only the diversity of people who made up the human community, but also the diverse states that joined together to form the United States of America (and whose union was embodied in the nation’s motto, “e pluribus unum”).

In “Song of Myself,” the dazzling autobiographical language experiment Whitman published in 1855, the theme of the “many in one” comes together for him in powerful ways. He celebrates his vision of the “many in one” not only in relation to the human community and the nation, but also in relation to himself. The child who “went forth” from the farmhouse in South Huntington had learned to appreciate the connections between himself and all that was outside him, and had learned to look with awe on the essential puzzle of identity (of oneself, of one’s country, of the universe)—the many in one.

In his preface to the 1855 Leaves of Grass, Whitman provided a job description for the poet he aspired to be:

His spirit responds to his country’s spirit. . . . To him enter the essences of the real things and past and present events—of the enormous diversity of temperature and agriculture and mines—the tribes of red aborigines—the weather-beaten vessels entering new ports or making landings on rocky coasts . . . the union always surrounded by blatherers and always calm and impregnable—the perpetual coming of immigrants—the wharfhem’d cities and superior marine—the unsurveyed interior—the log-houses and clearings . . . the fisheries and whaling and gold-digging . . . the noble character of the young mechanics and of all free American workmen and workwomen . . . the perfect equality of the female with the male . . . the factories and mercantile life and laborsaving machinery—the Yankee swap . . . the southern plantation life—the character of the northeast and of the northwest and southwest—slavery and the tremendous spreading of hands to protect it, and the stern opposition to it which shall never cease till it ceases. . . . For such the expression of the American poet is to be transcendent and new. . . . Let the age and wars of other nations be chanted and their eras and characters be illustrated and that finish the verse. Not so the great psalm of the republic. Here the theme is creative and has vista. . . .

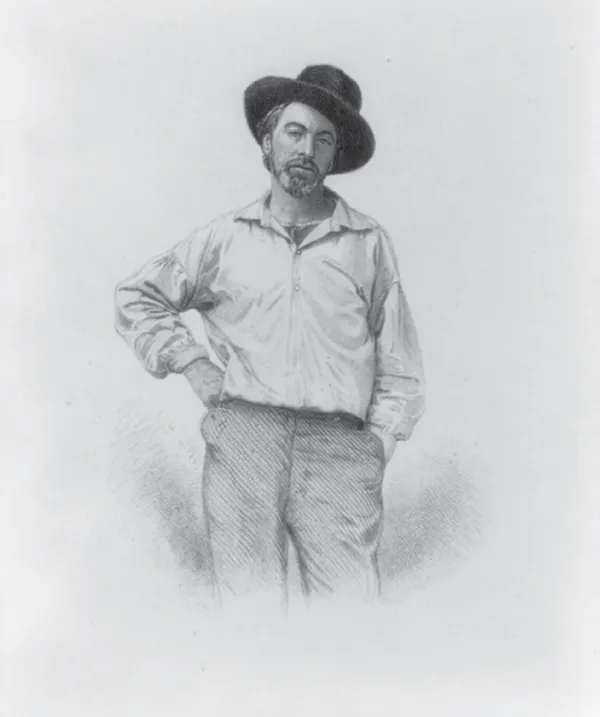

Whitman was urging outright rejection of the very sorts of exotic subjects he himself had once aspired to making poetry out of. “Away with novels, plots and plays of foreign courts,” he would later exhort in “Song of the Exposition”: “I raise a voice for far superber themes for poets and for art, / To exalt the present and the real.” The image of Whitman that stares out at the reader from the volume’s frontispiece conveys a sense of the author as an unpretentious workingman concerned not with the foreign, exotic, or affected, but with “the present and the real” of his own time and place.

Walt Whitman (1819–1892) as he chose to present himself on the frontispiece of the first edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855.

PHOTO CREDIT: COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, PRINTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION, WASHINGTON, DC.

Whitman’s call for a poet very much like himself was not as original as the book of poems he produced; indeed, it distinctly echoed a plea that Ralph Waldo Emerson had made in 1842 in a lecture on poetry that Whitman covered as a New York journalist (Emerson later published the gist of this lecture in his essay “The Poet”). But if this vision of the poet was not without precedent, the poetry Whitman presented to the world certainly was. Upon receiving a copy of Leaves of Grass, Emerson sent Whitman one of the best-known letters in literary history: “I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed. . . . I give you joy of your free and brave thought. . . . I find in...