![]()

1

Simulated Women and the Pygmalion Myth

Men have long been fascinated by the idea of creating a simulated woman that miraculously comes alive, a beautiful facsimile female who is the answer to all their dreams and desires.

The shaping story comes from the myth of Pygmalion as retold by the ancient Roman poet Ovid in The Metamorphoses. Pygmalion, a sculptor, was dismissive of women. He was “dismayed by the numerous defects of character Nature had given the feminine spirit” and pledged to remain chaste and not have any relations with them.1 Instead, he sculpted a beautiful ivory image of a perfect woman, and he fell in love with this simulacra. Ovid tells us that Pygmalion’s artistic creation was superior to a real woman, for he gave his sculpture “a figure better than any living woman could boast of.”2

This sculptural lady in the tale is so lifelike that Pygmalion wonders whether she is a mere statue or alive, and he lovingly adorns her with rings, pearl earrings, and a necklace. In his love and longing, he prays to Venus to give him a woman just like his sculpture, and Venus grants his wish by miraculously transforming the ivory woman into a flesh-and-blood female that later became known as Galatea. As Pygmalion lays her down on a bed, kisses her lips, and touches her breasts, the ivory softens like wax and, writes Ovid, “She was alive!”3

The outlines of the Pygmalion myth—and the idea of a simulated woman who comes alive—would be echoed over the centuries ahead in cultural images revealing men’s enduring fantasy about fabricating an ideal female—a beautiful creature he lovingly clothes and adorns, a woman who is pliant and compliant and answers all his needs, an artificial female that is a superior substitute for the real thing. These simulated women were often shaped not only by men’s fantasies but also men’s beliefs about women themselves—their inherent traits or “nature,” their usual behavior, and their proper (culturally assigned) social roles.

The Pygmalion myth, infused with a sense of magic and sensuality, was appealing to artists whose images of Galatea could be spiritual, rapturously worshipful, and also filled with erotic fantasies. Some of the earliest visual images of the Pygmalion myth were miniature paintings or illuminations in medieval and Renaissance editions of the great French poetic narrative Le Roman de la Rose (The Romance of the Rose) by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun (ca. 1275–1280). Some contemporaries considered Le Roman de la Rose an allegorical poem with thinly disguised sexuality (the rosebud is penetrated), and some contemporaries considered it immodest and an invitation to lust.4 Medieval illustrations of the poem’s section on Pygmalion, often included images of the fabrication process itself, and pictured the sculptor at work, chisel in hand, carving the figure of Galatea. One image attributed to the medieval artist Robinet Testard in a 1480 manuscript edition of the poem also had a decidedly erotic edge: Pygmalion is pictured dressing the sculpture and embracing its nude body as it lies on a bed (fig. 1.1).

The infatuation with the myth continued in later centuries and particularly flourished in eighteenth-century European literature and art. In 1771, Jean-Jacques Rousseau had greatly helped popularize the myth by writing his one-act opera Pygmalion—a scene-lyrique with musical accompaniment—and his work was one of the first to use the name Galatea for Pygmalion’s sculpture; the name didn’t appear in Ovid’s version of the Pygmalion myth but did appear in his retelling of Acis and Galatea in Metamorphoses.5

Even before Rousseau, eighteenth-century artists had been captivated by the story and, in particular, the moment of transformation as the sculpture comes alive.6 Eighteenth-century Venetian artist Sebastiano Ricci in 1717 captured that magical moment when Pygmalion looks on with ecstasy as the sculpture is animated, and in French artist Jean Raoux’s painting Pygmalion, created the same year, Pygmalion watches in wonderment as the statue’s colors change from marble-toned legs to her lively vivid red lips and blond hair. Here, Venus touches her head (the brain in the sixteenth century was considered the seat of the soul) while the god Hymen checks her pulse for life.7

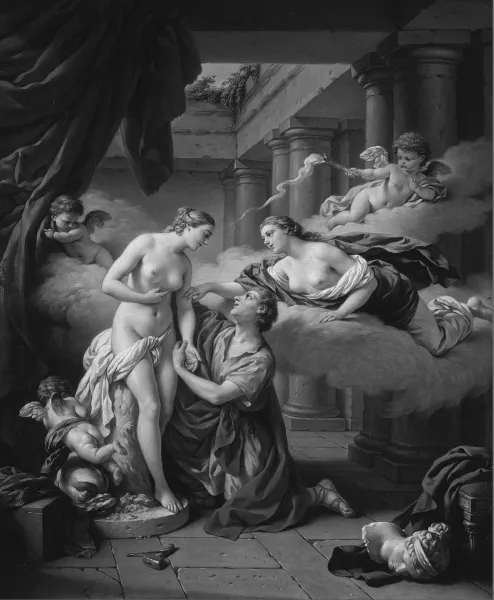

One of the more intriguing versions was Louis-Jean-François Lagrenée’s 1777 painting Pigmalion [sic] dont Venus animée la statue (Pygmalion whose statue has been brought to life by Venus), which features images of Venus touching the sculpture and a kneeling Pygmalion feeling for her pulse in her wrist. There are also three cupids, including one carrying a torch with its fire and smoke angling in a diagonal directly toward Galatea’s face, as though it too is illuminating and enlivening her (fig. 1.2)—a motif seen in James Whale’s campy 1935 film Bride of Frankenstein where the fiery zigzag of lightning animates the simulated woman and brings her to life.

Nineteenth-century British Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones in the fourth of his four-painting series on Pygmalion, Pygmalion and the Image: The Soul Attains (1875–1878), pictured Pygmalion kneeling in awe and almost worshipful of his statue, but other nineteenth-century European artists continued to be attracted to the erotic allure of the myth, seen in the sensuous curves of Auguste Rodin’s sculpture Pygmalion and Galatea (modeled 1889, executed 1906) and artist Jean-Léon Gérôme’s high-finish nineteenth-century academic painting Pygmalion and Galatea (ca. 1890), which vividly presented the skin tones of the beautiful female sculpture gradually changing from white to pink and Cupid (Eros) speeding the process by shooting an arrow of desire (plate II).8

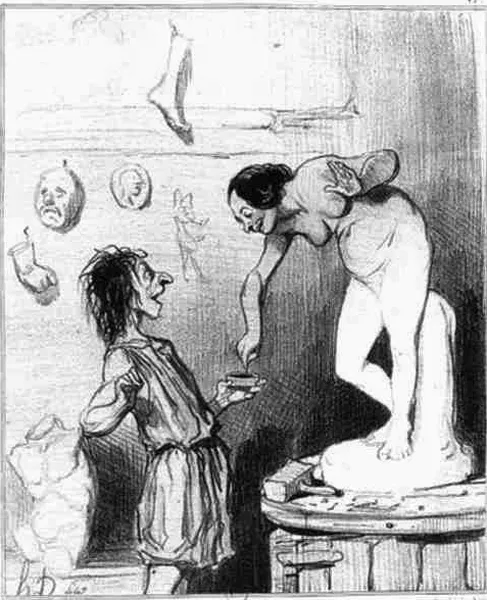

But not all Pygmalion images were this metaphoric, soulful, or serious-minded. Comic artists delighted in picturing their Galateas not as objects of men’s desire but as independent, outré women with their own agendas. In his satirical, cheekily pornographic eighteenth-century print Modern Pygmalion, British artist Thomas Rowlandson presented the nude Galatea straddling and sexually fondling the reclining Pygmalion, and French artist Honoré Daumier in his comic lithograph Pygmalion (1842) lampooned the myth as Galatea impishly reaches down to put a finger in the artist’s snuffbox (fig. 1.3).

Writers, too, were captivated by the comic potential of the Pygmalion myth, and George Bernard Shaw’s 1912 play Pygmalion offers its wittiest treatment. In Ovid’s telling of the tale, an artificial woman, a female simulacra, comes to life, but in Shaw’s version, Eliza is a modern-day Galatea with a difference: she is a lively, outspoken young woman who resists being transformed into an artificial genteel lady. The feisty Eliza ultimately balks at being a mere doll, a surface simulation, a product of men’s technological prowess and ingenuity. She is a far cry from the women in two earlier versions of the Pygmalion myth: Galatea in British playwright W. S. Gilbert’s nineteenth-century comic drama Pygmalion and Galatea (1870) and the mechanical Amelia in E. E. Kellett’s story “The Lady Automaton” (1901).

Though very different in conception, these three works of literature present a confluence of two cultural streams: men’s age-old fantasies about crafting artificial women and their fascination with mechanical and manufactured reproductions. During the late nineteenth century, new methods of technological reproduction were being developed, including methods for creating sound reproduction, after Thomas Edison patented his first phonograph in 1877. Manufacturers were also developing new methods for producing industrially made reproductions of works of art, including the use of electrotyping and cast iron to make copies of sculpture, and home furniture as well.

W. S. Gilbert, Pygmalion and Galatea

Literary and visual portrayals of the Pygmalion myth are often very much products of their times, especially so in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century British dramas and stories, which were shaped not only by the emerging technological developments in creating simulations and reproductions but also by Victorian and Edwardian conceptions of women and the playwrights’ own notions of inherent gender characteristics.

British playwright W. S. Gilbert reinforced Victorian attitudes about women in his comic play Pygmalion and Galatea, which was written in blank verse and first presented at Haymarket Theater on December 9, 1871, and one year later, at a theater in New York. His Galatea embodies the innocent, naïve, self-sacrificing female favored in Victorian conceptions of the ideal woman, although at the time the play was written debates were already simmering in England and America about women’s social status and roles. Even though middle-class Victorian codes of proper female behavior were still firmly entrenched, particularly conceptions of the “two spheres” where women were assigned the tasks of tending to domestic duties and motherhood at home while men were assigned to the outside world of business and professions, in the 1870s in England social observers saw signs of unrest in the increasingly heated debates in Europe and America about women’s access to voting rights, higher education, property rights, and greater employment opportunities.

Gilbert himself—in his immensely popular comic musical operas created in partnership with Arthur Sullivan (he was the librettist, Sullivan the composer)—was ambivalent about the status of women and what was then called the “Woman Question,” the issue of women’s roles and rights. As Carolyn Williams has suggested, the characters in these jointly created comic operas, which began appearing in 1871, often inhabit and parody “Victorian gender conventions and stereotypes in order to demonstrate their absurdity”—including the cultural insistence that women act with an “exaggerated innocence” and mask their own sexuality—but Gilbert himself was paternalistic toward his female actors, fastidiously insisting that they behave in conformity to strict codes of moralistic behavior in their private lives.9

Showing no signs of social flux or parody, Gilbert’s Pygmalion and Galatea, written before his collaboration with Sullivan, largely embraces the gender conventions of his era and the Victorian notion of female innocence while skirting the issue of sexuality. Pygmalion is a married man living not in Cyprus, but in Athens and whose sculptures of women—though often commissioned—have faces that resemble his wife Cynisca. Pygmalion considers himself an artist-magician, for he can turn “cold, dull stone” into images of gods and goddesses; as his wife says, he can turn “the senseless marble into life.” He creates a sculpture modeled on Cynisca, and the play’s complications and crises are set in motion by Cynisca herself: when she leaves on a trip, she reminds Pygmalion to be faithful to her and designates her husband’s Galatea sculpture as her proxy while she is gone: if he has thoughts of love, he should tell them to the sculpture.10

Paralleling Ovid’s myth, while Cynisca is away Pygmalion is discontented because he feels he can create images of gods and goddesses, but this can only go so far. When he prays to the gods asking that his sculpture of the beautiful woman comes to life, to his delight, he suddenly hears the sculpture say his name behind a curtain, and he exclaims, “Ye gods! It lives!” (a sentiment that would also be comically echoed years later in Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein in the iconic moment when Henry Frankenstein bends over his unbandaged female creation and says with portentousness and mellifluously, “She’s alive!”).11

The play reflects Victorian attitudes toward reproductions and simulations in the arts at the time. The Galatea that Pygmalion creates is a copy of Cynisca, a simulated woman that even Cynisca thinks is better than real. In the 1870s, when the play was written, British manufacturers of decorative wares were busy mass-producing reproductions of domestic silver using the new technological process of electroplating, and manufacturers were also covering buildings with decorative cast-iron building facades that mimicked the look of hand-carved stones. British critics like John Ruskin, however, fretted that the copies were debasements of the much-superior originals, while manufacturers not surprisingly insisted that reproductions were superior to the originals. The play becomes a gloss on creating reproductions, in this case, a lovely Galatea who comes to life from stone.12

When she first looks at the sculptural copy of herself, Cynisca views the sculpture as a kind of double—“my other self”—an image she herself considers superior to what she calls the “wife-model.” To her, Pygmalion’s sculptural copies of her are idealizations. The sculptures have a face younger than her own and are more like her image ten years ago. The copies have “outlines softened, angles smoothed away,” and this copy has a “placid brow” and “sweet, sad lips.” In Gilbert’s play, Galatea in some ways rivals and even surpasses Pygmalion’s wife in terms of her sensibilities, her moral vision, and her delicacy of feeling. But when Galatea asks Pygmalion if his wife were as beautiful as she is, he replies that when he sculpted her from marble, he made her lovelier than his wife, and that she indeed has a prototype. Says Galatea with disappointment, “Oh, then I’m not original?”13

Gilbert’s play is also shaped by Victorian gender stereotypes about the ideal woman. Before she goes away on her trip, Cynisca muses that Pygmalion’s most recent sculpture (Galatea) is superior not only because it is lovelier but also because it does not have two of women’s stereotypical female features: their tendencies to be too emotional and to talk too much. (Years later, in fiction and film, these are two of the very same features men get rid of in their idealized robot women.) Although the real woman Cynisca has vitality—she “laughs and frowns”—Galatea has no emotions. Says Cynisca of the sculpture (in a voice of resignation, good humor, distress?), “For she is I, yet lovelier than I/And hath no temper, sir, and hath no tongue.”14

In Gilbert’s play, ...