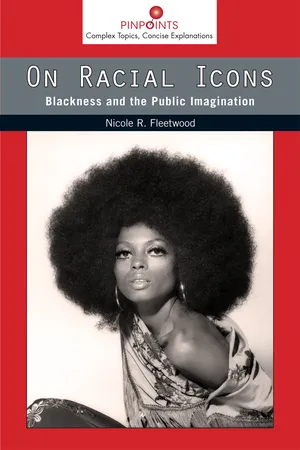

![]()

1. “I Am Trayvon Martin”

The Boy Who Became an Icon

ON RACIAL ICONS TOOK shape in the wake of the Trayvon Martin tragedy: his murder and the acquittal of his murderer, George Zimmerman. I was in the early stages of writing this book when Trayvon Martin was killed. Shortly after his death, public awareness of his murder spread internationally. I believe that it is important to preface this chapter with such a disclosure because my choice to include Martin touches on the stickier and more troubling aspects of racial iconicity: the interworkings of misfortune and opportunity, of terror and visibility, of injustice and hopefulness, of death and immortality.

In writing this chapter, I enact a mode of racial belonging and collective mourning that is conflicted in its use of substitution and that is cathartic in its attempt to make visible and to perform a long and continual process of grieving racial violence and morbidity. The significance of Trayvon Martin’s killing to national and international publics reveals how certain deaths, especially racially motivated killings, acquire representation at specific historical periods. Moreover, through this tragedy and “our” coming together to protest and mourn Martin’s killing, we might pause to consider the persistence of black vulnerability in the public sphere and how we sympathize with the suffering of some, and not of others.

On February 26, 2012, Trayvon Martin, a seventeen-year-old black American teenager, was killed while walking back to the home of his father’s fiancée from a nearby convenience store in Sanford, Florida. George Zimmerman, a neighborhood watch guard, noticed Martin walking, followed him, confronted him, and ultimately shot and killed him. After noticing Martin from his vehicle, Zimmerman called the Sanford police and reported that Martin was acting suspiciously and that he looked “like he’s up to no good” or “he’s on drugs or something.”1 Zimmerman identified Martin’s hoodie (a sweatshirt with a hood) as one of the features that marked Martin as suspicious. According to public records, the dispatcher told Zimmerman to remain in his vehicle and that an officer would be sent out to investigate. However, Zimmerman, as the saying goes (and as the history of American vigilantism and racism reveal), took the law into his own hands and pursued Martin nonetheless.

By the time the dispatched police car arrived, Martin was lying in a pool of his own blood, fatally wounded. It was not until the next day that Martin’s father, Tracy, would learn of his son’s fate. When the teenager was not home by the next morning, Tracy contacted the police to file a missing person report. Shortly thereafter, officers arrived at Tracy’s home. They showed a photograph of a dead Trayvon Martin and asked if this was his missing son.

With little inquiry or investigation, the killing was quickly filed as self-defense by the Sanford Police Department under Florida’s notorious justifiable use of force statute, most commonly known as the “stand your ground” law. Despite the fact that Sanford police questioned the credibility of Zimmerman’s account of the events, Zimmerman was released under this law.2 Even though the case was initially dismissed, these spare facts no one disputes: that Trayvon Martin was a black boy walking home, that Zimmerman deemed him suspicious, and that Zimmerman killed him.

Less clear, as cultural theorist Matthew Pratt Guterl points out, is the racialization of Zimmerman from the standpoint of familiar narratives of black/white racism in the United States. Zimmerman was assumed to be white when the news media first began reporting the case; yet as images of him began to circulate, they appeared to reveal an “ethnic identity” other than white. Later, some media outlets labeled him as “white Hispanic” and others continued to identify him as “white.” Guterl explains: “This manifest racial ambiguity helped to complicate Zimmerman’s motives, and to provide cover for those who wished to find a rational act. It was easy to think that some white trash fellow might have gotten a little crazy with a gun and shot some poor black child. It was harder to demonize a hard-working Latino, half Peruvian, or ‘white Hispanic,’ struggling to protect his precious property values.”3

The story of that tragic winter’s night in central Florida does not end there, although Martin’s life did. While the local authorities readily dismissed the case, Martin’s death reached international attention in large part due to the commitment of his parents, Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin, to seek justice for their son’s murder. Their efforts were aided by the viral transmission of information through the Internet and the strategic use of Martin’s image as part of their campaign for justice. In fact, many people learned about Martin’s death through online petitions that were posted on Facebook and other social network sites demanding that Sanford’s district attorney’s office bring charges against Zimmerman. The outcry and protests of millions, including several high-profile celebrities and public figures, led to an inquiry by the Department of Justice and eventual charges against Zimmerman.

A prominent strategy to garner awareness of Trayvon Martin’s death was the circulation of photographs of him as an “ordinary” teenager. I place “ordinary” in quotation marks because there is little doubt that a black teenage boy is never seen as an “ordinary” American, let alone an “ordinary” child who deserves protection and guidance of adults and public authorities. Nonetheless, the photographs used in awareness campaigns by supporters of “Justice for Trayvon” are striking and compelling, given the context of his death and the state’s efforts to absolve his murderer.

One photograph used in protests is a black-and-white self-portrait by Martin, known as a “selfie” in the social media landscape. The selfie is a form of representation that intimately projects how one wants to be perceived by an audience, especially among one’s peers in the digital media realm. The selfie is a contemporary form of vernacular photography, the most widely practiced genre of photography since its inception. In its everydayness and the ease of access that consumers have to photographic software and technology in the contemporary era, the selfie makes self-portraiture a more common practice than in any other period in history. Although it often appears fleeting and can be erased in an instant by digital technology, the selfie is nonetheless part of the storied genre of portraiture. Like other portraits, the selfie is a deliberate representation of a public persona, a mode of self-conscious “sitting” in front of a photographic lens. Whether playful, sensuous, earnest, or aspirational, the selfie suggests a desire for recognition; it is a request for acknowledgment, an appeal to be a subject of value.

In this now famous self-portrait, Martin looks down into the lens with one shoulder raised as if he is leaning. He wears a hoodie. The lighting from above and the cap shaping his face create a halo effect. In the sheath provided by the hoodie, Martin’s face appears to float. He hovers and levitates, as his eyes peer out from under his hood. The affect is that of a foreshadowing, a speaking to audiences from the silence of death. Even as it feels as if it were a sort of premonition, Martin’s selfie is also a performance of presence. He is, at that moment, alive, self-documenting and archiving his presence for meaning and circulation. His downward tilted eyes avoid contact and yet they reveal an inquisitive gaze. This “ordinary” boy has captured an image of himself that, after his murder, circulates as a posthumous icon. The boy, who died in large part due to a “look” that rendered him suspect in public, becomes venerated through a self-image that captures that very look. With this singular photograph, we see how image and context work together to produce an icon.

As lethal and vile as racial intolerance and racial violence are, the forces of love, recognition, and the pursuit of justice are crucial to the emergence of Martin as an icon. We—as a public—know of Martin’s harrowing fate because of the courage and dedication of his parents, who began an online campaign through a petition demanding the arrest of Zimmerman circulated on the website Change.org.

The parents’ efforts led to other marches and protests. Through the embrace of Martin’s photograph as part of the “Justice for Trayvon” campaign, we witness the emergence of an iconic photograph, but we also isolate an iconic form—the hoodie—one that has resonated in public culture for years but that has become more complexly articulated in the wake of Martin’s murder. The hoodie is an article of clothing identified with a generation of urban black young men and, for Zimmerman and many others, is a marker of black criminality. This article of clothing is steeped in the history of racialized style in the United States, in ways similar to the zoot suit of the 1940s. The zoot suit, too, was linked to racialized violence and the criminalization of black and Latino youth who wore the suit in defiance of wartime (white) patriotism.4 Invoking the slang term hood (as in black and Latino poor and working-class neighborhoods) as well as the functionality of a hood attached to a sweatshirt or jacket, the hoodie acquired popularity through its association with hip-hop culture and urban black athletic wear starting in the late 1980s and 1990s. For example, on the promotional material for the 1992 “hood film” Juice directed by Ernest Dickerson, late rapper and actor Tupac Shakur poses in a dark hoodie with a look of foreboding in his sideway glance. While the hoodie registers urban, young, masculine, and black, increasingly it has become an article of fashion for non-urban, non-black, and non-youth groups. One of the most notable examples of its wearing is by Facebook cofounder Mark Zuckerberg, who chooses to wear his signature hoodie to corporate board meetings and in public appearances.5

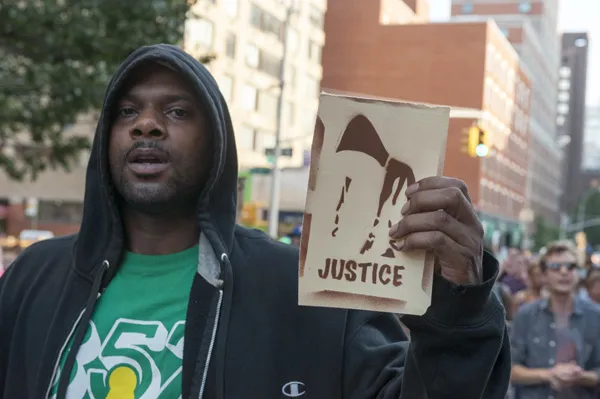

The use of Martin’s selfie in campaigns for justice led to a form of protest in which millions of people in countries around the world donned hoodies, posed before a camera, and proclaimed “I am Trayvon Martin.” The protests took place on multiple platforms. At rallies small and large across the country, groups showed up in hoodies with signs declaring, “I am Trayvon Martin” or “We are Trayvon Martin.” Selfies were posted on personal pages of social media networks with members hooded, somber, and staring into the camera. Others used a black-and-white silhouetted graphic of a male profile in hoodie. The Miami Heat basketball team took a group photograph of the team hooded with heads bowed. Protestors who claimed “I am / We are Trayvon Martin” were politically, racially, ethnically, linguistically, and geographically diverse. They were representative of how complexly heterogeneous the twenty-first-century “American public” is. The protest portraits in this case expressed an infinite dynamism and multiple embodiment of racial iconic form, even in its tragic outcomes.6

The reaction of many to Martin’s death registers subtle and enormous changes in the United States that can only be briefly sketched out here. It marks the profusion and rapid circulation of representation in the contemporary era. The number of photographs produced has mushroomed, largely because of the accessibility and relatively low cost of digital cameras embedded in portable consumer devices. The impact of digital photography continues to expand with the growth in photo-sharing sites.7 In addition, the justice for Martin protests speak to the changing perception and reception of the icon and what it means to have “staying power” in a cultural climate where the consumption of images occurs more often involuntarily and with such rapidity and plenitude that it makes it challenging to hone in on a singular image. Furthermore, these photo-based protests signal generational and racial shifts among many black and non-black protestors. Masses of protestors imagine and (temporarily) identify with blackness in ways that are not through minstrelsy, slumming, or parody. Instead, one could argue that these images symbolically demonstrate an identification with racial isolation, profiling, and forms of abject suffering associated with certain groups of blacks and other vulnerable populations in this country and elsewhere. In this light, many non-blacks are able to recognize a young black male as a sympathetic character—as one with whom they form a deeply emotional and performative attachment, a type of claiming—and to see the machinations of structural and quotidian racism to portray him as other.

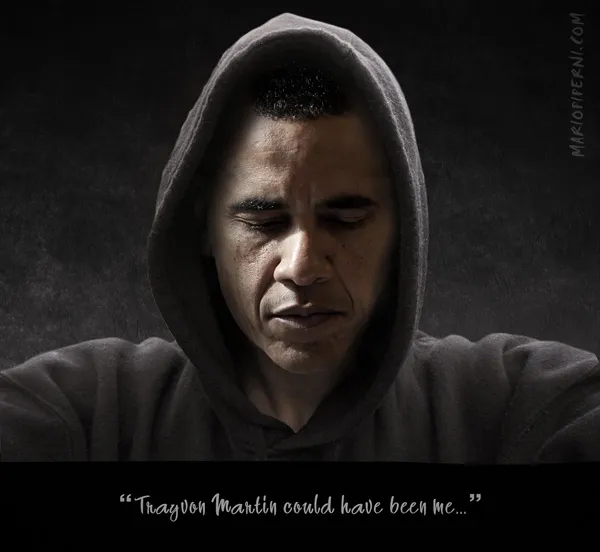

The emotional waves of identifying with Martin reached the White House. Whether rooted in perceived or actual public pressure or a personal sense of the shared experience of racial profiling, President Barack Obama felt compelled to link his life outcomes to those of Trayvon Martin. A month after Martin’s murder, the president spoke publicly about the killing. Many have argued that, as president, Obama has been cautious in speaking about race because of the expectations of many that he should address the significance of race in the nation’s past and present. After growing tensions about Martin’s murder and pressure from the public to see justice in Florida, Obama went on record stating, “You know, if I had a son, he’d look like Trayvon.”8 The president’s words affirmed what many sympathetic to Martin’s parents felt. For some on the front line of protesting, there was cautious hope that Obama would be more vocal and active in his stance against racism. Contrarily, he was widely criticized by politically conservative commentators and constituents and was accused of race-baiting. Yet even still, after the acquittal of George Zimmerman, Obama seemed to identify even more closely with Martin. He spoke of his own experiences of being racially profiled and then stepped into the dead boy’s shoes by claiming, “Trayvon Martin could have been me.”9 His statement both led some to question what connects Obama to a seventeen-year-old boy who died s...