![]()

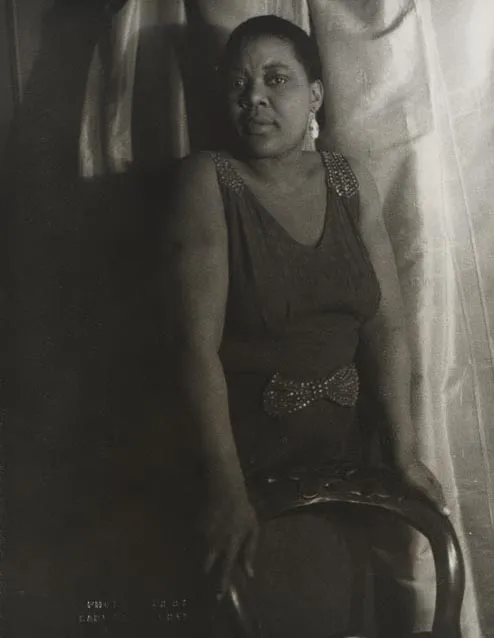

1 / Vivid Lyricism: Richard Wright and Bessie Smith’s Blues

This chapter highlights Richard Wright’s alignment of his work with Bessie Smith’s, thus establishing the relationship between male writers and female singers that the next two chapters will also explore. Although Wright’s fiction often depicts black song as a feminized threat to black male resistance, his unpublished 1941 essay “Memories of My Grandmother” attunes us to moments in Wright’s work when feminized lyricism itself functions as a medium of resistance. Wright uses such lyricism to protest black alienation from U.S. society in general and from the domain of the literary in particular. His widely neglected film of Native Son (1951) takes this revalorization of feminized song a step further by granting black female singers themselves the voice of critique, or what I term outsider’s insight. Hence, even Wright, whose work is generally thought to devalue both black women and black music, creates nonfictional and cinematic works in which song becomes the medium of expressive alliance between black men and women. Wright does not imagine that either singers or writers can escape social restrictions. But what aligns him with blues singers like Smith is that they creatively manipulate racialized social exclusion in similar ways—namely, by joining forces with other “exiles” to create incisive, vivid responses to disenfranchisement.

In 1949, Wright traveled to Buenos Aires to film the novel that, nine years earlier, had made him the biggest mainstream African American literary celebrity since Frederick Douglass. Wright himself starred as Native Son’s protagonist, Bigger Thomas, the young black Chicagoan who inadvertently murders his white employer’s daughter, goes into hiding, murders his own lover, Bessie, and is captured, tried, and sentenced to death. Wright’s starring role alone made the film a landmark event—as Kyle Westphal notes, it’s hard to think of “another film where an American author literally enacts his major novel”—and, despite the dubious decision to have Wright play a character who was by then twenty years his junior, the film received rave reviews when it opened in Argentina in 1951.1 But when it opened in New York three months later, critics panned it, and its U.S. reception has determined its fate ever since.2 James Baldwin, a master of the elegant assault, may have delivered the most memorable blow in his essay on Wright, “Alas, Poor Richard” (1961). There Baldwin simply notes that he and a friend ran into Wright one day, shortly after Wright had “returned from wherever he had been to film Native Son. (In which, to our horror, later abundantly justified, he himself played Bigger Thomas.)”3 Aside from this glib (and, I would say, unjustified) review of Wright’s acting, the few scholars who have addressed Native Son’s cinematic incarnation have generally framed it as a “filmic fiasco”—or, at best, a “fascinating failure.”4

It is unclear whether Baldwin actually saw Native Son, but if he had, one wonders what he would have made of the “makeover” the film gives Bigger’s girlfriend, Bessie Mears. Especially considering Baldwin’s own persistent engagement with black women singers like Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday, he may have been intrigued to see that Bessie, a long-suffering victim in the novel, becomes a beautiful singer (played by Gloria Madison) in the film. A pivotal scene dramatizes Bessie’s transformation from page to screen. In the novel, Bigger accompanies his employer’s daughter, Mary Dalton, and her white boyfriend, Jan Erlone, to a South Side restaurant called Ernie’s Kitchen Shack; he dolefully encounters Bessie there, drinking at the bar. In the film, the Kitchen Shack becomes a stylish nightclub at which Bessie is the featured performer. Dressed in a lovely white evening gown, Bessie performs a sensual song while encircling Bigger and his new “friends.” Bigger’s mother, Hannah, though not as radically transformed as Bessie, also acquires a new unsentimental grandeur in the film, particularly through another scene of song. In the novel, Hannah sings a hymn that “irks” Bigger; we are meant to understand that the song represents a fatalistic response to black suffering that Bigger can neither accept nor effectively challenge.5 Yet in the film, when Hannah prays along to a hymn at a church service, the congregation seems to threaten not Bigger’s agency but rather the white policemen and investigators who have entered the church to hunt him down.

These scenes of black women and song are surprising because they simultaneously unsettle two rather basic critical assumptions about Wright and his work. The first is that, as feminist critics have long pointed out, Wright consistently denigrates black female authority.6 The second is that he does not value African American music.7 The latter assumption thrives in spite of Wright’s thorough and supportive engagement with black music in “Blueprint for Negro Writing” (1937) and White Man, Listen! (1957)—works which, as I noted in the introduction, were important to Black Arts theorists. In light of influential writings by critics like Ralph Ellison and, later, Henry Louis Gates Jr., both of whom downplay Wright’s investment in the blues, it is easy to forget that Wright himself is a key force behind Black Arts valorizations of music—and, indeed, that it is Wright’s work which occasions Ellison’s seminal definition of the blues, in “Richard Wright’s Blues” (1945), as “an autobiographical chronicle of personal catastrophe expressed lyrically.”8 Still, the notion that Wright devalues black music is not entirely misguided, for Wright’s treatment of this subject is ambivalent, and even his positive readings of the spirituals and blues do not express the proud love of black music that animates the work of Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and his other contemporaries. Indeed, as Wright’s depiction of Hannah’s hymns in the novel Native Son suggests, his work often problematizes the black musical practices from which Ellison would claim Wright was tragically alienated.9

Standard accounts of Wright’s work constellate his sexism, his supposed neglect of black music, and his writerly style. Lyricism is not a quality for which Wright is known—this despite the fact that Wright himself rejects “simple literary realism” in “Blueprint for Negro Writing” and encourages black writers to engage the “complexity, the strangeness, the magic wonder of life.”10 Such comments notwithstanding, Wright is framed as a naturalist-cum-existentialist whose writing expresses the dire facts of black life in hard-boiled prose. There is no place in such a project for the celebration of music or the stylization of what might be termed “musical” writing. Thus, Gates locates “the great divide” in African American literature in the “fissure” between the “lyrical shape” of Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) and the “naturalism” of (the novel) Native Son (1940).11 Wright’s supposedly amusical prose can appear to be an extension of his supposed machismo. This interpretation is especially tempting if one takes his scathing (and sexist) critique of Hurston’s novel, in which he claims that Hurston’s “prose is cloaked in that facile sensuality that has dogged Negro expression since the days of Phillis Wheatley,” as a countermanifesto for his own work.12

The impulse to associate Wright’s masculinism with hard-boiled writing would comport with early twentieth-century developments in the gendering of prose styles. As John Dudley points out, lyrical or highly wrought prose was marked as effeminate and decadent by influential U.S. naturalists like Frank Norris and Jack London, for whom “the figure of the aesthete . . . came to represent the ineffectual languor of a feminized aristocracy.”13 Wright’s own influential predecessors, in other words, coded no-frills realism as “masculine” writing and rejected the soft lyricism of “feminine” prose. Yet this chapter is sparked by my own conviction that Bessie’s and Hannah’s cinematic incarnations encourage us to develop an alternative critical narrative about Wright’s musical, gender, and prose politics—one that could account for these powerful cinematic scenes in which Wright literally makes his work sing, as well as for figuratively “songlike” passages in his writing. What do we make, for instance, of the sonorous, visionary writing—even purple prose—Wright deploys in texts like his memoir Black Boy (1945), when he describes “the quiet terror that suffused [his] senses when vast hazes of gold washed earthward from star-heavy skies on silent nights”?14 What does it mean that Ellison calls such moments in Black Boy and in Wright’s valedictory account of the Great Migration, 12 Million Black Voices (1941), “lyrical,” that David Bradley claims that “in 12 Million Black Voices Richard Wright sang,” and that both Ellison and Baldwin compare Wright’s work with Bessie Smith’s blues?15

I address these questions through Wright’s analysis of Smith’s blues in “Memories of My Grandmother,” which is perhaps the only work in which Wright expresses unqualified admiration for a black female artist. Although the essay was intended as a preface to Wright’s short story “The Man Who Lived Underground” (1941), it has never been published. Indeed, its “underground” status reflects the extent to which Wright’s engagement with Smith (like his several depictions of female singers) remains muted in the critical imagination. Although Wright habitually treats black folk expression as a generic body of “authorless utterances” created by “nameless millions,” his citations of Smith’s work are an important exception to this rule.16 For instance, as I discuss at the end of this chapter, Wright extensively cites Smith’s “Backwater Blues” (1927) in White Man, Listen!, and he even allegedly planned to write Smith’s biography. It is in “Memories,” however, that Wright most fully engages with Smith’s work. Writing about Smith’s “Empty Bed Blues” (1928), he asserts that the details in blues songs “have poured into them . . . a degree of that over-emphasis that lifts them out of their everyday context and exalts them to a plane of vividness that strikes one with wonderment.”17 Wright suggests that the intensity of this vision is produced by and bears witness to black Americans’ “enforced severance” from dominant society; the “everyday” looks different, even extraordinary, from the margins.18 This claim demonstrates the rhetorical process that Paul Gilroy describes with regard to black Atlantic expressive cultures, by which “what was initially felt to be a curse—the curse of homelessness or the curse of enforced exile—gets repossessed. It becomes affirmed and is reconstructed as the basis of a privileged standpoint from which certain useful and critical perceptions about the modern world become more likely.”19 For Gilroy, this affirmation of alienation is a social philosophy that can illuminate literary thematics. I contend that this subversive affirmation also helps us reread—and even re-gender—Wright’s literary style.

In Smith’s music, Wright identifies a quality that I call vivid lyricism. The phrase refers to the practice of exploiting the sound of language to enhance visual description. The concept allows us to theorize the sonorous descriptive prose style Wright effects in Black Boy and 12 Million Black Voices.20 I see this prose style as enacting the promise Wright hears in Smith’s blues: that social exclusion might yield uniquely intense, musical visions of the world. As I have noted, Wright resists “simple literary realism” in “Blueprint.” He states that the black writer’s “vision need not be . . . rendered in primer-like terms; for the life of the Negro people is not simple.”21 “Memories” helps us see that when Wright encourages writers to capture the “complexity, the strangeness, the magic wonder of life that plays like a bright sheen over the most sordid existence,” what is at stake is not just fidelity to the complexity of black life but fidelity to an intensified vision of the world that Wright associates with social exclusion.22 Wright’s vividly lyrical prose style dramatizes the “oblique vision” Wright suggests such exclusion produces; it also showcases the author’s struggle for and extravagant achievement of the literary.23 Thus, this style both critiques and embraces the author’s enforced “severance” from dominant U.S. society generally and the domain of the literary specifically.

While this literary style may be linked with W. E. B. Du Bois’s oft-noted (and sometimes disparaged) “high Victorian” prose, the difference is that Wright deploys this style at a moment when it has passed out of literary currency, thanks in part to new aesthetics of proletarian art. In this context, Wright’s use of the style becomes all the more unusual and makes its own statement. Namely, at a moment when descriptive expressionism is coded as “feminine,” Wright revises the valence of “feminine” writing by decoupling “feminine” from “decadent.” In short, whatever Wright’s intentions, he uses a feminized form of expression to stylistically protest racial exclusion.

His collaborative work in visual media moves the power of feminized song from the level of style to that of representation, thus revising Wright’s earlier fictional depictions of black women’s songs. 12 Million Black Voices, the photo-text project on which Wright collaborated with photographer Edwin Rosskam, ascribes the power to embrace and protest exclusion to black women singers themselves. Wright’s film of Native Son, an independent production directed by Pierre Chenal, likewise represents the sustaining, subversive potential of female song. But in the film, black female characters embody their own outsider’s insight, which is precisely the vision Wright’s lyrical prose in Black Boy and 12 Million serves to dramatize, and the vision Wright hears in Smith’s blues.

These collaborative projects revise the musical and gender politics of Wright’s earlier fiction in part because they release Wright from the singular responsibility of making meaning in words and thus diminish his fear of misrepresenting himself and his subjects—specifically, of inviting sentimental, emasculating readings of his work. What I am suggesting is that Wright’s ambivalent relationship to feminized forms of expression (whether literary or musical) has at least as much to do with his anxiety about audience as it does with his own feelings about women. Fear of figurative emasculation may be hard to separate from misogyny, but what I call Wright’s “reception anxiety” may go further in helpin...