![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Development of the Tobacco Economy in Puerto Rico

From the time the grower delivers his crop until it is finally exported or manufactured the tobacco goes through from ten to twenty operations, one bundle or hand at a time—in some operations, one leaf at a time.

—Charles Gage, 1939

The efforts of tobacco growers to secure beneficial legislation, economic protection, and financial relief for their crop cannot be understood without first examining the particularities of the tobacco sector during the first decades of the twentieth century. Tobacco cultivation in Puerto Rico experienced cycles of expansion and contraction during this time in response to local conditions, global economic realities, and shifting consumer trends. This chapter presents a comprehensive analysis of these cycles. The tobacco sector expanded rapidly and consistently until 1929, increasing in importance as a source of commercial exports. From 1907 through 1917, tobacco was the third-most-important commercial crop produced on the island after sugar and coffee. In 1918, tobacco surpassed coffee as the second most important commercial crop after sugar. The export value of tobacco on the island peaked in 1920, when tobacco surpassed sugar and represented 38 percent of the total value of commercial crops (sugar accounted for 25 percent).1 From 1921 to 1940, tobacco remained the second-most-important commercial crop after sugar. Tobacco cultivation was not only important commercially, but it was also crucial as a source of income for the rural population. In 1910, over 14 percent of all farms on the island reported the cultivation of tobacco leaf, and by 1940 that proportion had increased to 30 percent.2 In addition, the sale of unprocessed tobacco leaf and the manufacturing of tobacco products became essential to the insular government as revenue providers, constituting up to 30 percent of the insular state’s income per year during the 1930s.3 In short, tobacco’s importance as a commodity for the U.S. market, for the well-being of the rural population, and as an income producer for the insular state was marked and increased throughout this period.

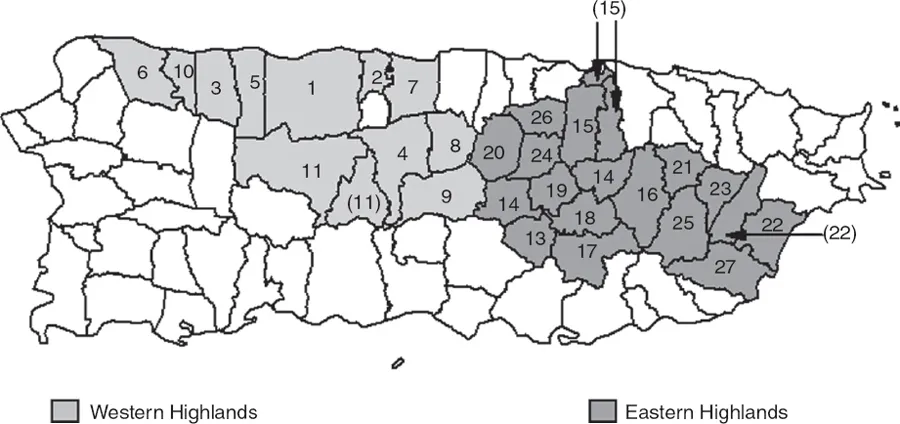

This chapter also examines two distinct tobacco regions.4 (See figure 1.1 and table 1.1.) The first includes the municipalities in the eastern highlands, where tobacco leaf cultivation first expanded after 1898. The darker, shade-grown tobacco leaf cultivated in this region was considered of high quality and admired for its taste; as such, it fetched higher prices per pound in the market. The second region includes those municipalities in the western highlands, where the expansion of tobacco cultivation occurred later and relied heavily on chemical fertilizers. The brighter, coastal and semi-coastal tobacco cultivated in the western highlands was used as filler for cigarettes and cigars, and commanded much lower prices in the market than the darker tobacco of the eastern highlands.5

Although data analysis may seem an impersonal way of understanding human political and social processes, it provides a concrete framework through which these very processes can be examined. Puerto Rican tobacco growers were able to negotiate necessary benefits not only because the sector was important for the insular government as a revenue producer, but also because it provided employment for a significant sector of the rural population of Puerto Rico. For example, fluctuating prices paid for tobacco leaf may be indicative of how much tobacco is available to sell or how smokers’ preferences change over time; or it may determine how many farm laborers will be hired for a season. Therefore, by including precise economic data, a clearer, more complete picture of the tobacco sector of Puerto Rico emerges.

FIGURE 1.1 Tobacco-Growing Regions of Puerto Rico.

TABLE 1.1

TOBACCO-GROWING REGIONS IN PUERTO RICO, 1899–1940

But tobacco leaf cultivation was not a post-1898 phenomenon, and so its history must begin during the time of the Taínos, Amerindians who lived in Puerto Rico and throughout the lands on the Caribbean Sea at the time of Spanish contact. Called cogiba or cohiba, Taínos would dry the leaves in the sun, grind them, and smoke the ground leaves in a Y-shaped wood pipe called tabaco.6 Taínos also twisted the dried leaf, wrapped it with a smoother leaf called a pura, and smoked it much like cigars are smoked today. When the Spanish settled the conquered island after 1508, they quickly became users of the aromatic leaf, bringing it to Europe during their travels, and trading it for other goods, both legally and as contraband. A market soon developed for leaf tobacco, and tobacco cultivation expanded not only in Puerto Rico, but throughout the Caribbean. Theoretically, all exports were destined for Seville, where the Casa de Contratación, a Spanish government agency that monopolized the colonial trade, would be responsible for marketing the leaf. In reality, much of the tobacco grown was sold at local ports throughout the Caribbean, thereby circumventing the Spanish quinto, a 20 percent tax on traded goods. Because the Spanish Crown was unable to control such rampant trade, it prohibited the cultivation of tobacco for commercial purposes.

The prohibition was ineffective and did not stop the cultivation or the trading of tobacco leaf. By the early seventeenth century, the Crown shifted its policies in order to reap the benefits of the continued demand for tobacco. A decreto real of 1614 permitted tobacco cultivation for commercial purposes and Puerto Rican tobacco production expanded as a result. By the middle of the seventeenth century, a pound of tobacco leaf was valued at 2 reales in the export market, and it was estimated that the total value of exports was about 8,000 reales annually.7 In 1784, the Crown opened a Real Factoría Mercantil in Puerto Rico charged with the exclusive right to export tobacco leaf and to secure the product from island farmers. This meant the establishment of a buyer’s monopoly for tobacco, which controlled the prices paid to agriculturalists for their product.

Island tobacco farmers, dissatisfied with Spanish monopoly policies, responded with an increase in illegal commerce with foreign nations, principally the English and French. The Crown finally relented in 1815 and reduced export taxes, not only for tobacco, but also for other products making up the export sector such as sugar, ginger, hides, and indigo. By 1828, almost 2.5 million pounds of tobacco were produced on the island, and production increased yearly until it peaked in 1880, when it was estimated that Puerto Rico produced over 12 million pounds of leaf.8

The U.S. occupation in 1898 and the resulting economic policies accelerated the expansion of the active tobacco sector. The incorporation of Puerto Rico into the tariff structure of the United States also allowed the easy flow of U.S. capital into the island’s economy for the establishment of tobacco manufacturing plants.9 Unlike what would occur in the sugar sector, however, U.S. investment in the tobacco sector remained largely in the manufacturing area, leaving the agricultural process largely in the hands of the Puerto Rican farmers.

CHARACTERISTICS OF PUERTO RICAN TOBACCO

Three types of tobacco were grown in Puerto Rico, classified according to their geographic characteristics: interior, coastal, and semicoastal.10 Filler tobacco was cultivated in the interior highlands of the island, especially in the eastern highland region. Filler tobacco, which accounted for 95 percent of the total island tobacco crop, was of the Virginia No. 9 and Utuado X varieties of tobacco classified as Type 46.11 The characteristics of Puerto Rican tobacco made it appropriate for blending with other types of filler tobacco from the United States for the manufacturing of cheaper cigars. Because of the smoothness, aroma, and distinctive taste of Puerto Rican tobacco, American manufacturers compared it to Cuban tobacco. For the manufacture of higher priced cigars, Puerto Rican tobacco would be used alone or blended with Cuban filler tobacco.12 Unlike Cuban tobacco, however, Puerto Rican tobacco was not subjected to a tariff when it was imported into the United States, thereby making Puerto Rican tobacco economically advantageous to the manufacturing sector without any sacrifice in quality.

Coastal tobacco was grown on the northwestern and southeastern littorals of the island. It was not as carefully cultivated as interior tobacco, and was not considered to be of high quality. The leaf was short and heavy in taste, and coastal tobacco was mostly used to produce chewing blends, since the salt from the sea made its taste unpleasant for smokers but mellow for chewers. Coastal tobacco was also used as scrap for very cheap cigars and cigarettes.13

Semicoastal tobacco was cultivated in the island’s lower altitude valleys located close to the coastline, and its quality fits somewhere between that of interior and coastal tobacco leaf. The slightly higher elevation of these tobacco fields, located on terrain that changed from coastal plain to mountains, protected the leaf from the searing heat of the coast. Their proximity to the saline coastal air, however, affected the taste of the leaf grown there. Semicoastal tobacco was mostly used as filler for cigars and cigarettes.14

Shade-grown wrapper tobacco, the most exquisite and valued of the island’s tobacco leaf, was produced on the island between 1902 and 1927 on lands owned by a subsidiary of the Porto Rican–American Tobacco Company (PRATC) in the La Plata Valley in Aibonito, Cayey, and Comerío and in the lowlands around Caguas, Gurabo, and Juncos.15 Wrapper tobacco was used as the outer leaf for high-priced cigars. Because it was the first leaf a smoker would taste, great care was taken in its cultivation. However, the shift in consumer taste to cheaper cigars and cigarettes during the 1920s, along with the labor-intensive nature of its cultivation, eventually made production of shade-grown wrapper tobacco unprofitable for the PRATC. In 1927, its production was ended and the land on which it was grown was sold to the insular government as well as to individual farmers.

THE CULTIVATION OF THE TOBACCO PLANT

Tobacco cultivation can be separated into different and specific stages: planting and cultivation, harvesting, curing, and fermenting. The tobacco season usually began in June or July with a careful plowing of the fields. By early August, the land was plowed and cleaned of all weeds, rocks, or other debris, and farmers would use oxen to dig ditches about ten inches deep and three feet apart.16 Farmers would then scatter tobacco seed by hand into the ditches and water them twice per day. Those who had more abundant financial resources would use cheesecloth to cover the seedbeds from pests and the weather for the first two weeks after the planting. The seeds would germinate and grow into seedlings in thirty-five to forty days, but were not considered ready to transplant until after sixty to sixty-five days. Seedlings were then planted every thirty-two to forty-eight inches in rows that were set fourteen to eighteen inches apart.17 The transplanting would begin as early as the final weeks in September, although most farmers preferred to...