![]()

CHAPTER 1

The “Evolution” of Service and Sustainability

The Beginning

The creation of the world, whether by the “big bang” or by force majeure, defined the dimensions of space and time and produced the physical resources that together constitute our planet. This was followed by a series of extended and complex evolutionary processes characterized by changes in energy and material that shaped the natural environment into the form we recognize today and which define the animate and inanimate worlds. With the emergence of the human race, revolutionary processes driven by changes in technology and in how human beings comprehend themselves and their surroundings led to social, economic, and environmental changes with far-reaching consequences.

To sustain life, nature produces and supplies in concert a variety of products that can be roughly categorized as physical resources or tangible values (i.e., goods such as air, water, food, and minerals) or nonphysical resources or intangible values (i.e., services like pollination and temperature regulation). From the dawn of humanity, humankind survived by exploiting these resources, which were provided via myriad natural processes that today are collectively known as ecosystem services (Figure 1.1) (Gretchen 1997). These can be divided into the four general categories of provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural services (Table 1.1). Most natural processes are cyclic, which ensures that minimal amounts of materials and energy are used and/or lost and that resources are regenerated.

Figure 1.1 Ecosystem services

Table 1.1 Ecosystem service categories

Although each ecosystem service category refers to specific natural processes, they are intricately intertwined in terms of both function and output. Provisioning services are all the tangible goods produced by ecosystems—from raw materials and food to pharmaceuticals and genes. In parallel, nature also provides intangible regulating services such as climate regulation, waste decomposition, and disease control. These material and nonmaterial values are backed by supporting services, like nutrient recycling, pollination, and water and air purification, all of which are essential to perpetuate the production and delivery of all other services. Finally, in contrast to the first three categories—which reference naturally occurring processes that happen regardless of whether there is a human presence—the category of cultural services relies on people’s perception. Thus, nature also supplies cultural services in the forms of spiritual and esthetic experiences that enrich and develop people’s cognitive selves as well as their social and cultural lives.

From the beginnings of the human race, with the appearance of the first human species (i.e., Homo genus) about 2.5 million years ago, ecosystem services also determined people’s way of life. The earliest human societies comprised hunter-gatherers whose survival depended on their daily collection of goods—from water and food to stone tools and shelters—directly from nature. Moreover, people also had to exploit nature’s intangible provisions, and in the process, they molded their life course according to the natural order reflected in the cyclicality of day and night and the seasons of the year. As such, the members of the wanderer-forager society were actually ecosystem service consumers, and all natural goods and services were delivered in a one-sided, unidirectional mode (Figure 1.1). Nonetheless, though people did not produce their own goods, they had to create their own intangible values, which later were termed services, to fulfill their own needs or those of their family or group members. These early services, which entailed the utilization of the natural resources in their environments, included such activities as food gathering, residence guarding, and raising children. Although all the members of early human societies could have performed these human-made services, the corresponding tasks were usually assigned to different group members based on gender and age. Finally, in their consumption of ecosystem services, people also supplied nature with various services in return, such as the thinning of flora and the transportation of seeds from place to place.

The hunter-gatherer way of life also determined what would later come to be known as the primary sector of the economy (i.e., the collection of raw materials from nature and their processing into products). This virgin economic activity, the extraction and harvesting of nature’s goods from the earth coupled with related services, was based on the value of each good or service. That value, which was associated with the importance of the goods and services to the maintenance of life, was bounded by natural resources and human labor, and entailed minimal use of technology. Moreover, the economic model during that period of human history was based on the collection and use of resources in an efficient process that necessarily let little go to waste. Thus, the hunter-gatherer lifestyle also forged an intuitive connection between people and nature that fostered a harmonic and symbiotic mutual relationship between the two.

Human Revolution

Characterized by the emergence of language, the first big revolution, termed the human revolution or the language revolution, happened around 70,000 years ago, and it also led to the development of consciousness and conscience (Mellars and Stringer, 1989). Though people had already been communicating through voice and gestures for thousands of years, the dawn of language significantly altered the intensity and quality of communication between people, and as a result, they began to gather in larger groups, although they continued to live as wanderers in an economic system based on the hunter-gatherer lifestyle. In addition, these new communication abilities acquired by the human race led first to the worldwide migration of the wise person (i.e., Homo sapiens), who had begun to evolve around 130,000 years ago, and then, around 40,000 years ago, to the appearance of the most developed human subspecies, modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens).

The language revolution changed the social fabric of human life insofar as it allowed humans to share social information, a skill upon which neither their physical lives nor their basic evolutionary drives to survive and reproduce depended. Moreover, group living, which required certain codes of conduct, also raised moral issues that grew out of the need to take the interests of one’s fellow group members into consideration. Though morality is probably as old as humanity, the human revolution added social values to the nascent economic values (i.e., goods and services). Loosely defined as the criteria people use to assess their daily lives, to arrange their priorities, and to choose between alternative courses of action (Friedman and Kahn Jr. 2002), social values provided general guidelines for social conduct, formed an important part of the culture of the society, and accounted for the stability of social order. In addition to its social ramifications, the human revolution also changed the quality and intensity of human-made services, which are in fact based on personal contact, and in the process, people delivered novel services that were not directly associated with the maintenance of physical life. Finally, from an environmental point of view, the human revolution modified the notion of human superiority, and despite their revised perception of their surroundings, people began to feel alienated from nature. Later, the human revolution not only altered the balance between the relative quantities of ecosystem services that humans consumed and services exchanged between people, it also marked the point at which people began to investigate and criticize nature.

Agricultural Revolution

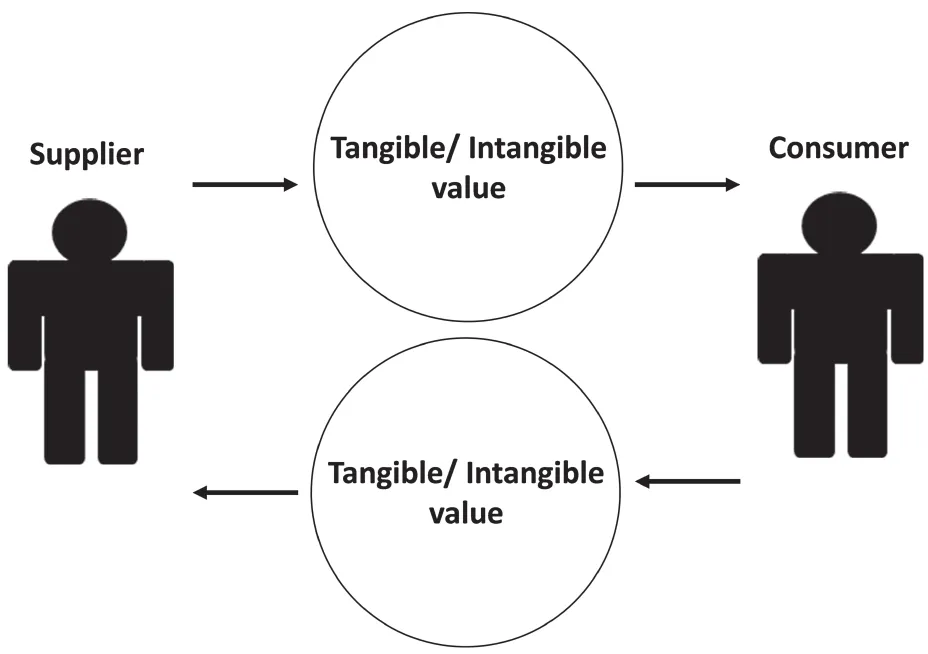

The dynamic relationship between humans and their natural world was inexorably altered by the Neolithic Revolution or the first Agricultural Revolution around 12,000 years ago (Barker 2009). Characterized by the domestication of plants and animals, the agricultural revolution added to the role humans played, from that solely of food consumers to also include the production of food. It changed people’s lifestyle from that of nomadic hunter-gatherers to the more sedentary lives of farmers living in permanent settlements who were able to produce everything for their own needs as well as for those of others. The agricultural revolution also signaled an advance in human-generated services, introducing new services such as storage, sale, trade, and administration, which were usually coupled with the production of goods. This monumental shift in human society also led to a distinction, for the first time, between the production of tangible and intangible values. Thus it effected social and economic changes by expanding the primary sector of the economy from natural-based products to those produced by humans. The relative abundance and variety of food that accompanied the agricultural revolution expanded the meaning of economic-value from the extent to which a good was needed to sustain life to include the utility of the good or its use-value (Gibbins 1976). These changes also led to a crucial transition from an economy that was based mainly on ecosystem provisions to a barter-based paradigm defined by the direct exchange of goods or services for other goods or services and in which everyone is simultaneously a supplier and a consumer. Thus, each value also had an exchange-value representing its trade or market value.

From a social perspective, the prosperity and luxuries afforded by the agricultural revolution together with the greater amounts of free time enjoyed by people encouraged the development of new professions. Yet this new lifestyle also entailed undesirable tradeoffs, for example, it redefined the concept of labor or division of labor. Thus, on an average, agriculturalists performed more work than nomads, on the one hand, but on the other, farming required less cooperation and sharing than hunting and gathering. Some families were therefore able to provide for themselves by farming their own lands or by using laborers or slaves to do that work, and this eventually led to the creation of social classes that, in turn, engendered societal conflict. In addition, despite the abundance and seeming prosperity facilitated by the agricultural revolution, its focus on a sedentary lifestyle supported with domestic crops and animals changed the components of people’s nutrition almost overnight—resulting in a decline in overall levels of health—and also led to drastic changes in the quality and level of daily activity. Moreover, life in permanent settlements exposed people to diseases associated with living amidst one’s own waste and with domestic animals and to a marked increase in the risks of drought, flood, and fire. Finally, although agriculturlism indeed led to prosperity, insofar as it necessitated abandoning a nomadic existence in favor of staying put in settlements, it also created insecurity and increased one’s susceptibility to attack. People responded to the increased threat to their security by accelerating the building of settlements and by creating essential new services such as guarding.

The agricultural revolution also had a significant impact on the natural environment, and paradoxically, the more people turned to farming and experienced a new kind of connection with their natural environment, the farther, in fact, they became from nature. In mimicking nature, people manipulated and exploited it in myriad ways. Indeed, the agricultural revolution marked the first time that humans ruled, or attempted to rule, nature, in the process effectively separating themselves from their natural environment as if they were in control. Inevitably, farming altered the landscape of the world as land was rapidly expropriated from nature while for the first time, distinctions were made between natural and violated areas and between public and private areas. Vast quantities of natural resources were consumed in the process, which also increased soil exhaustion and ultimately disrupted natural selection. The large amounts of water and nutrients required to perpetuate an agriculturally-based society led people to divert natural resources such as rivers. Such engineering feats ultimately had detrimental effects on the environment, which manifested in changes to the natural cycles and balance of local ecosystems that harmed biodiversity along the river’s path and even resulted in some rivers running dry. Finally, the permanent settlements facilitated by the agricultural revolution also caused previously unheard of environmental damage. From the vast quantities of wastewater and waste produced by settlements of people to the massive use of trees to build and heat their dwellings, these phenomena gradually led to the development of new perspectives and philosophies regarding the mutual relationship between nature and humanity. In the latter part of the agricultural revolution, that newfound understanding expressed by some sparked primarily local attempts at environmental protection—from efforts to balance lumber use with the planting of new trees to the formation of nature reserves and animal protection societies—to save and protect what they now understood was their natural heritage (Wiersum 1995).

Although prior to the agricultural revolution all human-made services were produced in conjunction with ecosystem services, later, many services were produced and delivered indirectly (e.g., seeds sowed by people instead of naturally spread or human made water reservoirs). Furthermore, though many services like marketing and storing were still performed in a series, after the goods were produced, many new, standalone services, like administrative and management services, were created for the first time. Finally, in the late stages of the agricultural revolution, the barter economy became more developed, and a value in-exchange economic mode was defined (Humphrey and Hugh-Jones 1992). According to this model, value is produced and delivered by a supplier to a client in exchange for another value, and later on, in exchange for money (Figure 1.2). The roots of a system of commodity money, whose value was based on the commodity from which it was made, for example gold, silver, or tea, date to around 3000 BC in Mesopotamia, while representative money and the use of coins began around 600 BC.

Figure 1.2 Value in-exchange model

The agricultural revolution also marked a period in human history during which the collective knowledge of human society grew tremendously. The subsequent need for management and administrative services to facilitate trade and for the establishment of central authorities constituted what was probably the main driving force behind the emergence of writing, about 4000 years ago, which, in turn, ushered humans from prehistory into the age of written and documented history. Additionally, the final stages of the first agricultural revolution witnessed the birth of monotheistic religions as well as western Greek philosophy and eastern philosophies like Buddhism and Taoism. Both religion, a social-cultural organization under a collection of beliefs, views, norms, and collective rules, and philosophy, the study of fundamental truths and principles of being, knowledge, and conduct, tremendously altered how human beings perceived themselves and their social and natural environments. Moreover, they also prompted people to inquire about the origins of the world and humanity, and to the economic and social values of goods and services, they added the notion of ethical-value, which comprises morals. From the ethical-value perspective, the concept of value also prioritizes goods, services, and actions or behavior according to their importance to individuals or to society, and it is used as a tool that aids decision making about right and wrong or good and bad, ultimately playing a large part in determining our behavior. Finally, the expansion of knowledge and the emergence of religion and philosophy spurred the rise of a variety of new services, such as education, medicine, and entertainment. Previously, these services had been practiced and transferred to some extent within the family mainly to prepare the young with the knowledge and skills necessary to survive, but by the end of the agricultural revolution, they had become integral parts of society.

Finally, both ...